http://comm-org.wisc.edu/papers.htm

Cheryl Honey, C.P.P.

Email: wecare@familynetwork.org

Good Neighbors

Frequently Asked Questions

How does Community Weaving Work?

What are Community Weaving Webs of Support?

Weaving the Fabric of Community (outcomes and how it works)

Core Beliefs and Guiding Principles

Community Weaving Change Dynamic

Table of Uses

Getting Started

Grassroots, group and organizational initiatives

Community-wide initiatives

Community Weaver Certification Training

Coalition Building

Family Advocate Recruitment & Training

Coalition Partners

Community Coordinator

Roles, Responsibilities & Relationships

Community Weaver

Good Neighbor

Family Advocate

Partners & Supporters

Community Coordinator

Conditions for Success

Community Readiness

Sustainability

Burning Questions

Theory Base

Final Thoughts

About the Author

Acknowledgement

References

References to Family Support Network

Unless local communal life can be restored, the public cannot adequately resolve its most urgent problem, to find and identify itself.

---John Dewey

Community Weaving emerged from the experiences of a small group of neighbors who created their own social support system. It was sparked by a mother’s desire to meet the needs of her children and thrive. Frustrated by the way local agencies treated her as if she was broken and needed fixing, she gathered her neighbors together and started a social support network. After cutting through a lot of red tape to hold gatherings at a local school, the neighbors invited school parents and staff to participate. Everyone pooled their resources, shared stories and invited speakers from local agencies to address topics impacting their lives. They learned about local resources, developed new skills, and supported one another. This created a synergy that attracted more parents and neighbors from the surrounding area. The families agreed to be Good Neighbors, pool their resources, support one another and abide by the Steps to Excellence. They shared knowledge and resources, taught each other new skills, and did special projects to improve conditions in their community. Over time, they felt like a family.

Everyone made their own unique contribution by, organizing or attending educational and recreational opportunities, and spearheading change initiatives in the community. Good Neighbors wanting to provide one-on-one support to those referred into the network by local agencies were trained as Family Advocates. The group published and distributed a monthly newsletter to keep each other informed of their accomplishments and included a calendar of upcoming activities. The newsletter was posted throughout the community so others could get involved and participate in activities.

In February 1993, the group developed partnerships with organizations in the community, formed a board of directors, and founded a non-profit 501(c) 3 organization called the Family Support Network (FSN). The organization was established to overcome the barriers they encountered as an informal group. The non-profit status transformed the group into a legitimate sustainable entity enabling it to collaborate with other organizations, and receive grants and tax-deductible contributions.

Over the next three years, the Family Support Network (FSN) grew to over 400 Good Neighbors and Family Advocates across five states and was featured in articles on the front page of The Seattle Times on March 2, 1996 and February 8, 1997. This brought national attention to this grassroots effort and Good Neighbors from across the country registered their resources and engaged with neighbors who shared common interests or lived nearby using web-based technology developed by volunteers. Those who did not have access to computers contacted FSN Community Weavers who helped them access resources, activities, trainings and their neighbors.

The individual capacity of the Good Neighbors grew in direct proportion to the human and tangible resources made available by all other Good Neighbors and FSN Partners on the FSN website. Good Neighbors tapped the FSN Resource Treasury for the resources they needed to help themselves and others, and used the network to find jobs, housing, cars and tap into great ideas. Assistance was freely given and the knowledge and insight gained from the experiences transformed FSN volunteers into leaders, pioneers, role models, mentors and change agents in their communities. Many received awards and recognition for their accomplishments and continue to give back to their communities.

How does Community Weaving Work?

The Family Support Networks and experiential learning communities emerge from Community Weaving practices. Partnerships with organizations representing the diversity of the community are established. Partners recruit staff, employees, clients, students, parents and members as participants who pool resources and make their own unique contributions to a collective effort striving for the common good. Everyone has free and easy access to one another, resources and opportunities to engage and serve.

