Chapter 1: Introduction

Project context

Participatory research

Report organization

Chapter 2: Bram’s Addition and Burr Oaks Neighborhoods: Positive Attributes and

Challenges

What are good and livable communities?

Neighbors’ viewpoints

Revitalization and its possible consequences

Suggestions for the neighborhoods

Chapter 3: Homeowners

Background on homeowners

Home buying process

Home improvements

Advantages and disadvantages of homeownership

Suggestions to improve the housing situation for

present and future homeowners

Chapter 4: Tenants

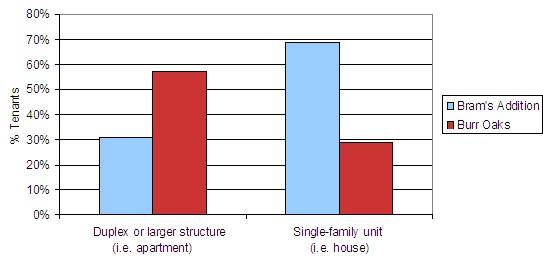

Background on tenants

Maintenance schedules and repairs

Tenant and landlord relations

Advantages and disadvantages of renting

Tenants’ perceptions and experiences with home buying

Suggestions to improve the housing situation for

present and future tenants

Conclusions

Major themes

Next steps

Future research

Lessons learned

Appendices

Appendix A. Map of Study Area: Burr Oaks and Bram’s

Addition Neighborhoods

Appendix B. South Madison Demographic Map

Appendix C. Project Announcement for Recruitment of

Research Team Members

Appendix D: Homeowner Questionnaire

Appendix E: Tenant Questionnaire

Appendix F: Consent Form for Interviews

Appendix G: Preliminary Findings, Ideas for Future

Research, and Interview Guide

Notes

About the Authors

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1: Introduction

This report is based on a participatory research project conducted in the Bram’s Addition and Burr Oaks neighborhoods, which are located in the Southside of Madison, Wisconsin. The research team was mainly comprised of individuals with connections to South Madison with a few additional members from the University of Wisconsin (UW). Together they determined objectives, developed questionnaires for homeowners and tenants, constructed a user-friendly consent form, and interviewed residents.

The main goal of the research was to achieve an understanding of the housing situation and the neighborhoods from multiple perspectives and to develop suggestions to improve the neighborhood and housing situation that reflect the concerns of the community. To capture a diversity of viewpoints, the research team interviewed homeowners and tenants from both neighborhoods.1 This is a three phase project: the first phase was training and research; the second phase included data analysis, report writing, and dissemination of findings; and in the third phase, the research team will work to implement recommendations and action plans to improve the neighborhoods and the housing situation for residents.2

The research team hopes that by sharing this information other community members, organizations, and local governmental officials and staff will become their partners in learning, discussing, and working to make the necessary changes that will improve the housing situation for homeowners, tenants, and landlords and address existing issues affecting the neighborhoods.

Here we share some local history and demographic and physical characteristics of the South Madison area, explains the housing issue, and discusses participatory research. South Madison for the purpose of this study is the Southside neighborhoods that are adjacent to Park Street between Wingra Creek on the north and the Beltline Highway on the south.

I. Project context

A. South Madison

Park Street, which is considered the “Main Street” of the Southside, intersects other arterial streets and the Beltline Highway to connect commuters with destinations throughout Madison and the outlying communities (see Map of Study Area: Burr Oaks and Bram’s Addition neighborhoods, Appendix A). On the one hand, living along the corridor is an excellent location because of its close proximity to major destinations and ease of transit. In addition, the Park Street corridor is as an international street with restaurants and local shops reflecting the diverse community that thrives in the surrounding neighborhoods. On the other hand, Park Street is a six lane3 state highway that has traffic volumes ranging from 20,000 to 48,000 cars per day depending on the location.4 This corridor presently caters to vehicular transportation and has minimal pedestrian and bicyclist amenities and connections to neighborhood streets. Due to these conditions, this corridor has become a barrier between the west and east portions of South Madison. This heavy traffic and man-made barrier, which are constantly cited as concerns in the community, have led to partnerships where local stakeholders are working to transform Park Street into a multi-modal corridor with places and opportunities for people to gather and connect. A coffee shop has opened with sidewalk seating and farmers from the South Madison Farmers’ Market sell their produce along the corridor. The future is bright and the energy to revitalize the area is strong.

The vibrancy that is the future of Park Street is already seen in the surrounding South Madison neighborhoods where there is an energy radiating from the community, people, and greenery. There are mature trees growing tall, green lawns, community gardens, sprouting flowers, kids playing and riding bicycles, residents in their yards or walking on the sidewalks, and people chatting with each other. Take a walk down the streets and residents say hello. These are the neighborhoods of Bram’s Addition and Burr Oaks.

These neighborhoods have a rich history that began in the late 1800s. “While the settlement of South Madison began late in the 19th century, it was hastened by the destruction of the Greenbush neighborhood, (‘the Bush’), bulldozed in the late 1950’s as Urban Renewal came to Madison.”5 The Bush (located just north of South Madison) was “an ethnic enclave where immigrants black, white, and Jewish from Eastern and Western Europe settled, in part because they were not welcome in other parts of Madison.”6 Longtime community activist Richard Harris, Ph.D., “remembers the 1930’s and 1940’s when parts of South Madison were still a swamp.” Ben Parks, who came to Madison in 1953, recalls the “outhouses in the neighborhood because people did not yet have indoor plumbing. Melva McShan remembers neighbors raising chickens and pigs in South Madison back when Bram’s Addition was an outlying area commonly known as ‘Hell’s Half-acre.’”7

As displaced Bush residents moved south, this increase in population resulted in the redevelopment of land into a variety of uses; paving of streets; installation of curbs, gutters, and sidewalks; building of storm and sanitary sewers; and planting of trees. In 1966, John Nolen Drive, a causeway that runs along side South Madison, was built and linked South Madison to downtown. This new road further contributed to an increase in population and development.8

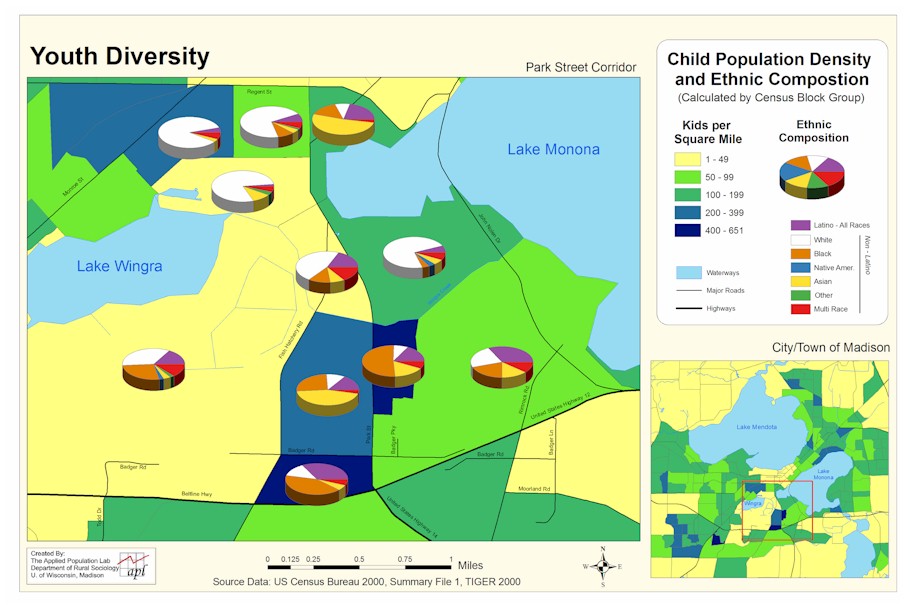

To this day, South Madison has a diverse ethnic population. South Madison has the most diverse census tract in all of the City of Madison with the breakdown as follows: 31.5% are White, 31.2% are Black, 21.1% are Asian or Pacific Islander, 20.7% are of Hispanic Origin (any race), 4.5% are two or more races, 0.5% are Native American, and 11.1% are classified as Other.9 From 1990 to 2000, these neighborhoods experienced a 503.8% increase of persons of Hispanic origin compared to 119.6% for City of Madison (Table 1.1). For more information regarding comparisons between Bram’s Addition, Burr Oaks, Town of Madison, and City of Madison, see Table 1.4.

