| COMM-ORG Papers | Volume 17, 2011 | http://comm-org.wisc.edu |

Introduction

Part 1: The Structure of the Egyptian Government and Its Sociopolitical Institutions

The 1952 Revolution and Nasser’s Regime

The Rise of the Muslim Brotherhood and Sadat’s Regime

Mubarak’s Regime and the Affirmation of Power: An Analysis and Conclusion

Part 2: The Current Mechanisms and Factors Inhibiting Public Participation in Egypt

The Current Political Constraints Inhibiting Public Participation

The Emergency and Anti-Terrorism Laws

Legislations Governing Political Parties

Legislations Governing NGOs

Legislations Governing Unions

Legislations Governing the Media

The Current Economic Factors Inhibiting Public Participation

Measures And Factors Inhibiting Public Participation In Egypt: Conclusion

Part 3: The Egyptian Education System and Public Participation

The History and Structure of the Egyptian Public Education System

The Impact of the Education Structure on Public Participation

The Impact of Free Education

The Impact of Centralization

The Impact of the National Political and Economic Environment

The Impact of The Education Structure on Public Participation: An Anylsis and Conclusion

The Current Government Initiatives in the Education Field

Current Government Initiatives in The Field of Education: An Anaylsis and Conclusion

Part 4: Conclusion

Caveats and Future Research

Appendix 1- Important Egyptian Constitutional Rights and Freedoms

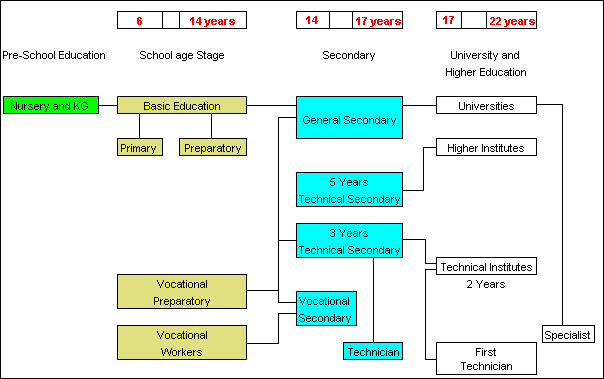

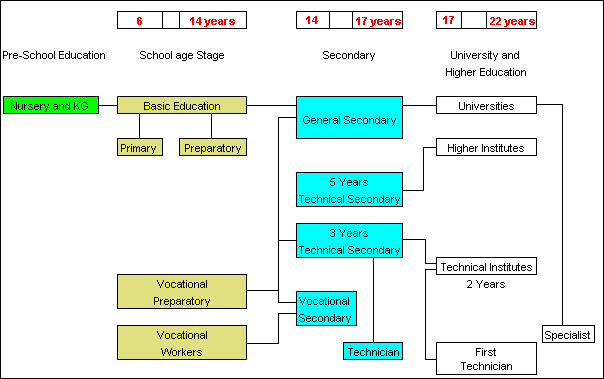

Appendix 2: An Overview of the Egyptian Education System

Appendix 3: Ministry of Education Five Year National Strategic Plan (2007/8 – 2011/12)

References

Notes

About the Author

In 2008, two students died at the age of 10 due to the corporal punishment techniques used in public schools in Egypt (Abdoun, 2008). The two incidents shocked the nation and shed light on the decaying education system in the country. Government and community neglect have bred an education system where the dropout rate is rampant, student achievement is low, and violence is the only utilized means of punishment.

Basic public education in Egypt is free and accessible to everyone under the constitution. However, for many years public education has suffered from inadequate funding and insufficiently trained teachers, resulting in devastating consequences for the country's children.

There is a chronic shortage of school buildings, desks, and teaching materials. In fact, according to United Nations Children’s Fund (UNCIEF) report, more than half of the 25,000 schools that were operating in the country in 2003 were considered unfit for educational activity and were a threat to the physical well-being of children and teachers.

Teachers are underpaid and poorly qualified. The teaching techniques practiced at public schools have not been updated since the 1950s. The typical teaching practices at Egyptian public schools emphasize rote learning and memorization, rather than explanation, reasoning, and problem-solving. Corporal techniques have become more violent and aggressive, but more importantly they have become the norm in everyday school life.

Meanwhile, parents view schools as uninviting governmental buildings. They view education as a service that is provided by the state and they do not see a role for themselves in the functioning of the school. There are many constraints related to the sociopolitical environment of the country that inhibit parents from taking an active role in their children’s education process. An important element is that there are no legitimate channels that allow the parents to express their concerns and grievances at local or national levels. Consequently, the parents have become more accustomed to the deteriorating schooling system and infrastructure, and low quality education.

Certainly, in the political and social spheres, volunteerism and activism are limited in Egypt due to the various control mechanisms, imposed by the current regime, on activities of opposition parties, elections, non-governmental organizations, unions, and the press. Essentially, the current structure does not allow for a channel where the public can express its concerns and contribute to the decision-making process. This sociopolitical structure does not provide a space in society where people can come together to debate, associate and seek to influence their government and to change their own living reality. Ultimately, many citizens refrain from participating in the decision-making process altogether, which in turn, this thesis argues, results in the deterioration of public service, as witnessed in the education field.

The low voter turnout of the presidential election of September 2005 further illustrates how the public is disengaged from the government’s decisions and is unwilling to participate. In February 2005, President Hosni Mubarak modified the constitution to allow Egypt’s first multi-candidate presidential elections1, where he claimed 88% of the votes (Freedom House, 2007). The reforms were considered a very important milestone in the Egyptian democratization process. However, the elections were characterized by a voter turnout of less than 25% of registered voters. Since the repressive behavior of the government does not give any assurance that public opinion will be reflected in the decision-making process, many individuals did not believe that the reforms were a genuine attempt by the government to democratize the political environment. Thus, many Egyptians did not show to cast their ballots and refrained from participating.

Sadly, Egyptian citizens’ perception of the government and “reform” was proven to be correct in the September 2005 presidential election. The election was highly manipulated by the government. The government interfered in the voting process through vote buying and voter coercion. Independent monitors, prosecutors, and the Egyptian Judges’ Syndicate all blew the whistle on government electoral misconduct (“Not yet a democracy,” 2005).

However, it is important to recognize that the current regime – despite its repressive behavior – has expressed a real desire to encourage public participation and community involvement, particularly in the education field. Recently, the government has passed two important initiatives, Board of Trustees and National Standards, designed to provide a venue for parents, stakeholders, and community members to express their concerns and to influence the education process at the school level. The two initiatives are considered a breakthrough, considering that the government has had limited public participation in social and political sphere for more than 50 years. The government for the first time is acknowledging the importance of community participation as a significant parameter to improve the quality of education in Egypt.

The puzzle that this research attempts to resolve is that given the current hierarchal structure of the sociopolitical institutions in Egypt and the repressive behavior of the regime, why currently is the government fostering public participation in the education field?

In this respect, this study will examine the history, the developments, and the political values that shape the Egyptian government and the sociopolitical institutions of the country. This part of the study will also analyze how the military ethos and leadership shaped sociopolitical institutions that are unresponsive to the public’s demands and needs, contributing to the current public apathy. Then in turn, the study will delineate where in Egyptian legislation and the economic structure this indifference to popular will is institutionalized. The third part will attempt to understand the reasons behind the current government initiatives that aim at encouraging public participation in the public school education field. This part will also analyze the education system and problems to illustrate how the absence of public participation in the government decision-making process has had a dire impact on public services2 and impairs the country’s development. The paper will conclude by arguing that these impacts can be reversed, that a democratic political environment can in turn foster public participation at the local level and begin to achieve social parity in Egyptian society.