Community Weavers learn Community Weaving practices and principles from Master Weavers who share their stories and teach them how to use the tools, techniques and technology to grow their own social support networks in their schools, churches, neighborhoods, organizations and businesses. Good Neighbors who share similar passions or common interests combine resources and create furniture warehouses, childcare coops, clothing exchanges, and community gardens. Those who enjoy the outdoors and recreational activities organize rafting trips, campouts, ropes courses, barbeques, softball games, paintball competitions, and vision quests. Community improvement projects are organized using FSN technology to spearhead change initiatives, such as shutting down crack houses, responding to disasters, organizing block watches, raising funds for neighborhood beautification and revitalization projects, and starting up new businesses.

Local organizations such as the American Red Cross, Public Health Department, schools, churches, businesses and a variety of civic, social service and youth organizations are recruited as FSN Partners and provide free space for activities, access to speakers and educational materials, as well as free trainings to FSN volunteers. FSN partners train staff as Community Weavers who utilized the resources of the FSN to better meet the needs of their clients.

What are Community Weaving Webs of Support?

Cultivating diverse and meaningful relationships is at the core of Community Weaving. It occurs among individuals, within communities and across states, as the following examples illustrate.

The Emergency Service staff of the Seattle King County American Red Cross placed victims of disasters into the homes of Good Neighbors who were trained as Family Advocates. Child Protective Services (CPS) used FSN volunteers to mentor parents and supervise visitations of children in foster care when there was a shortage of staff to supervise the visits

A local hospital called a Community Weaver instead of Child Protective Services when a single mother abandoned her colicky baby in an Emergency Room because she was overwhelmed and at her wits end. An example of how a web of support is interwoven in this scenario is illustrated by this story. The hospital connects the young mother to a Community Weaver who assesses the situation over the phone. The Community Weaver matches the young mother to an FSN Family Advocate volunteer living nearby who is a retired nurse who loves to garden and is feeling lonely and depressed. The Community Weaver asks her to provide respite care to the single mother by babysitting. This gives the retiree a sense of joy and great satisfaction. While babysitting, she notices the empty lot next to the mother’s home and discovers it is for sale. She taps the FSN Resource Treasury to connect with someone who knows the ins and outs of community gardening, and they approached an agency that writes a grant to purchase the vacant lot and start a community garden. The nurse now is doing what she loves, and the young mother brings her children over to help in the garden and visit with her friend, whom they called Auntie M.

“Operation Safe Havens” is another large-scale Community Weaving illustration that includes four FSN volunteers and local agencies. An FSN volunteer initiates Operation Safe Haven in an effort to provide transitional housing to evacuees displaced by hurricanes Katrina and Rita. The Community Weaver living in Seattle screens the families offering transitional housing and conducts background checks. The Community Weaver living in Austin, Texas works with local shelters and matches evacuees looking for transitional housing with host families in Seattle. Organizations in Austin, such as the Red Cross and Salvation Army, give families the resources needed to cover transportation costs to get to their new homes.

Companies, organizations and associations use Community Weaving to link employees and members together to foster creativity and innovation in a fail-safe environment. This results in increasing individual and community capacity and productivity. The model can be utilized as a system of support that extends beyond the walls of the organization and can serve as an employee/member run assistance program. Engagement and participation increase when people feel valued and have access to resources to take care of their own needs.

These various applications of Community Weaving demonstrate the power of connectivity, level of ingenuity and commitment people are willing to make to serve one another. These are examples of how Community Weaving taps into grassroots initiative and functions interdependently with organizations to foster innovation and manifest good works. All the materials developed for these special projects are made available free of charge on at www.communityweaving.org website. This makes it easy to access the materials and technical support to replicate efforts in other communities to address similar situations.

The data collected about the activities of FSN volunteers provides indicators of accomplishments, self-sufficiency and gaps in services. This information is published in FSN Updates and distributed to leaders at all levels of the community. The updates provide valuable information to base decisions on how to best serve the community. FSN Updates is a tool used to identify administrators, public officials and policymakers who are responsive to the needs of the community.