In addition, this area is economically disadvantaged. In 1999, families living in poverty were four times higher in the project census area (26.9%) than the City of Madison (5.8%), and the median household income of $26,296 was less than the Citywide median of $41,941.10 There are 3,829 residents in the census area with a larger concentration of young people than the City of Madison as whole11 (see South Madison Demographic Map, Appendix B).

|

Table 1.1 Comparison

of economic and housing indicators between

South Madison and City of Madison12 |

||

|

Economic

and housing indicators |

South Madison |

City of Madison |

|

Change in Hispanic population from 1990-2000 |

503.8% |

119.6% |

|

Families in poverty |

26.9% |

5.8% |

|

Household median income |

$26,296 |

$41,941 |

|

Owner-occupied homes |

21.8% |

47.7% |

|

Renter-occupied homes |

78.2% |

52.3% |

As compared to the rest of Madison, South Madison is less expensive and has different mixes of housing types and ownership arrangements. In 2000, 21.8% were owner-occupied and 78.2% were renter-occupied, as compared to 47.7% owner-occupied and 52.3% renter-occupied for the City of Madison.13 As in other parts of the country, Madison housing prices have increased significantly in the past decade with the price of the average valued home increasing 104% from $109,686 in 1994 to $223,800 in 200514 (Box 1.1). In 2000, Bram’s Addition had a median value of $91,200 for an owner-occupied home, while Burr Oaks had a median value of $78,200 for the area south of West Badger and $93,900 for the area north of West Badger. This is compared to a median value for an owner-occupied home of $139,300 for the City of Madison. For rental properties in 2000, Bram’s Addition had a median gross monthly rent of $558 for the study area, while Burr Oaks had a median gross monthly rent of $577 for the area south of West Badger and $584 for the area north of West Badger. This is compared to a median gross monthly rent of $644 for the City of Madison15 (Table 1.4).

|

Box 1.1 Putting

housing prices in perspective

|

|

To put

the housing prices in perspective with wages earned, a household

would have to earn $43,867 gross per year to pay the necessary

monthly $1096.68 (mortgage/real estate taxes/insurance) that

would allow them to purchase a $157,000 house at 6.450% interest

and amortized for 30 years.16

If the household is interested in renting an apartment for

$647, “in order to afford this level of rent and utilities,

without paying more than 30% of income on housing, a household

must earn $2,157 monthly or $25,887 gross annually.17

Assuming a 40-hour work week, 52 weeks per year, a person would

have to earn $12.45/hour to afford this housing and not pay more

than 30% of their income.”18 |

B. The housing issue

South Madison residents’ concerns about the status of the housing stock and affordability surfaced when the South Metropolitan Planning Council (SMPC)19 worked with community residents and other stakeholders between 2000 and 2001 to develop a vision for South Park Street.20 South Madison residents expressed concerns such as revitalization will drive up rents, taxes may increase, and people will never be able to afford the purchase of housing in South Madison. These concerns are also shared by experts in the housing field, as expressed by Paul Jasenski, who has 20 years experience as the Housing Development Manager for Common Wealth Development.21 According to Jasenski, “Even ten years ago, I never thought housing prices would get so high in the Willy [Williamson] Street neighborhood, and I predict in the future we are going to be seeing the same thing happen in South Madison.”22

South Madison residents who participated in the Park Street visioning process also expressed concerns regarding past revitalization efforts in Madison because they believed that community members had little voice or influence in the planning. This top-down planning “contributed to tensions in the area because they were imposed on community members rather than cooperatively planned.”23

In order to address community concerns and increase involvement of local residents in the revitalization efforts, SMPC collaborated with University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-Madison) to develop community teams. Community teams are comprised of volunteer residents who work to gather information on a topic of interest to the community; exchange this information and acquire feedback from the larger South Madison community; and collaborate with their neighbors, businesses, and government to implement physical and policy improvements.

The first community team to be developed focused on housing due to residents’ concerns that a consequence of the revitalization would be a loss of affordable housing. The South Madison Housing Community Team’s goals are to 1) ensure quality and affordable housing, 2) rehabilitate existing housing stock, and 3) build community. They realized to gain a full understanding of the housing issue it was necessary to gather information in a systematic manner and involve underrepresented groups in the process. Thus, they obtained funding to embark on an innovative participatory research project called South Madison Housing Stories and Experiences. The goals for this project were to be inclusive of residents in the research process and to thoroughly and systematically collect information about housing from a variety of perspectives (homeowners, tenants, and landlords). The purpose of collecting this information was to develop a workable action plan for housing stock and policies that reflect the concerns and interests of the South Madison community.

The study area for South Madison Housing Stories and Experiences project is the Bram’s Addition and Burr Oaks neighborhoods. These neighborhoods were chosen because they are located adjacent to Park Street and will be affected by the revitalization plans and are comprised of significant numbers of residents who were economically disadvantaged and underrepresented. In addition, local residents expressed concern about maintaining affordable, quality housing and not displacing current residents.

II. Participatory research

A unique aspect of South Madison Housing and Experiences is that it focuses on engaging local voices in two ways: 1) residents are engaged in all aspects of the research process including the study design and interviewing community members and 2) residents’ opinions and experiences are collected. This type of research process, called participatory research, is a valuable method for building the skills of local residents, gathering reliable and useful information, strengthening collaborations, and increasing participants’ ownership of the project as a whole. Building collaborations and increasing ownership during the research process builds a strong foundation for varied stakeholders working together to initiate action that can influence community changes and policy.

Participatory research taps into local knowledge and gives voice to individuals whose ideas and concerns are critical for a full understanding of an issue. This differs from a traditional research model that has outside researchers, usually from a university, seek information pertaining to their interests and community members answer questions from which they rarely see outcomes. Furthermore, in community planning, there can be a tendency towards relying on existing demographic information and public forums, which many times draw the same players, without more systematic inclusion of all the possible resident opinions and experiences. Considering that residents are the stakeholders who will directly experience the positive and negative effects of community changes, their involvement for identifying issues and implementing changes is critical.

In participatory research, community members are active in the entire research process that includes setting objectives, designing questions, and gathering information.24 Thus, the research focus and outcomes reflect resident needs, interests, and circumstances. Resident involvement during the research stage can also increase the likelihood of their engagement in working towards change in the community. This study demonstrates that there are a significant number of residents in South Madison that value the area, have long-term hopes and visions for their neighborhood, and can be a base for building a stronger community. The following is a description of the participatory research process that was used in this study.

Recruitment. In fall 2004, the project coordinators25 publicized this project (see Project Announcement, Appendix C) and brought together local residents to form a research team that represented a broad range of backgrounds (e.g. economic, homeowner/tenant, race/ethnicity, age). The research team was primarily comprised of individuals with connections to South Madison. Their connections to South Madison included currently residing or having lived in the study area and/or working on issues associated with South Madison.

Training. When recruited to work on a participatory research project, community members come with their own expertise that they have gained from their life experiences. They have an extensive knowledge of their community, but may lack the research skills and an understanding of how to develop a research project. Thus, in participatory research, the training is an essential component in order to expose community members to the concepts of research, learn skills and techniques, and develop a well-designed project.