It is important to note that given Egypt’s Pharaonic past and Islamic heritage, a possible psychological readiness of Egyptians to accept authoritarian rule facilitates the persistence of authoritarianism in this country. This paper will not address the cultural factors that contribute to the lack of activism and volunteerism in the Egyptian society. Nonetheless, even though the liberalization of the sociopolitical institutions and environment in Egypt will not immediately prompt a culture of civic engagement, still, this paper argues, it will actively foster the proper environment that could lessen the effect of these cultural traits and begin to spur public participation.

Egyptian political and institutional structure today is largely influenced by the political values of the 1952 Revolution. Studying the role of the 1952 Revolution in shaping the political context of Egypt today can provide insight into why volunteerism and activism is limited. It is also useful to study the historical development of Egypt’s politics to identify the key patterns and actors that shaped the political process and social institutions in modern Egypt. This chapter will pinpoint the crucial role that the military and its leadership played in shaping the sociopolitical sphere in Egypt through addressing social and political problems using a military mindset.

The purpose of this chapter is to delineate the historical development of Egyptian political values in order to explain its modern political, social, and economic structure. This chapter will also detail how the regime’s military campaign against Islamist militants led to the sacrifice of political liberties, diminishing public participation altogether.

The premise underlying this chapter is that the military ethos of the 1952 Revolution is still dominating the sociopolitical sphere and determining the political and social process of the government today, contributing to the current public apathy.

In 1952, Colonel Abd el Nasser and group of military leaders known as the Free Officers staged a coup d’état in Egypt, which abolished the monarchy. The following year, the group established the Republic of Egypt, installing Nasser as president and pursuing a political agenda that promoted Arab nationalism and socialism. The 1952 Revolution has drawn massive support by all citizens.

According to Ziad Munson’s political opportunities structure theory (2001), which focuses on the sociopolitical context from which social movement and group mobilization can occur, attributes the success of the 1952 Revolution to the sociopolitical problems in Egypt prior to 1952. Munson argues that domestic unrest over the British occupation3 and its domination of the Egyptian political sphere; the weakness of Egyptian political parties at the time; the defeat of Egypt in the 1948-1949 Arab-Israeli war; and the growing gap between rich and poor, constituted the main factors that have contributed to the success of the 1952 Revolution. Essentially, the Revolution promised to end feudalism, imperialism, and capitalist influence on government, meanwhile establishing social equality, democracy, and a strong army.

During the early years of the Republic, the government faced enormous pressures, externally and internally, that jeopardized its stability and its legitimacy. The first pressure was imposed by the British force, which supported the monarchy and planned to overturn the new regime. However, the internal weakness of the British government at the time prevented Britain from overthrowing the new Egyptian government.

The 1952 Revolution government was also threatened by the growing strength of the Muslim Brotherhood4, the Islamist faction that calls for the establishment of an Islamic state based on Islamic teachings and ideologies. The group was able to rise into power due to the sociopolitical problems that occurred prior to 1952. The Muslim Brotherhood increased its strength following the establishment of the Egyptian state and attracted mass public support. The Islamist group particularly gained the support of the best-educated groups in Egypt; the members of the organization were composed of engineers, doctors, and students5.

The group’s Islamic agenda and strong mass public support imposed a critical threat on Nasser’s and the new government’s socialist political agenda that promoted self-determination and Arab unity. In an attempt to respond to critical threats of national security, the government relied on the military to suppress the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood. In 1954, the Muslim Brotherhood was banned as a legitimate political party. Through the use of military force, the government crushed the Muslim Brotherhood by imprisoning many of its members and exiling all opposed to the new government.

Even though the new government employed the language of “social justice,” ironically military force and hierarchical structure was thought to be the only method that could bring the country to order and achieve “social” as opposed to “political” democracy. To maintain and ensure government domination over sociopolitical sphere, it established social institutions and a government structure that reflected a preference for order and an aversion to instability (Huntington, 1968; and Perlmutter 1977; Feaver, 2003). Essentially, the 1952 Revolution formed the new state and its social and political institutions on the fundamentals of institutional model theory of government, where public policy is authoritatively determined, implemented, and enforced by government’s institutions such as the parliament, courts, bureaucracies and so on (Dye, 1976; and UNDP Program on Governance in the Arab Region, 2008). This institutional structure was believed to maintain order and status quo by establishing hierarchical organizational that would not respond to change, corresponding to military organization.

The outcome of this military intervention and pro-socialist agenda led to the creation of a repressive police state that favored a centralized economic, social and welfare regime in Egypt. The army and its leadership were engaged in politics and viewed themselves indispensable to the regime and the state, restricting the participation of any organization or individuals. In the name of national security and prosperity, Nasser’s regime and the government of the 1952 Revolution established highly centralized and authoritarian bureaucracy in which all political parties and civil society organizations were banned. As a result, the Egyptian government, supported by the military, was independent of civilian will and rule and had isolated citizens from the decision-making process.

In spite of the repressive behavior of the state, many citizens continued to support the government for several reasons. First, Nasser was considered a national hero who had brought independence to Egypt from the British control. The nationalization of the Suez Canal6, which was under the control of the British government for more than 90 years, bolstered his image as a national hero even further. “Also, a Czech arms deal and a close ties with the Soviet Union, as contradicted the interest of the Western alliance, further contributed to Nasser’s reputation as a Pan-Arab hero who stood against the imperial domination of the Western powers” (Murat, 2007).

Second, the government was very successful in imposing the military ethos on the country and solidifying it in the mind of many Egyptians through controlling and using media outlets, most notably articles published in Al Nasr, Al Difa’ (Defense), and El Qwat el Maslaha (the armed forces) magazines, which represented the view of the military and its leadership. These magazines devoted many of its pages to political, economic, and social issues, usually from the standpoint of military discipline. Other articles had a special focus on the contribution of the military to the Egyptian society. For example, Al Nasr magazine has emphasized the role of the military in the economy with articles under the titles of “The Battle of Building and Construction” (NO. 492) and “The armed forces in battle of development” (NO. 497). These articles had given the opportunity to the military to promote its contribution in the infrastructure of the country and its role in protecting it. The establishment of military’s Center of Strategic Studies (1986), an armed forces think tank, has further legitimized the role of the Egyptian military in all spheres (Campbell, 2009).

Even after the overtly military aspect of the regime after 1952, however, military-supported authoritarians remained in power and the sociopolitical institutions of the country have continued to be rigid, centralized, and unresponsive to change. Through controlling and using media outlets in disseminating military ethos in the country, the regime was able to justify the absence of democratic control on the basis of national security. Consequently, this regime structure alienated the public from decision-making process on the political and social level. This era ended with the death of Nasser in 1971 and the occupation of Sinai Peninsula under the Israeli forces.

After the death of Nasser, Anwar Sadat, senior military member of the Free Officers, assumed the presidency. Sadat sought a change in direction from Nasserist socialism. Essentially, Sadat’s presidency committed itself at achieving economic liberalization and regaining the Sinai Peninsula7 from Israeli. The new Egyptian president viewed the West, particularly the United States, as a key political alliance that was needed to support his economic liberalization policies (referred to as Infitah policies in Arabic literature) as well as to pressure Israel to return the Sinai Peninsula (Campbell, 2009; Niblock, 1993; and Hinnebusch, 2001a).