Weaving the Fabric of Community (outcomes and how it works)

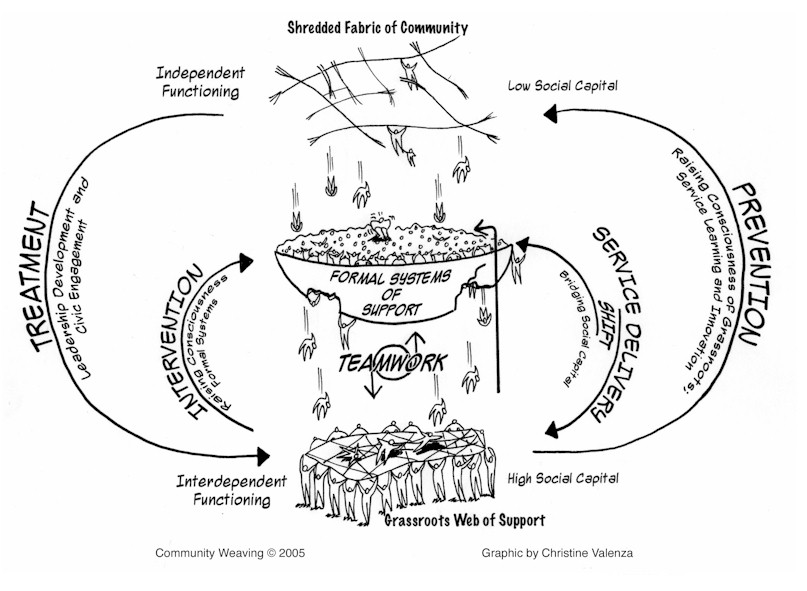

Community Weaving fosters a vibrant grassroots web, which builds and bridges social capital between individuals, among group members and across community systems (Figure 1). The result is an intricate patchwork of conscientious citizens functioning interdependently with one another and formal systems, in order to mend the tears in the social fabric caused by fragmentation and shifts in the cultural, economic and political climate. Given time, the beneficent presence and dynamic activity of Community Weaving changes the culture of community and transform lives.

Community Weavers are the key to building and bridging social capital to weave a grassroots web of support. This new web of volunteers provides a system of support to catch those falling through or out of formal systems. The skills and insights gleaned from serving others raises social consciousness and reweaves the shredded fabric of community. Partnerships between grassroots and formal systems create opportunities for cooperation and teamwork. This interdependent web of relationships instigated by Community Weaving strengthens the social fabric of community and creates space for creativity, innovation, authenticity and living democracy.

The cohesiveness of the community is strengthened as formal systems and the grassroots function interdependently to solve problems impacting the health and welfare of communities. This fosters resiliency to enable individuals, groups, organizations and whole communities to thrive.

The web-based database tracks data detailing the interconnections and interactions. The Community Weavers document the innovations made to improve lives and conditions in the community, as well as the efforts to fill gaps. This information is exchanged among all Community Weavers, enables them to coordinate efforts and compensate for changes by tapping the creative potential of participants and empowering them to solve problems.