During weekly training meetings, a facilitator, who is also a local resident,26 introduced the research team to the general concepts of research (e.g. triangulation, bias, confidentiality, recording information) and incorporated exercises on objective setting, team building, and presenting. In order to gain experience, research team members learned a technique, such as interviewing, and then practiced it on each other and their family and friends.

Research Design.

During the training period (September 2004 to May 2005), the

research team developed a research design that included 1) how

information would be gathered (i.e. the methods), 2) who would be

interviewed (i.e. sample), and 3) how residents would be approached

and their participation obtained (i.e. obtaining consent). Though

the original intent of South Madison Housing Stories and

Experiences was to study housing, the specific objectives (Box

1.2) and research design were a product of the research team’s

active involvement.

|

Box 1.2 Project objectives |

|

The

research team wanted to learn from their neighbors: 1) qualities that make a good housing situation and desirable neighborhood for homeowners and tenants, 2) main issues regarding housing for homeowners and tenants, and

3) needs to be addressed in terms of housing and

neighborhoods. |

a) Research Methods. In order to learn more about their project objectives, the research team decided to develop questionnaires (see Homeowner and Tenant Questionnaires, Appendices D and E) and interview residents individually rather than collectively (e.g. focus groups). In South Madison, there have been other opportunities for obtaining collective discussion such as during planning meetings and other forums.27 The research team believed that it was important for this project to complement existing information by obtaining individual data on each resident and for each respondent to have privacy in answering questions without others present.

Two questionnaires were constructed: one for tenants, and another for homeowners that included both open-ended and closed-ended questions.28 The research team decided they would conduct door-to-door interviewing in order to talk to residents individually.

b) Sample. After the research team decided to conduct door-to-door interviews, they needed to decide on a systematic method to choose residents for interviews. The research team wanted a systematic method for selecting residents in order to ensure that their findings reflected the experiences and opinions of all the residents and not, for example, only particular individuals they knew. The research team decided to use a sampling technique called “cluster sampling.” In this approach, they assigned numbers to each block in the Bram’s Addition and Burr Oaks neighborhoods and then randomly selected 10 blocks from each of the neighborhoods. Thus, each block had the same likelihood of being selected. The research team members then interviewed a resident over the age of 18 from each household on the blocks selected.29 The research team decided to use cluster sampling rather than other techniques30 for selecting residents because they wanted a random sample with a modest budget and time frame. Cluster sampling is ideal for these purposes since research team members interview on designated blocks and could visit one resident after another without having to spend time looking for separate houses throughout the neighborhoods. Due to accessibility issues, buildings with more than four units were left out of the sample. Thus, the sample and, therefore, the study do not include residents who live in large apartment buildings.

Comparing the project’s sample to the neighborhoods’ populations (Table 1.3), the major difference between them is in ownership status. Due to the decision to exclude any building structures with more than 4 units (see section, Future research), the research team interviewed many more homeowners and many less tenants than is reported in the 2000 Census information for the two neighborhoods. This means that the large apartment complexes where many tenants in both Bram’s Addition and Burr Oaks reside were not part of our sample. This decision may explain other observed differences between the sample and the actual population of both neighborhoods. For example, the research team interviewed more residents ages 40 to 59 and more residents with a Bachelor’s or Post College education than is observed in the actual population of both neighborhoods. This may mean that younger people and those with less education are more likely to be tenants living in the larger complexes. Due to the decision to exclude larger structures, the sample is representative of those living in building structures of 4 units or fewer and not representative of those living in larger structures.

c) Obtaining Consent. Because the project was associated with UW and the research team wanted to make sure that they abided by the standards of ethical research, they collaborated with a faculty member at the UW-Madison and acquired permission to conduct the research from the UW’s Human Subjects Committee of the Institutional Review Board. Since the information collected would be anonymous (i.e. names would not be collected and the information could not be tracked back to any particular resident), it was not obligatory for the research team to obtain signed consent forms. However, the research team wanted the residents to be able to understand the project goals, objectives, and the way the information would be used, so they constructed a user-friendly consent form. The research team members reviewed this form at the beginning of each interview and left one with each resident for future reference (see Consent Form for Interviews, Appendix F).

Data Collection. With practice under their belts and housing on their minds, research team members knocked on doors in Bram’s Addition and Burr Oaks neighborhoods in the summer of 2005 (Table 1.2). The research team worked in pairs to facilitate recording and cross-checking of information.31 Each pair worked in designated blocks and they decided who would be the interviewer and who would be the recorder. The residents interviewed were very friendly and generous with their time and invited research team members to sit on their stoop or lawn chairs, while patiently answering questions from twenty minutes to sometimes over an hour. The research team first worked on interviewing residents from one neighborhood. Due to the generosity of respondents’ time and interest in answering questions, the interviews took longer than expected in the first neighborhood so additional research team members were recruited to assist in the second neighborhood.

Analysis. After the research team collected the data, both quantitative and qualitative information was entered into a database and analyzed. Two questionnaires generated an enormous amount of data and allowed for rich analysis. However, the analysis was more labor intensive and time consuming than expected and required certain technical skills that had not been originally anticipated. Due to the work involved, only a few research team members (facilitator, project coordinators, and one community member) participated in the analysis and interpretation of the initial findings rather than the whole research team (see Conclusions--Lessons learned).

The qualitative information obtained through the open-ended questions was examined for similarities and differences and then coded. In some cases, in order to assess the relationship between different groups, statistical analysis was conducted. Using statistical tests and checking for whether there is statistical significance between groups can show whether the observed differences between the groups being compared are a product of chance alone or evidence of a real relationship. The analysis that was conducted on the data is shown in tables throughout the report. The differences that are statistically significant are indicated by asterisks: two asterisks indicate stronger evidence of a relationship than one asterisk.

Feedback and Action. After a summer of speaking with South Madison residents, the research team learned a great deal about their neighbors, housing situations, and community. These findings are explained in this report and are being shared at community meetings and other venues. The findings will also be presented in other written material such as fact sheets, newsletters, and websites. This dissemination of information allows research team members to present their findings, request feedback, and invite collaboration. This dissemination of information will assist in the building of a collaborative partnership between community members and other stakeholders so they can work together to improve housing policies and stock; better the situation for homeowners, tenants, and landlords; and address any existing issues affecting the neighborhoods.

The development of action plans and the target recommendations implemented will depend on the interests of the collaborating partners, feedback from the findings, and available support.

III. Report organization

The

remainder of the report explains the research findings. Next, we discuss the neighborhoods’ positive attributes and areas for

improvement. Then we focus on homeowners’ perspectives on

the housing situation, followed by a discussion of tenants’