Under Sadat’s regime, Egypt experienced a very short era of political liberalization; according to Freedom House in 1976-1978 Egypt’s score in liberalization8 improved significantly, from “not free” to “partially free.” Sadat was able to contain the military rule and its leadership to its original function through eradicating the military leadership’s control over social and political institutions. This movement is referred to as “Corrective Revolution,” where Sadat legitimized the use of force to remove military leadership from the social and political sphere. He also removed all leadership that supported socialist and Nasserist ideology.

Terms such as a “modern state” and a “new” and “free” society, “state institutions,” “lasting constitution” and the “rule of law” were introduced to the Egyptian society (Campbell, 2009). However, the liberalization process was overshadowed by the rise of domestic unrest over Sadat’s peace agreement with Israel9 and the dire economic conditions of the country. Sadat’s strategy of peace with Israel, which he believed was necessary to improve Egypt’s economic conditions, was not welcomed by many Egyptians. The Egyptian community at that time viewed Israel as the aggressor and invader that had led to the loss of many of Egyptian lives. The Egyptian peace with Israel also strained the Egyptian-Arab relationship. Many countries in the Middle East viewed the treaty as a betrayal from the Egyptian side to the Palestinian self-determination cause. As a result, Egypt was isolated from its neighbors. The failure of Sadat’s economic liberalization-Infatah policies-which failed to attract foreign investments to Egypt, constituted yet another source of discontent.

The rise of domestic unrest and regional pressures created a favorable environment for the Muslim Brotherhood10 to resurface (Munson, 2001). The organization gained strength as a strong political force in the country in the late 1970s. Upon its return, the Muslim Brotherhood established a political party and carried out public campaigns, calling for the restoration of Islamic Law as the solution to the problems facing Egypt (Mutra, 2007).

The rise of the Muslim Brotherhood had once again imposed an internal threat to the government, jeopardizing the legitimacy of its policies. Still influenced by military ethos of the 1952 Revolution, Sadat reversed the liberalization process and tightened the political system in the late 1970s. He rearranged the sociopolitical institutions to reflect top-down hierarchy to maintain the government control and to maintain the status quo. The focus of political liberalization came to a complete stop after the assassination of Sadat by a member of the Islamist Jihad.

The Sadat era was cut short by his assassination in October 1981. Sadat was succeeded by Vice President Hosni Mubarak, formerly the air force chief of staff. Mubarak represented continuity in the line of ex-military officers holding executive office. Mubarak’s political agenda focused on promoting economic growth. However, at the beginning of its rule, Mubarak’s government faced enormous threat from the growing Islamic force inherited from Sadat’s regime.

By the late 1980s, the Muslim Brotherhood constituted the most powerful opposition in the country holding 25% of the parliament seat, 36 seats. As a result in 1987, other political parties sought an alliance by “Islamizing” their agendas. That year the Muslim Brotherhood united with the Labor and Liberal parties under the “Islamic Alliance” (Hafez and Wiktorowicz, 2004). Through its effective campaign and alliances, by the late 1980s, the Muslim Brotherhood was on its way to becoming an alternative to the state. The Muslim Brotherhood also used its influence to criticize Mubarak’s regime. The government in return revoked the Muslim Brotherhood status as a legitimate political party.

However, the government action did not isolate the Muslim Brotherhood; it has in return increased its influence and its threat on the government and the society. As a response to the government isolation, Islamic activist sought direct conformation with the government to overthrow it (Cleveland, 2004). By the 1990s, Islamic violence increased dramatically through bombing in public places, assassination, and ambushes. There were 741 incidents of Islamic violence between 1992 and 1997, compared with 143 incidents between 1970 and 1991 (Hafez and Wiktorowicz, 2004).

Accordingly, the government once again used its military mindset to respond to Islamic violence, imprisoning all opposing to the government and restricting the participation of any individual or organizations in the decision-making process. The military behavior of the state explains why the economic reforms liberalization in the 1990s did not result in political democratization. Mubarak’s presidency firmly established one-party and one-man rule, eliminating all opposition and ensuring that all sociopolitical institutions in the country were under the control of the government. In return, Mubarak’s government reconfirmed and legitimized the centralized sociopolitical institutions of the 1952 Revolution to ensure that the government had a monopoly over all decisions in the social and political sphere.

Following the attacks of September 11 and the invasion of Iraq in 2003, however, opposition to Mubarak’s regime intensified outcry for political change. The excessive power of the government and growing reliance on the United States for financial aid called the country’s sovereignty into question; not only by the Muslim Brotherhood, but other opposing organizations such as Kaifia- a liberal opposition group calling for the removal of Mubarak from office.

Opposition forces composed of all factions – liberal, leftist, and the Muslim Brotherhood – demanded multi-candidate presidential elections, the suspension of emergency law, full judicial supervision of elections, and the suspension of limitations on the creation of political parties, and an end to government involvement with the activities of nongovernmental organizations.

In 2005, constitutional reforms allowed for the first multi-candidate presidential election, where Mubarak claimed 88% of the total votes. During the same year, Muslim Brotherhood, whose candidates ran independently with no party affiliation, claimed approximately 22% of parliament seats. However, the opposition failed to carry out the rest of their demands due to their internal and organizational weakness (Murta, 2007). More importantly, the oppositions were not able to advance their agenda due to the highly constricted political and economic environment of the country that limits all efforts that aim to change the status quo and the government.

Today, the persistence of authoritarianism in Egypt constitutes the main factor behind the absence of public participation. There are two general views presented by scholars on the persistence of authoritarianism in the Middle East. The first view, presented by Farhad Kazemi and Augustus Norton, attributes authoritarianism to state behavior. The second view, presented by Oliver Schlumberger, Frederic Volpi and Steven Fish, suggests that it is the hierarchically shaped sociopolitical structure11 and sociopolitical patterns of interaction that promote authoritarianism in the Middle East region. In the case of Egypt, the two views collapse together, since the military ethos and its leadership is governing the state.

The preview of Egyptian history showcases the relevance of both claims. Since the 1952 Revolution, the government has been guided by military principles. By using the military mindset, the government has isolated not only the Muslim Brotherhood, but all movements or individuals seeking the establishment of grassroots movement at the political and social levels. Therefore, as argued by Norton and Kazemi (1999), the government behavior since the 1950s has contributed to the persistence of authoritarianism in Egypt. Essentially, the military-inspired Egyptian government since the 1950s has successfully secured and protected its control over the government by adopting several practices and legislation that are likely to sacrifice civil and political freedoms in the name of national security. Certainly, the behavior of the Egyptian government to maintain its control over the government and the reign using military ethos constitutes the main factor behind the absence of public participation and the persistence of authoritarianism in Egypt.

Furthermore, in the 1950s the government created highly centralized sociopolitical institutions that reflect a preference for order and an aversion to instability. This institutional structure is believed to maintain order and the status quo by establishing hierarchical organizations that would not respond to change, resembling the military institution. This factor confirms the argument by Schlumberger, Volpi, and Fish that the hierarchical shaped sociopolitical institutions tend to make the sociopolitical environment an unsuitable place for a truly democratic civil society to develop. Therefore, the Egyptian military inspired sociopolitical structure constitutes yet another main factor that limits public participation and contributes to the persistence of authoritarianism in the country12.