Core Beliefs |

Guiding Principles |

|

|

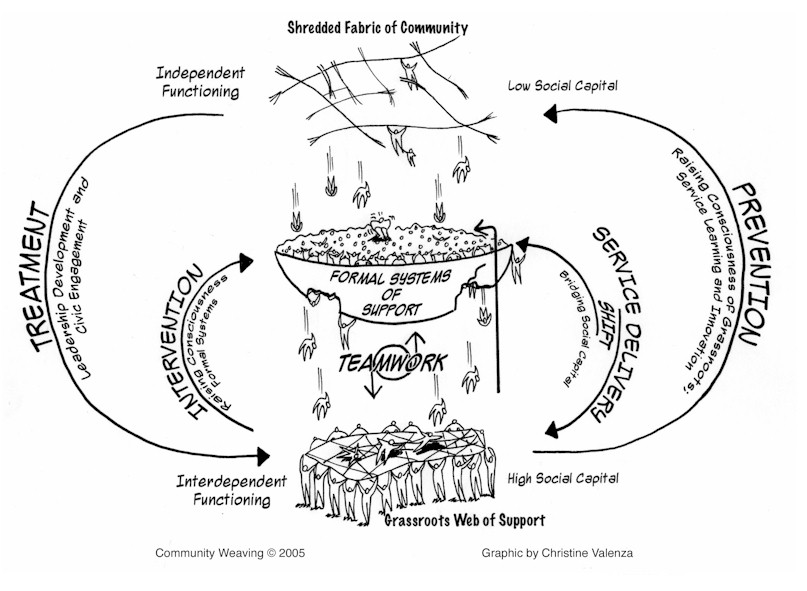

Figure 2. Community Weaving Change Dynamic

Community Weaving Change Dynamic

The change dynamics of Community Weaving (Figure 2) raises consciousness and enhances functioning of individuals and systems by fostering creativity, innovation, and cooperation resulting in an increase in productivity. There are two causes for engagement in Community Weaving. A lower consciousness response is a reactive response to internal needs within the givers or receiver. This is viewed as a lower-consciousness response. Those operating at a higher level of consciousness view challenges as opportunities to initiate change and find satisfaction contributing toward the common good. To improve community functioning and increase levels of productivity, participants experience the process of change through:

Typical Setting |

Time |

Implementation |

Number of Participants |

Community-Wide

|

Month 1

Month 2

Month 4

On-going

Month 5

Month 6

Month 7

On-going

Month 8 On-going On-going

Month 12 |

Phase I

Phase II

Phase III

Phase IV

Phase V

|

|

Typical Setting |

Time |

Implementation |

Number of Participants |

Organization (Single-site)

|

Month 1 Month 4 Month 5 Ongoing Month 6 On-going On-going Month 9 |

|

|

Disaster Preparedness & Response

|

Month 1 Month 2 Month 3 Month 4 On-going |

|

|

Note: Trainings facilitated by Master Weavers who are subcontractors of Excel Strategies, Inc.

Typical Setting |

Time |

Implementation |

Number of Participants |

| Organization (Multiple sites)

Local, national and global

|

Month 1 Month 2 Month 3 Month 4 Month 6 On-going Month 7 On-going On-going Month 12 |

|

|

|

Community Weaving fosters experiential learning communities to enhance the innovative capacity of individuals to affect change in whole systems. An experiential learning community is one that learns continuously and transforms itself. Community Weaving is a whole system learning framework that offers insight on many different levels. Learning occurs through self reflective practice, interactions with others, and new ways of engaging with systems, resulting in shifting social consciousness. A sign of success is when conversations among participants include reflective dialogues to help each other make meaning out of their experience. Community Weaving measures success by increased levels of confidence, self-esteem, initiative, productivity and engagement. When a person is able to correlate their presence in the moment from insights learned from past experience they are more able to recognize opportunities. In fact, they can actually manifest opportunities through recognition of possibilities. Instead of seeing what they need or don’t have, they have a heightened awareness of the presence of what is or what could be. As participants integrate experience with knowledge through dialogue and interactions, it impacts the way they view themselves, view others and view the world. Empathy emerges resulting in the manifestation of possibilities they never knew existed before. This is the ultimate condition for success.