perspectives. Each section includes suggestions that arose

from speaking to residents and from the research team’s

findings. The Conclusion provides next steps and

future research, and lessons learned from this project. This report,

as well as all appendices, can be accessed through web links.32

|

Table 1.2 Demographic

characteristics of individuals interviewed |

|||

|

Demographic characteristics |

Homeowners |

Tenants |

All residents interviewed |

|

Neighborhood33 |

|

|

|

|

Bram’s Addition (n=5934) |

57% |

49% |

54% |

|

Burr Oaks (n=50) |

43% |

51% |

46% |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

Female (n=62) |

51% |

70% |

58% |

|

Male (n=45) |

49% |

30% |

42% |

|

Race and/or ethnicity35 |

|

|

|

|

White (n=46) |

49% |

38% |

45% |

|

Black or African American (n=33) |

29% |

38% |

32% |

|

Latino or Hispanic (n=8) |

7% |

9% |

8% |

|

Asian (n=12) |

13% |

9% |

12% |

|

Other: Bi-racial/Bi-cultural, etc. (n=3) |

1% |

6% |

3% |

|

Education |

|

|

|

|

Less than High School or some High School (n=19) |

21% |

14% |

18% |

|

GED or High School Diploma (n=21) |

13% |

32% |

20% |

|

Some college or Associate’s Degree (n=30) |

25% |

35% |

29% |

|

Bachelor’s Degree or Post College (n=34) |

40% |

19% |

33% |

|

Stress36 |

|

|

|

|

About 30% or less (n=41) |

40% |

44% |

41% |

|

31% to 50% (n=27) |

30% |

22% |

27% |

|

More than 50% (n=31) |

30% |

33% |

31% |

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

18 to 29 (n=23) |

10% |

43% |

22% |

|

30 to 39 (n=20) |

21% |

16% |

19% |

|

40 to 49 (n=26) |

32% |

11% |

25% |

|

50 to 59 (n=24) |

24% |

22% |

23% |

|

60 to 69 (n=8) |

9% |

5% |

9% |

|

70 or more (n=4) |

4% |

3% |

4% |

|

Length of time in South Madison |

|

|

|

|

Less than a year (n=13) |

10% |

16% |

12% |

|

1 to 4 years (n=28) |

19% |

41% |

26% |

|

5 to 10 years (n=19) |

16% |

22% |

18% |

|

11 to 20 years (n=26) |

30% |

14% |

24% |

|

More than 20 years (n=21) |

26% |

8% |

20% |

Total number of residents |

72 |

37 |

109 |

|

Table 1.3 Demographic characteristics of residents 18 years or older of Bram’s Addition (BA) and Burr Oaks (BO)* compared to residents interviewed (sample)

|

||||||

|

Demographic characteristics |

BA (n=654) |

BA sample (n=59) |

BO (n=2,089) |

BO sample (n=50) |

BA & BO (n=2,743) |

BA & BO sample (n=109) |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Female |

349 (53%) |

32 (55%) |

1016 (49%) |

30 (61%) |

1365 (50%) |

62 (58%) |

|

Male |

305 (47%) |

26 (45%) |

1073 (51%) |

19 (39%) |

1378 (50%) |

45 (42%) |

|

Race and/or ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

White |

186 (28%) |

24 (45%) |

799 (38%) |

22 (45%) |

985 (36%) |

46 (45%) |

|

Black or African American |

283 (43%) |

18 (34%) |

425 (20%) |

15 (31%) |

708 (26%) |

33 (32%) |

|

Latino or Hispanic |

80 (12%) |

6 (11%) |

498 (24%) |

2 (4%) |

578 (21%) |

8 (8%) |

|

Asian |

79 (12%) |

3 (6%) |

329 (16%) |

9 (18%) |

408 (15%) |

12 (12%) |

|

Other: American Indian, Bi-racial etc. |

26 (4%) |

2 (4%) |

38 (2%) |

1 (2%) |

64 (2%) |

3 (3%) |

|

Education* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Less than High School or some High School |

203 (37%) |

9 (16%) |

490 (31%) |

10 (21%) |

693 (32%) |

19 (18%) |

|

GED or High School Diploma |

134 (25%) |

9 (16%) |

367 (23%) |

12 (26%) |

501 (23%) |

21 (20%) |

|

Some college or Associate’s Degree |

164 (30%) |

16 (28%) |

531 (33%) |

14 (30%) |

695 (32%) |

30 (29%) |

|

Bachelor’s Degree or Post College |

44 (8%) |

23 (40%) |

213 (13%) |

11 (23%) |

257 (12%) |

34 (33%) |

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18 to 29 |

190 (29%) |

11 (19%) |

791 (38%) |

12 (25%) |

981 (36%) |

23 (22%) |

|

30 to 39 |

152 (23%) |

11 (19%) |

547 (26%) |

9 (19%) |

699 (25%) |

20 (19%) |

|

40 to 49 |

138 (21%) |

15 (26%) |

357 (17%) |

11 (23%) |

495 (18%) |

26 (25%) |

|

50 to 59 |

63 (10%) |

15 (26%) |

180 (9%) |

9 (19%) |

243 (9%) |

24 (23%) |

|

60 to 69 |

51 (8%) |

5 (9%) |

97 (6%) |

3 (6%) |

148 (5%) |

8 (8%) |

|

70 or more |

60 (9%) |

0 (0%) |

117 (6%) |

4 (8%) |

177 (7%) |

4 (4%) |

|

Ownership status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Owner-occupied units |

100 (28%) |

41 (69%) |

258 (24%) |

31 (62%) |

358 (25%) |

72 (66%) |

|

Renter-occupied units |

256 (72%) |

18 (31%) |

823 (76%) |

19 (38%) |

679 (75%) |

39 (34%) |

* Information is from the 2000 census. For BA and BO, 2000 census information counts education for those 25 and older; for research sample, education is counted for all residents interviewed (18 years or over).

|

Table 1.4 Comparison of economic and housing indicators between Bram’s Addition, Burr Oaks, Town of Madison, and City of Madison*

|

||||

|

Economic and housing indicators

|

Bram’s Addition |

Burr Oaks |

Town of Madison |

City of Madison |

|

Change

in Hispanic population from 1990-2000 |

241% |

562% |

524% |

119.6% |

|

Persons

with income below poverty |

31% |

32% |

24% |

15% |

|

Household median income |

$30,625 |

$22,540 (south of W. Badger)

$28,571 (north of W. Badger)

|

$29,766 |

$41,941 |

|

Owner-occupied homes |

28% |

24% |

24% |

48% |

|

Renter-occupied homes |

71% |

76% |

76% |

52% |

|

Median value of owner- occupied homes |

$91,200 |

$78,200 (south of W. Badger)

$93,900 (north of W. Badger)

|

$97,200 |

$139,300 |

|

Median gross monthly rent |

$558 |

$577 (south of W. Badger )

$584 (north of W. Badger)

|

$584 |

$644 |

*Information from 2000 census.

Chapter 2: Bram’s Addition and Burr Oaks Neighborhoods: Positive Attributes and Challenges

Communities, urban planners, and developers have discussed and debated for years the attributes that result in a good and livable neighborhood. For South Madison Housing Stories and Experiences, the research team asked the Bram’s Addition and Burr Oaks residents to share their thoughts on this issue. The qualities of the neighborhood affect how residents’ perceive their overall housing situation; therefore, the research team thought it was important to include questions on the neighborhood in this project. Here we present residents’ perceptions of their neighborhoods’ positive attributes and challenges, while also offering suggestions for improvement.

I. What are good and livable communities?37

Currently, communities, urban planners, and developers are focusing attention on identifying the characteristics of good and livable communities and how they are created. In the period after World War II, the subsidizing of highway development, home buying loans that favored single-family homes instead of multi-unit dwellings, development of strip malls, increasing reliance on automobiles, and a variety of other factors, spread cities outward and produced urban sprawl. This development resulted in an increase of automobile usage and need for parking lots, highways, and streets that was detrimental to pedestrians and not conducive to bicycles. However, in the last few decades there have been movements, such as New Urbanism, that seek to once again develop community among neighbors by decreasing traffic, eliminating sprawl, and developing livable and walkable communities.

One urban writer and community activist, Jane Jacobs, observed the positive attributes of neighborhoods in urban settings. In her influential book that has become a classic, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), Jacobs highlighted that economic, architectural, and human diversity was critical for vibrant cities and argued that mixed-use planning, meaning dwellings with retail and short walkable blocks, was essential for communities to thrive; not orderly development plans that replaced whole neighborhoods.

Such discussions regarding the principles of design are important for existing neighborhoods as well as for new developments. A recent local effort to engage in these discussions, Great Neighborhoods: How to Bring Them Home,38 defines the characteristics of great neighborhoods and gives examples of local communities that include these qualities or housing developments trying to incorporate them. The definition in the Great Neighborhoods report reflects Jane Jacob’s theory of walkable and livable cities.