Unfortunately, the absence of public participation and the persistence of authoritarianism have led to a growing Islamic violence and deteriorating public services. This military mindset of the government that legitimizes the use of force and the repression of civil liberties adopted by the Egyptian government since the 1950s has bred ground for Islamic violence to grow. In support of this view are Muhammed M. Hafez and Quintan Wiktorowicz (2004), who call attention to the political opportunity structure in relation to regime repression. In their analysis, Hafez and Wiktorowicz point out that the growing Islamic violence coincides with the political de-liberalization of the 1990s, evident in the high number of causalities and injuries resulting from Islamic violence during this period. The study compared the casualties of 1,442 deaths and 1,773 injuries from 1992 to 1997 to the casualty rate of 120 deaths that took place from 1970 to 1981. Accordingly, the study argues that the de-liberalization of the 1990s is likely to account for the growth of Islamic activism through bombings, assassinations and ambushes that took place in the same period. This study correctly concludes that the existing constraints within Egyptian politics, the limited accessibility of the political system, and the high degree of state repression are key factors in the increase of Islamic violence.

Moreover, the current military-inspired sociopolitical institutions have led to the deterioration of public services in the country, as this centralized and controlled sociopolitical structure, which has weakened local governments, bred corruption in all levels of government, and contributed to the current public apathy.

Local governments in Egypt have virtually no power in making any decisions regarding their activities. All policies and budgets are determined centrally with no adequate participation from local government officials, non-governmental institutions, or the public, thereby allowing for greater corruption, increasing the scope of arbitrary central government decisions, decreasing bureaucratic performance, and developing a high level of uncertainty.

This structure limits public participation, and it does not give any assurance that the public opinion would be reflected in the decision-making process (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2004). As a result, the public perceives the government to be distant and unaccountable. Many individuals in Egypt distrust both the process and the outcomes of decision-making. Ultimately, many citizens refrain from participating in the decision-making process altogether.

Furthermore, Egypt’s government system, in line with military ethos, has continuously commanded the loyalty of its citizens “to enact policies governing the whole society and to monopolize the legitimate use of force that encourages individuals and groups to work for enactment of their preference into policy” (Dye, 1976). The concept of citizens' loyalty to the state and centralized decision-making has played an evident role in deterring the public from taking an active role in the decision-making process in any spectrum.

The notion of commanding citizens' loyalty and legitimizing the use of power to implement national policies has alienated the middle class from participating in public life. Many intellectual elites and middle-class citizens have preferred not to participate in public life to spare themselves the risk of being imprisoned or ridiculed by the government (Abdel Halim, 2005).

Since there are no measures at the local level that ensure voter accountability and limit the elected official's violation of public property, corruption has become widespread in Egypt at all levels of government. Egypt ranks 105th out of 179 most corrupt governments in the world according to the Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index for 2007. Bribery of low-level civil servants is part of daily life, and there are allegations of significant corruption among high-level officials (Index of Economic Freedom, 2009). In 2006, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) noted the need to address corruption so that good governance values could be fostered and the public could once again trust the government and participate actively in its community.

Therefore, it is important to note that the greatest obstacles that hinder greater civic engagement in Egypt are the authoritarian behavior of the state and highly centralized government structure13.

The absence of public participation has had a dire impact on public services in Egypt, particularly in the education system. Currently, the public school system in Egypt suffers from poor overall quality. Its infrastructure is deteriorating; corporal punishment is widespread; the dropout rate is increasing; and unemployment among school graduates is pervasive

The education system, its history and its current problems, is an important case that illustrates how the military mindset of the 1952 Revolution shaped the nature of social institutions in Egypt. Public school education deteriorated under militaristic rule, as over time the education system had widened the inequality gap and restrains household income. The current education system is depriving the poor and middle class of quality education, which in turn limits their employment opportunity. The wealthy, of course, are in a better position, as they can afford private schooling for quality education. These impacts will be discussed in part three of this paper.

Today, the Egyptian sociopolitical sphere refers to an arena where repression, rather than democratization, takes place. Hosni Mubarak’s one-man, one-party rule has been dominating the political atmosphere since 1981. The regime is continuously suppressing all opposition either through the use of force or through undermining any prospects for democratic political practices in Egypt. Due to the regime's authoritarian behavior, public participation has been completely suppressed. Certainly, the current Egyptian sociopolitical environment is a great barrier to any organization or individual seeking to promote a grassroots reform process.

This section will delineate the various political and economic factors that inhibit civic engagement in Egypt14. This section will also illustrate how the legislative framework, shaped by government imposed repression, constitute the main factor limiting public participation in Egypt today. Understanding the Egyptian legislative framework and the economic situation of the country will help this study identify the areas of intervention and policy measures that are required to spur public participation.

Mubarak’s regime is continuously legitimizing various control measures on activities of political parties, elections, civil society organizations and the press. No organization is free of government surveillance. This section will outline the legislation that are currently in place and is limiting the ability of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), political parties, unions, and the media from functioning effectively in mobilizing the public, raising public awareness on important public matters, and seeking the establishment of a grassroots movement in any public issue.

The Emergency and Anti-Terrorism Laws

The Emergency and Anti-Terrorism Laws constitute the greatest obstacles to public participation in Egypt. Both laws preclude many basic human rights provided by the constitution; their provisions allow for citizens to be arrested without charges, restrict freedom of assembly and speech, allow unwarranted home search, and disregard privacy and security of communication.

Except for a period of five months under Anwar Sadat’s rule, Egypt has been under a “state of emergency” since 1967, which in practice has led to indefinite detentions without trial and the banning of demonstrations. The Emergency Law gives the executive branch the power to suspend all judicial and constitutional orders to protect the country from any national security threats (UNDP Program on Governance in the Arab Region, 2008).

Mubarak’s regime extended the Emergency Law to 2010. The government requested the extension of the law based on the need to confront the terrorist danger that threatens Egypt's security (UNDP Program on Governance in the Arab Region, 2008). In reality, however, the Emergency Law enables Mubarak’s regime to exercise firm control over Egyptian politics. Therefore, the regime extended the Emergency Law as a response to the prominent representation of the Muslim Brotherhood in the 2005 parliamentary elections (Freedom House, 2006).

Mubarak’s regime used the Emergency Law to suppress the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood in the1995 parliamentary elections. The regime conducted a series of arrests, targeting representatives of the Muslim Brotherhood, aiming to neutralize the opposition. As a consequence, days before the elections, fifty-four members of the Muslim Brotherhood were sentenced to prison. The 1995 parliamentary elections resulted in the ruling party’s victory that won 94% of the seats (Hafez & Wiktorowicz, 2004).

More recently, the regime used the Emergency Law during the 2005 parliamentary elections, where the government targeted many Muslim Brotherhood sympathizers by security forces and prevented them from casting their ballots in some opposition strongholds (Freedom House, 2006). In the aftermath of the parliamentary elections, the Muslim Brotherhood, whose candidates ran independently, managed to win 22% of parliament seats, while the ruling party took the lead by winning 78% of the parliament seats.