“Great neighborhoods bind homes together with active and pedestrian-friendly streets, high-quality civic open spaces, local and distinctive shopping opportunities, flexible and appealing employment locations, accessible and neighborhood-scaled schools, preserved wild spaces, and more.”39

The Bram’s Addition and Burr Oaks neighborhoods have many of the positive attributes defined in Great Neighborhoods and include different types of housing (price, size, layout, ownership), a mixed-use area (residential as well as retail), human scaled streets (short blocks in the neighborhood with sidewalks), and nearby amenities and public spaces (stores, restaurants, social services, and parks).

The research team was interested in understanding what residents’ believed are the positive qualities that make Bram’s Addition and Burr Oaks good and livable communities, as well as the problems that need to be addressed. The remainder of Chapter 2 presents community members’ perspectives on their neighborhoods’ positive qualities, difficulties, as well as suggestions for improvement.

II. Neighbors’ Viewpoints

A. Social aspects

1. Sense of community and good neighbors

Proponents for good and livable communities strive to cultivate a “sense of community,”40 which means that residents have good feelings towards their community in terms of the general atmosphere and the people. A sense of community is the most common reason homeowners (53%) and tenants (54%) in Bram’s Addition and Burr Oaks stated for liking their neighborhood (Table 2.2, page 21).

A sense of community was also a reason residents were drawn to these neighborhoods and continue to live here (Table 2.3). Whereas only 14% of homeowners and 19% of tenants mentioned having moved here because of a sense of community, 32% of homeowners and 54% of tenants commented that it was a major reason why they continued living here. This strong sentiment did not vary by race and ethnicity.

The positive interactions residents had with their neighbors were an important component in their upbeat perceptions towards their community. The neighborhood offers opportunities (e.g. public spaces, layout of streets) for residents to get to know one another, watch out for each other, and respect one another. Some comments made by residents are the following:

“people help each other and talk to you”;

“there is good communication with the neighbors”;

“there are good people who live here, they watch out for each other”;

“kids give back by helping the neighbors”; and

“kids can play outside with kids of all ages.”

Yet, some residents felt that there was a need to improve relations both among community members and between outsiders (i.e. strangers, visitors) and local residents (Tables 2.4 and 2.5). Within the neighborhood, poor relationships among community members seemed to focus on a lack of respect for other residents such as being noisy, or strangers hanging out and being disrespectful or loud. As one resident said, “it’s a few neighbors and their visitors are noisy.” Residents in Bram’s Addition mentioned a need to improve community relations more than Burr Oaks.

Furthermore, residents believed that the greater Madison community has a negative perception of South Madison and thinks of the area as an undesirable place to live. They believe that their neighborhoods receive bad press from the media and they would like there to be “more understanding of [South Madison] as a nice place.” (For more information, see Safety and neighborhood disturbances, page 16.)

2. Shared personal and cultural background and diversity

One of the major reasons homeowners and tenants moved into the Bram’s Addition and Burr Oaks neighborhoods was that they had either personal or cultural ties with other residents. This was commonly expressed by homeowners (33%) and tenants (35%). A personal tie meant that a resident or a spouse was born and raised in the neighborhood or that someone they knew such as a friend or relative lived in the community or nearby. A cultural tie meant that residents shared identities, such as religion or race or ethnicity, with other residents. A few residents said that they liked that their neighbors resembled their cultural background, one resident said he liked that others in the neighborhood “looked like me.” One Asian resident said that he liked that there were a lot of other Asian families in the area. This category, shared personal and cultural ties, was cited fewer times as a reason that residents stayed in the neighborhoods.

There were a few differences between residents. While 39% to 59% of African Americans, Latinos, and Asians mentioned personal and cultural ties as a reason for moving into the area, it was only mentioned by 28% of Whites. Also, personal and cultural ties were mentioned frequently by residents who have lived in South Madison over 20 years. For example, 52% of residents who had lived in the area for over 20 years mentioned personal and cultural ties as a reason for moving here compared to 23% of residents who had lived in the area for less than one year.

On the other side of the coin, far fewer people mentioned that diversity, in terms of residents’ differing cultural and economic backgrounds, was a reason for moving here and continuing to live here. Residents expressed what they liked about diversity in South Madison:

One resident also shared another side of the diversity issue. She shared that she felt discriminated against in the community and that “some residents have been here longer time and are nervous about accepting new people. There is no interacting cross race or cross culture.”

Given the prevalence of economic and cultural diversity in these neighborhoods, the improvement of community relations and development of collaborations among diverse groups is an important goal. It should be noted that this study did not set out to examine issues of diversity and, therefore, sheds little light on this important topic (see Conclusion--Future research).

“different lifestyles get along”;

“[South Madison is] so diverse culturally, Asian-American families, black folks, old folks”;

“I like diversity, it enriches me”; and

”cultural diversity and economic diversity, everyone is not middle class.”

3. Safety and neighborhood disturbances

The main concern residents had about their neighborhoods was safety and neighborhood disturbances. Fifty-three percent of homeowners and 52% of tenants mentioned issues of safety and neighborhood disturbances as aspects of what they did not like about their neighborhood.

Drugs and crime were of major concern. Some residents stated that there were known drug houses in the neighborhood and they had complained to the police and the City of Madison, but the activity continued. One resident, who lived near a drug house known by neighborhood residents, shared her frustrations and concerns with research team members for over two hours. She described how cars were constantly driving up to the drug house and how several times people looking to buy drugs mistakenly knocked on her door. In addition, she mentioned that there were fights and there were times when she was fearful that the arguments would escalate into gunfights and endanger the neighborhood children. She knew the landlord was aware of the problems and that neighbors had called the police, but she had yet to see any changes.

Another homeowner who was frustrated about the drug dealing that goes on near her home and was concerned about the safety of her children stated, “drugs and dealing is the number one concern – [it happens] in our alley and there is a crack house nearby, there is lots of traffic [due to drug dealing]. We called the cops [about the drugs] but there is racial profiling and they are not very friendly. We don’t want our kids going up there [the alley] because of the problems. In the afternoon, there is lots of action; people are hanging out.”

In addition, residents believe that people drive their cars too fast down neighborhood streets and endanger children. As one resident commented, “It is the way people drive up and down the street – they don’t pay attention to children. This is very residential and there are lots of kids.” One other complaint was noise, especially from people hanging out in cars and some community members thought this was possibly due to drug dealing.

The percentage of residents concerned about safety was roughly similar across neighborhoods (49% in Bram’s Addition and 56% in Burr Oaks). Homeowners and tenants of all race and ethnic groups and educational levels cited safety as one of the top challenges that needs to be addressed. Within each neighborhood, however, concerns of safety varied. Of all residents in Burr Oaks who mentioned crime and disturbances as something they did not like about their neighborhood, 79% resided on two of the ten Burr Oaks research blocks. Similarly, of all residents in Bram’s Addition who mentioned crime and disturbances as something they did not like about their neighborhood, 64% resided on two of the Bram’s Addition blocks that were closer to the drug houses.

A few residents mentioned that South Madison’s image may be playing a role in terms of encouraging crime. They believed that negative images make their neighborhoods seem like a permissible atmosphere for illicit activities. This gives people an excuse to come to their neighborhoods to “hang out and sell drugs.” Furthermore, a lack of respect for the community makes it so “it's ok to trash it or steal from it because it’s the Southside; outsiders keep driving in and think it’s ok to trash our community.” Ultimately, residents believe a better image would discourage people from engaging in illicit activities.

A few other residents mentioned that their neighborhoods were safe and calm and that South Madison’s reputation of having a high crime rate was more a perception than reality. According to one respondent, “I heard the area had crime, but I haven't seen any yet.” Another shared that there is a “misconception of drugs and crime. People think it’s a bad place, and residents don't care.”

B. Physical aspects

1. Accessibility to neighborhood amenities and work

The neighborhoods’ location, its accessibility to local and citywide amenities and employment, was a key reason that homeowners and tenants moved and stayed.

Neighborhood Amenities: Residents liked that amenities were close by and “everything is in walking distance.” They also appreciated that the neighborhoods were centrally located, close to downtown and to other parts of the City. As one resident mentioned “great location, convenience to everywhere.” Neighborhood amenities included resources and services such as churches, schools, library, bike paths, parks, restaurants, and shops.

More homeowners and tenants in Bram’s Addition (36%) mentioned that they liked the accessibility to neighborhood amenities than homeowners and tenants in Burr Oaks (28%). As one homeowner commented, “it's accessible for bikes and buses, there is a community garden, for kids there are parks, and the library is within walking distance.” The research team found the difference in neighborhood response to be an interesting finding and given their similarity in distance to other areas of greater Madison, they wondered if it had to do with the amenities specific to each neighborhood. Though residents of different cultural and racial backgrounds mentioned liking the accessibility to neighborhood amenities, it was mentioned more by Whites (41%) than by those of other cultural and racial backgrounds combined (25%).

Some residents mentioned the need for more public spaces, businesses, and services. For example, though some residents liked their neighborhoods because there were places for kids to play, other residents said that there were not enough activities for youth. Residents expressed that the area needed to have more organized activities and places for kids to go, such as a neighborhood center that can offer youth programs, exercise classes, and community gathering spaces. A few residents mentioned that more shops of a specific type would be helpful. One person said, “there is everything I need, but a big grocery store.” Also, a person mentioned that smaller businesses close by, such as a coffee shop, could encourage people to spend more time together and “eat, play, and buy things.”

Work: Location is important in terms of neighborhood amenities, but also in terms of commuting distance to work. More than 60% of residents said that it took them 15 minutes or less to get to work (Figure 2.1). Several residents commented that they moved to the neighborhoods or continued living in the area because they wanted to be close to work.

An interesting finding was that even though public transportation is accessible on nearby Park Street, over 70% of respondents said that they used a car to commute to work (Figure 2.2). As shown in Table 2.1, this is similar to that found for Town and City of Madison residents. Some residents volunteered the importance of moving to or living in these neighborhoods because they could walk if needed or easily access the bike paths and bike to work. As stated by one resident, “I can walk to where needed or bike; things are close by.”

Figure 2.1: Commute time to work

Figure 2.2: Main mode of transportation used by residents

|

Table 2.1 Comparison

of commuting information for Bram’s Addition, Burr Oaks,

Town of Madison, and City of Madison* |

||||

|

|

Bram’s Addition |

Burr Oaks |

Town of Madison |

City of Madison |

|

Travel time to work less than 30 minutes |

84% |

78% |

79% |

85% |

|

Mode of Transportation -Car,

Truck, Van |

75% 7% 3% 11% |

82% 12% 2% 3% |

73% 17% 3% 3% |

68% 12% 0% 20% |

| * Information from 2000 census | ||||

Community members believed that not only is distance to work important, but also it is vital to create local employment opportunities. Some neighbors believed that a variety of employment opportunities that would be able to sustain a diverse workforce should be more easily accessible. A few residents mentioned that more small businesses would increase the number of jobs in the neighborhoods, which they felt were lacking.

2. Affordable housing

Residents stated that available housing that they can afford was an important reason they moved to these neighborhoods. This was stated more by homeowners (36%) than tenants (19%) and slightly more by residents in Burr Oaks (34%) than in Bram’s Addition (27%). Respondents, who had lived in the neighborhoods for less than 5 years, were more likely to mention that they moved here because of affordable housing than those who were here longer. The research team believed that one reason for this influx of people could be that Madison’s overall housing prices have increased dramatically in the past five years with South Madison remaining one of the few areas that people can still afford.

Residents said they moved here because of the cheaper rent, affordable homes, or the lack of income to move anywhere else. As stated by a few tenants, “[I moved here] because of the price of housing, low rent” and “I found a nice, inexpensive apartment.” A few residents stated that they were looking to buy a home and could not afford to buy anywhere else. As expressed by a few homeowners, “the property values are not as inflated [here]” and “I was looking to buy a house that’s affordable; this was my first house.”

Affordable housing is also a reason residents continue to live in these neighborhoods. Homeowners and tenants ability to afford and maintain their homes will be discussed in more detail in Chapters 3 and 4.

3. Physical maintenance and upkeep

After safety, a common response regarding what residents in Bram’s Addition (22%) and Burr Oaks (18%) neighborhoods did not like about their communities was the lack of physical maintenance and upkeep; this included private homes as well as public spaces. Examples of this include “the creek being smelly and dirty,” drainage problems in the street, some homes being in disrepair, and apartment managers not keeping their property well maintained. More on physical maintenance and upkeep of homes is discussed in Chapters 3 and 4.

Though tenants and homeowners reported that better upkeep of the neighborhood and physical improvements would make South Madison a better place to live, less than 10% of residents believed that it is a top issue facing the South Madison community that needs to be addressed.

This current section presents residents’ viewpoints on the positive attributes and challenges of their neighborhoods. The research team was also interested in understanding what residents’ viewpoints were regarding the revitalization efforts that are underway and how they believe it will eventually impact the community. The next section shares residents’ views about how these efforts will affect them and their neighborhoods.

|

Table 2.2 Characteristics residents liked about their neighborhoods (n =

109) |

||||

|

Neighborhood characteristics |

Homeowners |

Tenant |

Bram’s Addition |

Burr Oaks

|

|

Sense

of community |

53% |

54% |

56% |

50% |

|

Accessibility/amenities |

35% |

27% |

36% |

28% |

|

Diversity |

13% |

16% |

14% |

14% |

|

Personal/cultural

ties |

11% |

3% |

12% |

4% |

|

Affordable/adequate housing |

8%* |

0%* |

7% |

4% |

|

* Differences between column values are statistically significant at the p<.10 level using a Chi² test. |

||||

|

Table 2.3 Reasons residents moved in and stayed in their neighborhoods (n=109) |

||||

|

|

Why did you move here? |

Why do you continue living here?

|

||

|

Neighborhood

characteristics |

Homeowners |

Tenants |

Homeowners |

Tenants |

|

Sense

of community |

14% |

19% |

32% |

54% |

|

Accessibility/neighborhood amenities |

38% |

16% |

27% |

24% |

|

Affordable/adequate housing |

36% |

19% |

18% |

16% |

|

Personal/cultural

ties |

35% |

33% |

17% |

22% |

|

Diversity |

7% |

0% |

6% |

5% |

|

Table 2.4 Characteristics residents did not like about their neighborhoods (n =

109) |

||||

|

Neighborhood Characteristics |

Homeowners |

Tenants |

Bram’s Addition |

Burr Oaks

|

|

Community

relations |

18% |

16% |

25%* |

8%* |

|

Cost,

mix, type of housing |

10%* |

0%* |

5% |

8% |

|

Safety |

53% |

52% |

49% |

56% |

|

Lack of physical maintenance/upkeep (public space and private property) |

26% |

8% |

22% |

18% |

|

Lack and dislike of neighborhood amenities, resources, and businesses |

10% |

8% |

8% |

10% |

|

No

particular problems |

10% |

19% |

14% |

12% |

|

* Differences between column values are statistically significant at the p<.10 level using a Chi² test. |

||||

|

Table 2.5 Top issues faced by the South Madison community (n =

109) |

||||

|

Neighborhood characteristics |

Homeowners |

Tenants |

Bram’s Addition |

Burr Oaks

|

|

Community

relations |

16% |

19% |

22% |

12% |

|

Economic

development (i.e.

lack of employment and businesses) |

35%* |

19%* |

29% |

30% |

|

Safety/neighborhood disturbances |

53% |

62% |

58% |

54% |

|

Affordable/adequate housing |

13% |

8% |

12% |

10% |

|

Upkeep/maintenance |

6% |

5% |

3% |

8% |

|

*

Differences between column values are statistically significant

at the p<.10 level using a Chi² test. |

||||

III. Revitalization and its possible consequences

Revitalization works to increase community well-being through efforts that focus on land use, transportation, urban design, and economic and community development. There are several plans to improve the Park Street corridor and the surrounding neighborhoods that include restoring Wingra Creek, building a water spray park in the Burr Oaks neighborhood, and improving bicycle and pedestrian safety on Park Street. They also include the redevelopment of the Villager that is a currently a complex of health and social service providers with some retail. The Villager redevelopment includes retaining the health and social service providers, changing the mix of businesses and increasing retail, developing housing, creating a community gathering space, and expanding the current library.