In 2007, Mubarak’s regime was able to amend many elements of the Emergency Law in the constitution (UNDP Program on Governance in the Arab Region, 2008). The amendments are referred to as the Anti-Terrorism Law. The Anti-Terrorism Law gives the government the authority to preclude three constitutional rights in order to ensure the government’s effort at combating domestic terrorism: Article 44 (protection of home from unwarranted searches), Article 45 (privacy and security of communications), and Article 41 (freedom from arbitrary arrest or detention) (Denis & Kimberly, 2007; Egyptian Constitution, 2007). The Anti-Terrorism Law represents the “most serious undermining of human rights safeguards in Egypt, since the state of emergency was re-imposed in 1981” (Amnesty International Report, 2007).

Even though Egypt does not have a recognized Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the rights of individuals and other minorities are enshrined and granted in the Egyptian Constitution (See Appendix 1 for more details on the Egyptian Constitution Rights and Freedoms). All these rights, however, are effectively suspended under the Anti-Terrorism and Emergency Laws.

Legislation Governing Political Parties

Theoretically, Egypt is a multiparty political system (Egyptian Constitution 2007, Article 5). In practice, Egypt is one party system. The ruling party, National Democratic Party (NDP), dominates the parliament and the executive branch. NDP hinders the efforts of other parties to take control (Abdel Halim, 2005).

There are approximately 24 parties legally registered, while several others have had their registration applications consistently denied, particularly the underground Muslim Brotherhood party15 (Denis & Kimberly, 2007).

The legislative framework isolates political parties from any social grassroots movements. The Egyptian law prohibits the establishment of political parties grounded in social and professional movements. Therefore, the existing legislative framework weakens political parties’ ability to identify with citizens, by removing partisan politics away from unions, grassroots organizations, and other associations. Associating with social grassroots movement is a prerequisite for creating a strong political environment and strong multiparty structure. Through this interaction the public can move its concerns to the political arena and ensure that its demands are reflected in the decision-making process.

“Many of the major political parties in democracies or emerging democracies were begotten by syndicates, the most well known examples of which are the British Labor Party or Poland’s Solidarity movement” (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2008). Thus, the law misrepresents the proper role of political parties and exposes the whole democratization process to tensions by triggering official barriers to political parties’ activities.

Egypt has a vibrant civil society consisting of 16,000 registered not-for-profit and international organizations (Abdel Halim, 2005). Nevertheless, NGOs in Egypt are limited in terms of their activities and their scope. Since 1950s, the government has frozen civil societies’ activities on the basis of national security.

“Historically, the 1952 Revolution alienated both the private and the civil society organization sector, openly or implicitly by claiming to represent all of society, provide universal welfare services and subsidies on most goods and services, free education, as well as employment for all graduates, in return for national allegiance and support” (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2008).

Today, present legislation still places barriers on the ability of some NGOs to freely associate and act in consequence. The NGO law grants the state the right to expose civil right organizations to criminal penalties, including imprisonment, fines, and the involuntary dissolution of the association, in the case of any direct violation.

Many activities that are prohibited under the law are not clearly defined; it frequently uses terminology that is open to interpretation. This includes terms such as “the public order,” “public ethics,” “decorum,” and “threat to national unity” (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report; and UNDP Program on Governance in the Arab Region, 2008). This leaves the government the discretion to determine whether a violation has occurred or not.

The authorities have used this undefined terminology in the law to politicize human rights and the rights of minorities, and it has also arrested activists advocating for social justice. For example, three female activists were arrested in May 2006 during a peaceful demonstration for greater political participation of women. By equating women’s rights issues with political activities, government authorities have justified canceling NGO awareness raising activities such as a 2006 multi-NGO Women’s Day Celebration (UNDP Program on Governance in the Arab Region, 2008).

Human rights organizations are a primary target of Mubarak’s regime. The government confronts human rights organization because such organizations through their activities expose the regime’s human rights violations. In its effort to maintain legitimacy, the Egyptian government labels human rights organizations as threats to national security that aim to tarnish the country’s international reputation. Since the mid-1980s, Mubarak’s regime has accused such organizations and human rights activists of treason for opening the gate to foreigners to intervene with Egypt’s affairs. In the name of protecting Egypt’s national interest and sovereignty, the government has imprisoned many human rights advocates. Because the NGO Law does not define the activities that constitute a threat to national security, the authority could imprison any human right advocates.

Other provisions of the NGO Law give excessive discretion to the executive branch over key administrative and financial decisions that impede civil society organizations. The government can directly deny the registration of some organizations on the basis of national security (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2008; and UNDP Program on Governance in the Arab Region, 2008). The executive branch has exclusive authority to control civil society organizations’ management of finance. For example, permission from the government is required for the receipt of all funding from foreign and domestic sources (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2008; and UNDP Program on Governance in the Arab Region, 2008).

The excessive power of the regulatory authority, the ambiguities in the law, and Emergency law and Anti-Terrorist law are impeding “the civil society organizations’ ability to conduct their affairs successfully, earn credibility, participate successfully in networking, and scaling up activities” (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2008; and UNDP Program on Governance in the Arab Region, 2008). These non-democratic practices limit the ability of civil society organizations to be effective, and discourage citizen participation altogether.

There are two types of unions in Egypt. The first type of union is comprised of members that are obligated to join as a condition for practicing a certain profession. An example for that is the Physicians Association, which includes all licensed doctors. The second type of syndicate is comprised of members recruited on a voluntary basis and membership is not a prerequisite for practicing the profession such as Syndicate of Journalists (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2008).

Membership in Egyptian unions is low and the participation of members in the affairs of their unions is limited (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2008). The weakness of unions in Egypt is a result of several factors, the first of which is low citizen participation, since most Egyptian unions are not founded on voluntary or selective membership. Second, the structure of unions in Egypt creates a number of problems, as the Egyptian government assigns to unions certain functions such as licenses to practice a certain profession, as well as the supervisory role as regards these professions. Therefore, Egyptian unions work on implementing state-dictated policies, rather than promoting professions and members’ interests. Third, the legal frameworks governing these groups are very strict, impeding unions’ ability to promote their members’ interest. By the virtue of the law, the government oversees all unions’ activities. The state supervision goes as far as the delegation to appoint cadres, or leadership of unions16.

The existing legislative framework limits the channels by which members can move their concerns from unions to political parties. Internationally, most unions’ members transfer their concerns from the civil to the political arena by cooperating with political parties. However, Egyptian law prohibits unions from establishing any ties with political parties (Law 40 of 1977). Even though unions have a duty to interact with political parties, if this stems from the need to defend professional or group interests.

Based on the restriction laws, public party gatherings and marches are prohibited. During the 1995 election campaign from November 1995 to December 1996, 1,392 Islamist campaign workers and supporters were arrested by Mubarak’s regime for violating the restriction order (Dillman, 2000).

Technically, the law gives workers the right to strike, but only if approved by the leadership of the executive branch. Thus, workers cannot strike without the consent of the government. In spite of the law, the independent Egyptian newspaper el Masry el youm has reported an estimate of 222 workers strikes during 2006 alone, all of which were illegal.

The workers’ demands are increasing everyday in Egypt. Unfortunately, the current legislative framework does not provide the necessary space for the public in general to express their concerns. Public demands are inevitable; the question arises as to whether the state has the political will or the inclination to create a model for unions that would allow the recognition that these associations are there to express group interests.

Legislation Governing the Media

Egypt’s media is very diverse. Even though privately owned media outlets have been increasing in Egypt during the last decade, the government still owns and controls the largest written, audio, and visual media. The editors of the three daily leading newspapers are appointed by Mubarak. The government also regulates the privately owned media outlets. Freedom of speech is safeguarded in Egyptian constitution and its legal framework. Despite the constitutional guarantee, however, restrictive media laws are in place and an assortment of press offenses are criminalized.

Laws and practices that regulate the exercise of freedom of association, freedom of expression and freedom to obtain information represent constraints on media. Press legislation passed in 2006 enumerated thirty-five media offenses punishable by prison sentences (Denis & Kimberly, 2007). Media personnel can be under risk of prison if they insult public figures or bodies, spread rumors aimed at instigating terror, and harm the public welfare (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2008). However, these laws are not clearly defined and they are open to some interpretation.

The executive branch uses the law’s vague terminology to suppress voices critical of government. For example, Ibrahim Eissa, editor of the largest opposition newspaper Daily el Destour was arrested earlier this year for allegedly spreading “dangerous” rumors about the health of President Mubarak. The authority saw this particular article as an opportunity to arrest Eissa, who have been very critical of the government behavior in recent years. He was arrested on charges of broadcasting false stories, disrupting the peace, and harming the national security. Because the media law does not define the activities that constitute a threat to national security, the authority could arrest Eissa or any other journalist.

Moreover, journalists can not access government documents, as currently there is no Right of Information Law in Egypt. Therefore, the government controls the dissemination of information, limiting journalist as well as civil society organizations’ ability to monitor government’s activities (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2008).

Written media and the internet enjoy relatively larger freedom in speech in comparison to other media17, as state-owned, semi-official, and opposition periodicals are distributed daily, weekly, and monthly. The effect of print media is, of course, limited by the fact that a large sector of Egyptian society is illiterate, 23% of the population, which constitutes 17 million (Abdel Halim, 2005; and Stockholm Challenge, 2008). This in turn reflects on citizen political awareness, and hinders the awareness of the importance of political participation. The affect of the internet is limited as well as the number of households owning a computer and have access to the internet is only 6 million- the population of Egypt is 72 million (Stockholm Challenge, 2008).

Egypt’s economy during the 1950s and 1960s was guided by socialist principles, where the government took the responsibility for providing economic and social relief for all citizens. Many economists blame this period of time for Egypt’s economic deterioration. Egypt's economy improved dramatically in the 1990s as a result of several arrangements with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the move by several, mainly Arab, countries to relieve a large portion of its debts (National Encyclopedia, 2008). There have been massive macroeconomic reforms in 1980s and 1990s, which have transformed the government’s economic and social structure and have helped the private sectors in achieving a higher share in the economy.

The private sector in Egypt enjoys more public participation rights than any other social group, as the government believes that the private sector would generate the resources needed to continue universal welfare benefits (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2009). “This sector was given new rights to organize and lobby to advance its own interests (chambers of commerce, businessmen’s clubs). This opening up provided more space for non-state actors and allowed an increasing number of groups to voice their demands” (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2008).

Unfortunately, the government was unsuccessful in adopting new social policies that would match the liberalization of the economic regime. To achieve economic progress, the government has made strides in instituting liberal, market-oriented economic reforms, but laws did not change to allow explicitly more freedoms for the public and civil society institutions (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2008). Thus, economic reform is increasingly perceived by the middle and lower ranks of the vast salaried state bureaucracy, the working class, and labor unions to work against their interests, since their access to better wages and upward mobility was not enhanced (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2008).

However, Egypt’s policies and political institutions will not be acceptable to its citizen as the economy continue to grow. As individuals enjoy higher income due to economic growth, citizens’ demand accompanying an increased standard of living will also increase. Individual demands for a better infrastructure and personal freedom will ultimately force the government toward opening its social and political institutions (Friedman, 2007).

The fact that we have not seen Egypt opening up its political and social institutions does not imply that the relationship between rising income and personal freedom does not exist. The reason that Egypt has not yet reached this stage is because the per capita income in Egypt has grown from a very low level. Despite the overall growth in the country’s GDP of 7.1%, poverty and illiteracy in Egypt limits public participation to a greater extended (CIA the World Factbook, 2007).

Egypt’s standard of living today is still only a small fraction of that in highly developed Western democracies (Friedman, 2007). Illiteracy is still a major problem; 25% of the population is illiterate, despite the government and international organizations efforts in the past two decades to reduce it (Stockholm Challenge, 2008). The poor and the illiterate are disadvantaged in securing equitable representation in the decision-making process.

Egypt’s political environment in itself is a great barrier to any organization or individual seeking to promote a grassroots reform process. Preconditions for political participation are not provided, and if they are provided, they are not exercised by Egyptian citizens. As discussed above, the legislative framework places various control measures on activities of political parties, elections, civil society organizations, and the press that inhibits public participation at the political level.

Furthermore, this legislative framework does not allow public participation in governmental policies and initiatives at the social level, allowing for greater corruption, increase of the scope of arbitrary central government decisions, decrease of bureaucratic performance, and a high level of uncertainty. Therefore, the public in Egypt distrusts the process and the outcome of the decision-making process, which, in turn, contributes to the diminishing public desire to participate in the process altogether.

National programs and policies must therefore be the outcome of a more comprehensive consultative process between the government and the public. In this respect, plans to liberalize the sociopolitical institutions of the country are needed to promote a participatory approach. Certainly, the liberalization of the political environment in Egypt will encourage civic participation and produce engaged citizenry by allowing the public to express their demands and orientations through a legitimate and clearly identified medium.

Poverty and illiteracy can be seen as a set of interrelated conditions that hinder the capacity of citizens to engage in the decision-making process in a sustainable and effective manner. However, with the economic growth that Egypt is currently experiencing, these two variables should be lessened, increasing the citizenry’s desire to engage in public affairs and control their political environment. Therefore, it is important to note that the greatest obstacles that hinder greater civic engagement in Egypt are in the military-inspired sociopolitical institutions and the repressive behavior of the state.

Public participation in Egypt is limited due to systemic, government-sponsored crackdowns on civic engagement, discussed in part two of this paper. The lack of interaction between the community as a whole and the state has contributed to the deterioration of many public services in Egypt. There are no legitimate channels that allow the public to express its concerns and demands at the national level or local level. The failure of the public education system in Egypt is a case in point.

The Egyptian public education system is currently producing a high number of dropouts and graduating low-achieving students. It is failing to produce the required human capital that is needed to spur and sustain economic growth. This failure is hindering the overall development of the country (EL Mattrawy, 2006).

The problem of the public education system in Egypt is institutional in nature. Public education, similar to other public services’ structures, suffers from the same ailments as the rigid, inflated, centralized and inefficient state-bureaucratic apparatus (Hussine, 2008). The education structure gives absolute discretion to governmental agencies and institutions in determining all financial or managerial decisions without any consultation and involvement of the community, or intended beneficiaries (Hussine, 2008).

Meanwhile, the lack of sufficient resources has impeded the government’s ability to provide the communities with adequate educational delivery, fully equipped school buildings, teachers, and instructional materials. As a result, public education has systematically failed to address teachers, parents and students needs, and failed to respond to local communities’ demands for development (Hussine, 2008).