Local residents are involved in the revitalization in numerous ways from planting perennials in the Park Street median to being active members of local efforts such as Park Street Partners. Park Street Partners is a collaboration among area residents, hospitals, businesses, governmental agencies, and the university dedicated to the economic and physical revitalization of the Park Street corridor.

The revitalization of Park Street and the South Madison neighborhoods has been an ongoing issue. The research team thought it was important to learn the community’s viewpoint on this redevelopment, most specifically how revitalization will affect the housing situation and the neighborhoods surrounding Park Street. The research team also wanted to investigate whether or not the outreach efforts to initiate understanding of and participation in the revitalization process have been successful.

Twenty-eight percent of homeowners and 63% of tenants stated they did not know about the revitalization or they had no response to the question “Do you know about the revitalization plans in South Madison?” (Table 2.6) There was also a significant difference between neighborhoods. Whereas 53% of Burr Oaks residents interviewed did not know about or they had no response to the revitalization question, only 29% of Bram’s Addition residents did not know about or they had no response. Whether or not residents’ knew about revitalization did not vary based on the length of time they had lived in South Madison.

Residents who believed that revitalization would be positive for the community believed that the revitalization efforts would attract more businesses and jobs to the area; thus, there will be more people spending money in the neighborhood. As one resident mentioned, “more money will be spent in the community, [could have a] second job closer to home.” A few people liked that revitalization may increase their property value or improve South Madison’s image. As said by one resident, who was optimistic about revitalization, “…it is likely to raise the value of my house!”

Although residents believed there was a positive side to revitalization, there were also concerns about some possible negative consequences. There were residents who felt positive, but had some reservations. These residents believed that revitalization will increase the number of businesses, but it will also increase housing costs, including taxes and rent, making the neighborhoods less affordable. One resident said, “My hope is that the improvements to Park Street and Quann Park, etc. will make it a more comfortable place to live. I worry that housing costs will rise causing development that will eliminate the smaller homes.” Or as another respondent said, “better retail and business, but rent may become less affordable.”

The majority of those who felt negative about the impact of revitalization believed that housing costs would increase, thus, forcing people to leave the area. Many homeowners stated that “taxes would go up.” As expressed by one homeowner, “poor people will have to leave, where will they go?” This is of particular concern since one of the major reasons residents moved to and stay in the area is availability of affordable housing.

|

Table 2.6 Possible effects from revitalization (n =

109) |

||||

|

Possible Effects |

Homeowners** |

Tenants** |

Bram’s Addition |

Burr Oaks

|

|

Positive |

31% |

20% |

32% |

21% |

|

Positive with reservations |

18% |

3% |

11% |

15% |

|

Negative |

16% |

6% |

18% |

6% |

|

No effects |

7% |

9% |

11% |

4% |

|

Don’t know about revitalization or possible effects (or no response) |

28% |

63% |

29% |

53% |

| **The differences between homeowners and tenants are statistically significant at the p<.05 level using a Chi² test. | ||||

In summary, the positive views of revitalization include development of businesses, more employment opportunities, improved image of the neighborhoods, higher property values, and better public amenities. The negative views focused on the increase in housing prices and taxes that may drive some residents, especially low-income and the elderly, out of the neighborhoods. These tensions reflect outcomes that have occurred in other parts of the country where revitalization has happened. To enhance the positive outcomes and minimize the possible negative consequences from revitalization, this tension needs to be considered and addressed.

IV. Suggestions for the neighborhoods

Bram’s Addition and Burr Oaks neighborhoods include qualities that Jane Jacobs (1961), New Urbanists, and many others believe contribute to the production of good and livable communities. These qualities, which are also found in the study area, include different types of housing (price, size, layout, ownership), a multi-use area (residential as well as retail), human scaled streets (short blocks in the neighborhood with sidewalks), and nearby amenities and public spaces (stores, restaurants, social services, and parks).

When the community residents answered questions about their neighborhoods, they weren’t thinking about Jane Jacobs or the principles of urban planning; they were sharing their own personal reasons for liking their neighborhoods. Residents stated that the qualities they appreciate about their neighborhoods are sense of community and good neighbors, shared personal and cultural background and diversity, access to neighborhood amenities and work, and affordable housing.

Residents had many wonderful comments about their community, but they also had concerns that need to be addressed to improve the livability of the area. The following suggestions arose during resident’ interviews and are from the research team’s findings. Their purpose is to support and enhance the positive attributes of the neighborhoods, while addressing the challenges that are negatively impacting the area.

For additional information regarding community viewpoints in the Burr Oaks and Bram’s Additions neighborhoods, it would be beneficial to also review South Madison Anti-Drug Coalition’s report titled Community Climate Assessment (2004).

Improve community relations

Sponsor more activities that increase communication and build relationships.

Many residents wanted to increase communication and build relationships with their neighbors. They believed this could increase respect and reduce prejudice, but also the increase in community presence could decrease illicit activity. Activities could include community suppers, block parties or festivals, and increasing resident involvement in decisions that affect their neighborhoods. One idea was to strengthen the neighborhood associations so that they are in a better position to bring residents together and sponsor more neighborhood activities. The inclusion of pictures and stories from the events could be shared in the broader Madison media to give others the opportunity to experience the positive qualities of South Madison.

Build shared leadership and collective ownership of public issues. Create conditions where local residents of all ages and backgrounds can see their own role and personal and social value in participating in the betterment of the community. Together they develop shared leadership and ownership of community problems and solutions.

Increase opportunities for leaders from different backgrounds to connect with each other, network, and build collaborations. Organizations and community groups outside South Madison could also be a tremendous resource; for example, East Isthmus Neighborhood Planning Council had a workshop where people from around Madison exchanged ideas and networked regarding their newsletters. Existing programs should be utilized to build and nurture leadership ability in individuals and teach skills. There are many training programs offered by different organizations throughout Madison (e.g. Grassroots Leadership College, Community Organizing and Family Issues). Existing leadership models and skill training programs throughout the country should also be reviewed and relationships should be built to continually enhance what is happening in Madison.

Increase safety

Improve communication and collaboration between police officers and residents. Community residents mentioned wanting to increase collaboration and understanding between police and neighbors so they can work together to solve problems. This request from the neighbors fits well with the concepts in the Problem-Oriented Policing model that is being promoted by the Bram’s Addition and Burr Oaks Neighborhood Officers to build community and increase safety. Problem-Oriented Policing “…places a high value on new responses that are preventive in nature, that are not dependent on the use of the criminal justice system, and that engage other public agencies, the community and the private sector when their involvement has the potential for significantly contributing to the reduction of the problem.”41

Currently, steps have been taken towards building these bridges. South Madison neighborhood organizations have planned community tours of the 9-1-1 emergency call center where local residents can learn about the center and educate the police and dispatchers about their concerns. The program should be reviewed to see how the lessons learned can be shared on a broader basis and if more tours should be held.