Various experiences in similar countries have indicated that community participation and the management of educational projects and activities have helped in addressing the barriers that impede the process of achieving high-quality education, even where there is poverty and undemocratic rule. Balochistan, a poor, rural, and underdeveloped province in Pakistan, for example, was able to improve the quality and access to public education in 1998 through an initiative, known as Community Support Program (CSP), which strengthened community support for the educational process. This program aimed at generating a sense of ownership in teachers and community members through establishing an ongoing dialogue on school function, process, and desired outcomes. The process focused on the interaction of teachers and community members through weekly and monthly meetings. All parents participated with government officials in selecting their local school teachers. Community members and all those affected by the educational process were free to associate with NGOs and unions to advance their concerns to the political arena. The program was able to achieve a 159% enrollment rate18 for girls within a period of eight years. An important element for the success of this program was the commitment to public participation and community involvement (Anzar, 1999).

Similarly, the Egyptian government has passed two important initiatives in the education field aiming at increasing the public involvement, as an important factor to improve the quality of education in Egypt. However, due to the authoritarian behavior of the government and the restricted legislative framework that inhibits public participation in Egypt discussed in the two previous sections, this paper is questioning the effectiveness and the validity of these two initiatives. Therefore, this section will attempt to understand the reasons and the motives behind the current government initiatives that aim at encouraging public participation in the Education field. This part will also analyze the education system and problems to illustrate how the absence of public participation in the government decision-making process has had a dire impact of public services and impairs the country’s development

This chapter will: (1) explain the history and the structure of the public education system in Egypt; (2) discuss how this structure is limiting public participation, which in turn contribute to the poor quality of education; and (3) evaluate the current government’s initiatives that aim at improving the education system in Egypt through community involvement.

The Egyptian education system and its institutional framework have changed over time reflecting different priorities in terms of quality and accessibility. Under the monarchy, which ruled Egypt for three centuries, the education system was developed to value the quality of education over its accessibility. Therefore, education was only accessible to specific groups – foreigners, members of the upper class and elites – in order to effectively allocate the scarce resources available to generate high quality educational achievements (EL Mattrawy, 2006).

The 1952 military coup d'état, which overturned the monarchy and established the Republic of Egypt, inherited an education system that was limited in its scope in term of accessibility. During the time of 1952 Revolution, nearly 75% of the population over 10 years of age was illiterate, 90% of whom were females (Metz, 1990). The new government prioritized the goal of eradicating illiteracy by expanding education opportunities to all classes. Unfortunately, the rapid expansion of access to education was accomplished at the expense of education quality (Bridsall and O’Connell, 1999).

The education reforms and policies that were undertaken during the 1952 Revolution form the foundation of the education system today in Egypt. Certainly, many of the current problems in the education system date back to the policies developed and implemented under the 1952 Revolution government, which aimed to achieve three goals: social equality, citizens’ loyalty to the new government, and national security.

For the new regime, education was seen as a sign of equality and justice that the 1952 Revolution had promised to accomplish for everyone (Sayed 2006; and Metz, 1990). To realize social equality, the new government had to expand education opportunities for all citizens by financially sponsoring pre-school to universities and higher education levels, without considering the limited resources available to the country at that time.

Furthermore, the new government used free education to expand the middle class, the main supporters of the Revolution. At the very beginning, the 1952 government faced enormous international and internal pressures that jeopardized its stability and its legitimacy. Internationally, several western countries led by the British government, which had many economic interests in Egypt at that time (specifically controlling the Suez Canal) had planned to support the monarchy and overturn the new government (Metz, 1990). However, the internal weakness of the British government at that time inhibited Britain from overthrowing the new government. Internally and soon after the Revolution, several other populist revolutions erupted and opposition groups position strengthened, particularly the rise of Muslim Brotherhood has weakened the government position (Metz, 1990), discussed in part one of this paper.

Free education was believed to be the solution for reinforcing national identity and the 1952 Revolution ideology (Sayed, 2006). By expanding educational opportunities to those groups that were denied access to it under the monarchy, the new government believed that it would command citizen loyalty to the new regime and ensure its legitimacy (Sayed, 2006).

However, this argument does not explain why the government chose to adopt a highly centralized education structure as a solution. The institutional structure of the education system can further be explained by referring to Graham Allison’s organizational behavior model. The military government of 1952 felt strong pressures to stabilize its regime. To respond to such a critical issue as an act that threatens its national security, the government of 1952 relied on its militaristic organizational capacity and standard operating procedures [SOPs] (Allison, 1999). Certainly, the state of Egypt, following the success of 1952 Revolution, has approached many social issues such as education with a military mindset to protect its reign.

The reliance of the 1952 government on its organizational capacity and SOPs was evident in the adaptation of a highly centralized and highly controlled public education structure resembling the military institution. This education structure was believed to achieve national security by limiting the ability of any group or individual aiming at changing the status quo. This founding concept explains why the education system does not give community members, parents, teachers, or students a voice to influence the education process and its outcomes.

Essentially, the institutional framework of the education system gives the Ministry of Education (MOE) a monopoly over the financial and managerial decision-making process. MOE retains key decisions on curricula development, determining national evaluation criteria, deciding budgets for educational districts, hiring and determining salaries and incentives for teachers, and training needs for teachers and administrators (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report 2004; and Law 139/1981).

Using this security frame, the government adopted militarized solutions that may not always have been appropriate for resolving social issues particularly educational problems. It has restricted the activities of unions, non-governmental organization (NGOs), and set a ban on the freedom of associations hindering the ability of the education system to evolve and to advance in accordance to the communities’ and stakeholders’ demands and needs.

In recent years, a growing frustration among the public, parents and students alike, toward the troubled state of the education system was heightened. There are two particular events that have triggered this growing desperation and dismay of parents, students, and teachers with the education system in Egypt. The first event is the death of 10-year-old two students in 2007, due to the corporal punishment techniques used in public schools (Abdoun, 2008), where a fourth grade student at Saad Othman Primary School in Alexandria died after being kicked in the stomach by his mathematics teacher for not completing his homework (Abdoun, 2008). The second child died after her mathematics teacher asked the student to stand up against the wall for not completing her homework. When the teacher asked a school worker to bring him a stick to punish the undisciplined students, the student started shaking and passed away out of fear.

The second event is related to the organized cheating on national exams, where several teachers and parents received sentences of between 3 and 15 years in prison for leaking and buying national examinations (Dhillon, Fahmy, and Salehi-Isfahani, 2008). A group of teachers and student leaked and sold in Minya City the national high school certificate exam, Egypt’s feared and reviled exam. The scandal was publicized as the group sold the examination to a large number of students and parents to make bigger profit.

These recent events expose the growing discontent with the education system and underline the deterioration of the education system as a whole. Currently, the education system in Egypt suffers from poor overall quality. Its infrastructure is deteriorating, corporal punishment is widespread, the dropout rate is increasing, and unemployment among school graduates is pervasive. These problems in the education system are all attributed to the institutional structure formed under the 1952 Revolution, which supported free education and centralized all managerial and financial decisions at the discretion of government agencies, limiting public participation in the education process. Additional factors are attributed to the current control mechanism imposed by the government to control opposition, but in turn inhibits civic engagement at all levels.

Free education is still safeguarded by the Egyptian Constitution (Article 18, 19 & 20). As ideologically virtuous as it sounds, free education is not feasible, considering the very limited resources of the country. Consequently, from 1952 to date, the public school system receives inadequate funding and trained teachers (Sayed, 2006).

More importantly, free education required a massive expansion in the government bureaucracy to support its function and its delivery. Since the 1952, education investments were not well-allocated to produce good quality education, but rather to support the expansion of its bureaucracy. As a result, public education bureaucracy expanded beyond control, while learning outcomes have been disappointing.

Currently, Egypt has one of the largest education systems in the world, consisting of 15.5 million students, 807,000 teachers, and 37,000 schools (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2008). Public schools enroll 90% of eligible students in Egypt. The education system employs the largest number of civil servants in Egypt. According to the Egypt Human Development Report, close to 1.5 million full and part-time teachers and administrators were employed by the Ministry of Education in 2005. Moreover, the statistics shows that 85% of the Ministry of Education's budget has been designated for salaries, leaving a very small percentage for maintaining and developing new schools and teaching material (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2005).

Demographic pressures and increasingly strained resources resulted in the physical disrepair of many primary schools, overcrowded classrooms, and poor teacher morale and motivation in the face of low salaries. According to United Nations Children’s Fund (UNCIEF) report, more than half of the 25,000 schools that were operating in the country in 2003 were considered unfit for educational activity and were a threat to the physical well-being of children and teachers.

In addition, teachers are underpaid and poorly qualified. The average teacher’s salary in 2007 is equivalent to $460 annually, less than half the country's average per-capita income of $1643 (Glain, 2003; and Goliath Business News, 2006). Consequently, the teaching profession is attracting low-caliber instructors at public schools, which in turn contributes to the poor quality of education in terms of content and skills received.

Furthermore, the relatively high average enrollment rate in primary school of 90% masks the high number of repetitions, dropouts, and non-completions, especially in the villagers and countryside (UNDP Human Development Report, 2008). The classroom shortage forces administrators to assign 100 students at a time in a single course and hold classes in two shifts (Glain, 2003). In a focus group conducted by CARE International NGO, a sixteen-year-old student describes the situation in her own words: “If I am a few minutes late to class, all I can see is a mouth moving, because seats far from the instructor are the only ones available in the crowded classroom.”

The shortage in schools and teachers, and overcrowding in the classroom has bred a system where corporal techniques have become the only source of punishment. The UNDP Egypt Human Development report of 2008 estimated that around 50% of children in Upper Egypt and 70% of children in urban areas are subjected to physical discipline in schools.

The excessive government control over all decisions related to the education process, including the control over education curricula and national examinations have produced low-achieving students. Schooling in Egypt became mainly driven by the need to score high grades in national examinations, which determine access to university enrollment. “These exams do not only engender a culture of fear and frustration, but also reinforce rote memorization and stifle critical thinking and creative expression” (Dhillon, Fahmy, and Salehi-Isfahani, 2008).

As a result, many students graduate from high schools, secondary school, and universities with skills that do not match labor market requirements. This in turns leads to growing rates of unemployment. Unemployment rates among “educated youth” in 2006 (55% for high school students, 11% among tertiary graduates, and 14% among university graduates) indicate low and negative returns to secondary and university education (Dhillon, Fahmy, and Salehi-Isfahani, 2008; EL Mattrawy, 2006)

The centralization of decision-making in the field of education does not allow community members and stakeholders to be part of or influence the education process19. School principals, school administrators, and local education authorities are all appointed to their positions. Therefore, all policies related to education are left to appointed officials and bureaucrats. Egyptian citizens are not given the right to propose a law; they cannot revoke an act by the Ministry of Education; and they cannot remove appointed officials in the government.

The Impact of the National Political and Economic Environment

At the national level, community members and other stakeholders do not have proper or legal channels to voice their concerns and demands. This is attributed to the national political and economic structure that inhibits public participation, discussed in part 2 of this paper.

The political framework at the national level is one of the major impediments to public participation in the education field. It restricts citizens’ freedom of assembly, information, and association.

Under the Emergency Law implemented nationally, parents and community members cannot hold a public meeting without the approval of local authority. The authority has the absolute discretion under the law to deny their request without explanation or under the basis of protecting national security. There were no cases in which the Emergency Law was involved in the education field, because many parents, especially those from modest backgrounds, do not try to challenge the government, out of fear they will be imprisoned or ridiculed by it20.

The government control over unions’ activities is another major barrier for public participation, especially for teachers. Teachers in Egypt are underpaid. As mentioned above, the average teacher’s salary in 2007 is equivalent to $460 annually, less than half the country's average per-capita income of $1643 (Glain, 2003; and Goliath Business News, 2006). This very low salary may encourage teachers to call for change of compensation scale. However, there is only one Teachers’ Union, which is government dominated and does not provide the required space for negotiation with government. The inability for teachers to negotiate their salaries and their incentives with the government has had a dire impact on the education system.

Thus, the education system is constantly suffering from a teacher shortage in public schools. Most other teachers resort to private tutoring as a vital source of income. Many teachers, particularly those working in public schools, intentionally withhold information from students inside the classroom to force them to resort to private tuition after class. Private tutoring may cost anywhere between $5 to $30 per hour depending on the teacher’s abilities and reputation. Many low-income families have been forced to take their children out of school because they do not have the means to pay for these private tutoring, and the teachers at the school do not give them the proper information that will allow them to advance to the next grade (Glain, 2003; and Hartmann, 2008). A public schoolteacher, Soueif, further explains "if teachers don't give private lessons, they can't live, and if students don't take them they won't learn. The whole families go hungry just to afford them" (Glain, 2003).

The ban over the freedom of association, which forbids teachers, parents and other community members from cooperating with the media, NGOs, political parties, and unions, is another major barrier to public participation in the education field. This ban limits the political and legal channels, where the public at large can express their concerns and move their demands to the political agenda.

Furthermore, there is very limited disclosure of information by the government regarding education policies, practices, and budgets. The absence of a provision that permits community members and other organizations to access government information hinders their ability to check education policies and outcomes. NGOs working in the field of education usually depend on anecdotes from the community to develop and plan their activities because they have difficult time accessing official information about government education policies. More importantly, official records of educational achievement, such as enrollment and access rates, are usually exaggerated by the government.

Government control of the national newspapers, national television, and radio is another obstacle for public participation in the education field. Even though some room is available for free expression in opposition papers, journalists opposed to the government may be subjected to harassment and even prosecution under the Emergency Laws. In addition, not all groups have equal access to the media, especially national T.V. and national newspapers. On a local level, there are few effective newspapers covering local and community news and interests (UNDP Egypt Human Development Report, 2008).

Moreover, the high rate of illiteracy and widespread poverty limits the opportunity for many parents and other members of the community to actively participate in the decision-making process and the outcomes of the education system. Because of low standard of living, communities – especially in poor rural areas – often allocate very little resources to the education process. Many parents are busy making ends meet, deterring their activism and participation in school governance. There are also many parents that are uneducated, which hinders their ability to participate in the school actively. Some poor, uneducated parents feel inferior and embarrassed approaching well-educated teachers (Coster, 2005).

Despite the growing desperation and dismay of parents, students, and teachers with the education system in Egypt, there are no signs of resistance or organized movements that aim at influencing the education process. This does not mean that the community is apathetic toward their children’s future. However, the highly controlled sociopolitical environment imposed by the current regime is in habiting civic engagement. Community members and parents do not want to confront the government21. Moreover, the current education structure does not give any assurance that the public opinion would be reflected in the decision-making process. Therefore, the community has resorted to alternative methods and practices such as private tutoring and private schooling to satisfy their needs and concerns. Sadly, these alternative methods and practices, particularly private tutoring, have a very negative impact on the country’s overall development, as it widens the inequality gap and restrains household income.