Increase pedestrian safety. Residents believe that cars drive too fast through neighborhood streets and are endangering children. One suggestion to increase pedestrian safety was to place speed bumps on the street to slow traffic; however, this is not always effective. Another option would be for local groups to work with the Safe Community Coalition of Madison and Dane County to learn about their programs and how they have worked with neighborhood groups to increase pedestrian safety.

Improve South Madison’s image. Residents believed that improving South Madison’s image is useful in building connections among community members and it may also discourage people from illicit activities, such as drug dealing. There should be an increase in positive coverage in Madison media regarding the people, organizations, development, and happenings in the community. South Madison media (e.g. Southern Exposure, neighborhood newsletters) should continue their work and find ways to connect with each other and build collaboration. Madison Commons, a program that teaches community members journalism skills, should be utilized by local residents with articles being posted on the website and used in other media venues.

Increase amenities and economic development

Assess neighborhood programs and resources. Residents stated that programs were lacking for youth, seniors, and immigrants. In addition, they also stressed the importance of a learning facility for adults and seniors. To effectively implement this concern, there should be an assessment of the neighborhood programs, resources, and services already in the area to evaluate what is missing, what needs to be changed, what requires more publicity, and what should be integrated. Before an assessment of this magnitude is undertaken, current resource surveys should be compiled and made available so as not to duplicate previous work (e.g. Madison Area Technical College survey, survey on work force housing).

Increase number and variety of employment opportunities available in the area to support the diverse workforce. According to community residents, this includes developing larger operations and encouraging local small and diverse businesses (e.g. family restaurant, coffee shop, grocery store). These businesses would be diverse in product or service offered, but also in ownership and employment opportunities. Residents believed that more local businesses would allow residents to walk to shops, increase job opportunities, and improve community relations by having places people could gather.

Improve physical maintenance and upkeep

Assess and increase use of current information and programs. Community members were concerned about the physical appearance of private homes as well as public spaces. There should be an assessment and compilation of current information regarding who to contact in specific situations and what are the standards and regulations. Programs offering home repair assistance should be compiled and connected with a South Madison liaison that connects residents with programs. For example, Project Home’s Hammer with a Heart brings together volunteers from the community to assist homeowners who are low-income with their necessary repairs. All of this information should be made accessible through a website, neighborhood newsletters, and binders located at the South Madison Branch Library and other locations. Another way to improve the condition of the neighborhood, which will also build relationships, is to have more resident planned and implemented local clean-ups, such as the existing Earth Day clean-ups.

Increase knowledge and involvement in revitalization plans

Improve outreach and engagement regarding revitalization. Specifics regarding the revitalization of Park Street were not known by the whole community, especially tenants. Outreach and a community feedback process need to be designed and implemented so they engage the different members of this diverse community. Relationships should be built with community leaders who can motivate others to participate and share with planners and organizers the most effective methods to increase involvement.

As shown in the findings, residents expressed advantages as well as disadvantages to revitalization and believe this tension needs to be addressed to ascertain the best outcome for the community. Park Street Partners should continue its work of being a steward of the Park Street vision and look to increase its connections to the South Madison community.

Ensure quality housing that is affordable in the community

Ensure that quality and affordable housing is available in South Madison. Being able to afford the purchase of a home or rent was a major reason respondents moved to the area and is an essential aspect of a healthy living situation. As stated in Chapter 1, a housing unit is defined as affordable if it costs no more than 30% of an individual’s or household’s gross income.42 However, this definition does not include repairs and maintenance for homeowners that can be very costly and make a current housing situation no longer part of a sustainable budget.

It is vital that land and housing acquisitions are implemented soon before prices increase to the point of not being fiscally permissible for non-profits and others to preserve existing, rehabilitate substandard, and create opportunities for different types of affordable housing in South Madison. There should be an organization that coordinates the affordable housing situation in South Madison. They would ensure that an overall vision is designed and implemented, while coordinating the various stakeholders. In addition, a university student could do research on innovative projects taking place throughout the community where affordable housing plays an important role in mixed-income neighborhoods.

It is also important that those working on the affordable housing issue in South Madison connect with other organizations focusing on this topic. Such involvement could help ensure that there is quality housing for individuals who are low-income in South Madison, but also that affordable housing is distributed throughout the larger Madison community. The ability for homeowners and tenants to afford their specific house will be discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, respectively.

Chapter 3: Homeowners

This chapter shares information regarding homeowners’ general living situation, home buying process, home maintenance, advantages and disadvantages of ownership, and suggestions for improvement. Of the 72 homeowners interviewed, 41 were from the Bram’s Addition neighborhood and 31 were from the Burr Oaks neighborhood. The information on the tenants in these neighborhoods is presented in Chapter 4.43

A. South Madison roots

Though homeowners have lived in South Madison for a variety of years, more than half have lived in South Madison for over 11 years (Table 1.2). One long time resident, who had lived in the neighborhood for over 30 years and had raised his family there, invited the research team members to sit on his stoop. It was a pleasant summer evening – not too hot and not too humid. Passers-by, both old and young, waved and honked their horns at our interviewee. Without even asking, it was clear that this resident had roots in this neighborhood and had been living there for many years. He described some of his neighbors – most had been his neighbors for over 20 years. Even though new people are always moving into the neighborhood, there are many residents like this homeowner who have established roots. When the research team asked homeowners how long they have owned their current home, as many as 40% had owned their homes for more than 11 years (Figure 3.1).

All homeowners, no matter how many years they had already lived in the area, shared that stability was important to them. Homeowners were asked, “How long do you plan to live in your home?” Almost two-thirds (62%) commented that they were planning to be in their home for the long-term (more than 6 years), 20% said the medium-term (between 2 and 6 years), and only 9% expected to be there for the short-term (less than 2 years) (Figure 3.2). Many who said they planned on living in their home for the long-term said they expected to be in their home “forever” or had no intentions of moving.

Figure 3.1: Length of time homeowners have owned their homes

Furthermore,

those who expected to be there for the long-term represented

homeowners who had lived in their home for different periods of time.

One would expect that the longer a homeowner lives in their home,

the more committed they are to staying in their home for the

long-term. However, the data reveals that homeowners who had lived

in their homes for more than one year expressed the same level of

commitment to staying in their homes for the long-term. For example,

those living in their homes between 1 to 4 years expressed the same

level of commitment as those living in their homes between 11 to 20

years.44

Residents’ level of commitment greatly increased for those who

have lived in their homes for more than one year.

Figure 3.2: Time planning to live in their homes

B. Homeowners’ living situation

A homeowner’s living situation includes information about the physical space (number of bedrooms), household composition, and their housing costs.

Physical space

Only a few homeowners (3%) lived in a 1 bedroom residence. The majority of homeowners lived in dwellings that had 2 or more bedrooms. Twenty five percent of homeowners lived in 2 bedroom homes, while nearly 40% lived in 3 bedrooms homes. The remaining third of homeowners lived in homes of more than 3 bedrooms.

Household composition

Some

homeowners lived by themselves, while others shared their households

with family members, friends, and others (Table 3.1). Most commonly,

homeowners had households of either 2 to 3 people or 4 to 5 people.

Nearly 20% of homeowners lived alone (see Chapter 4 for more

information on tenants).

|

Table 3.1 Number

of household members by

homeowners and tenants |

||

|

|

Homeowners |

Tenants |

|

1 person |

19% |

9% |

|

2 to 3 persons |

40% |

55% |

|

4 to 5 persons |

35% |

21% |

|

6 or more persons |

6% |

15% |

The

living situation of homeowners’ varied by race and ethnicity

(Table 3.2). Though there was some slight variation between Whites

and African Americans,45