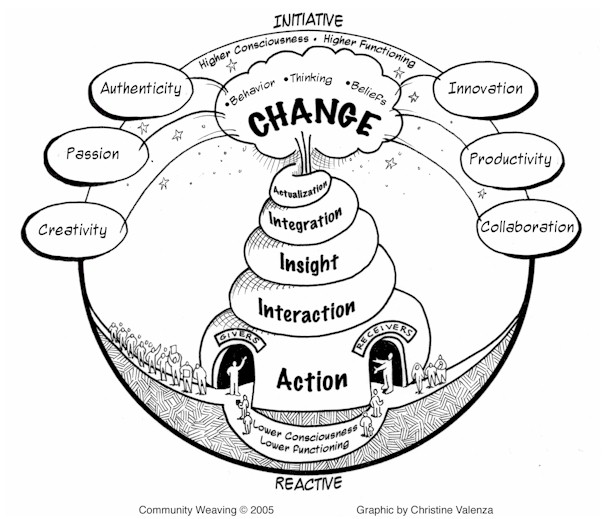

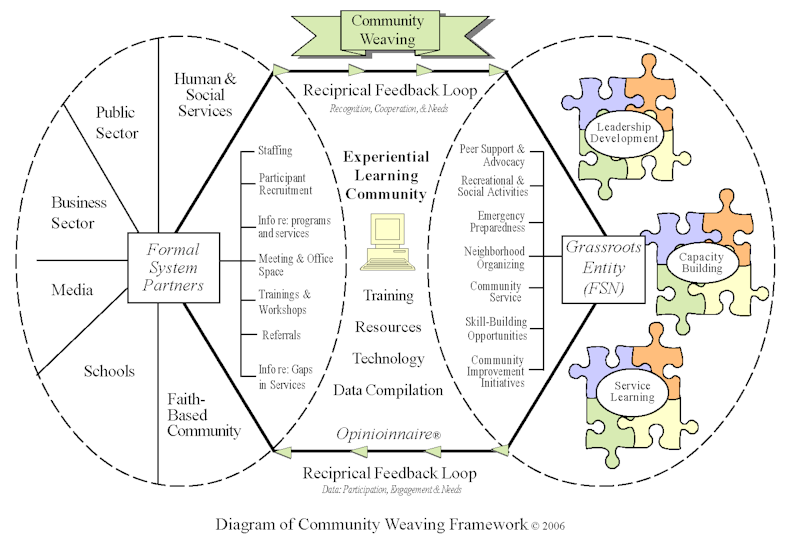

Figure 3. Community Weaving Framework

Grassroots, group and organizational initiatives

Community Weaving is implemented by trained Community Weavers who use the materials, tools and technology to grow individual and group capacity through recruitment of Good Neighbors, tapping their passions, engaging them in service activities and weaving them into an experiential learning community (Figure 3).

Community-wide initiatives

Implementing Community Weaving at the community level can be accomplished in two ways:

Community Weaver Certification Training:

Community Weavers learn the theories and practices that underpin the methodology. Community Weavers learn the dynamics of system change and how to foster conditions to evoke change by employing Community Weaving principles and practices.

Coalition building:

Organizing a collaborative partnership of interested stakeholders who represent the diversity of the community builds a solid foundation that sustains the effort. If a coalition already has experience working on community improvement initiatives, including administrating grants, this is ideal.

Family Advocate Recruitment & Training:

Family Advocates are participants engaging as leaders; role models and mentors who learn skills to provide direct support services in a safe and confidential manner. All Family Advocates must pass background checks.

Coalition Partners:

Coalition members representing various aspects of the community empower Community Weaving by providing financial support and access to resources.

Community Coordinator:

Coordinates implementation of CW initiatives, develops partnerships, and raises community awareness.

Community Weaver

Community Weavers are trained volunteers and staff, representative of the broad spectrum of community who create interconnected social support systems at all levels of community. They recruit, train and engage participants to interact with others in the community (or organization) using web-based technology, and strive to build and bridge social capital across systems.

Good Neighbor

Good Neighbors comprise the majority of participants. They are part of a growing collective of caring citizens, volunteering to serve others and pooling their resources in the Resource Treasury. Good neighbors engage with others in the network and organize social, educational or recreational activities to build relationships and grow social networks. In some circumstances, they commit to volunteering a specified number of service hours in their community.

Family Advocate

Family Advocates are volunteers trained to provide peer support services to those requesting assistance. They are viewed as leaders and change agents in their organizations and communities. They must pass a background check. Commitment to volunteer a specified number of service hours is requested of Family Advocates to satisfy funding requirements.

Partners & Supporters

Partners and Supporters are individuals, community organizations, agencies and businesses who contribute cash, time, expertise, services and equipment. Partners and Supporters are welcome to serve as coalition member in community-wide Community Weaving initiatives.

Community Coordinator

Community Coordinators oversee large-scale implementation and are responsible for administration, public relations, marketing, and building collaborative community partnerships.

Any project or initiative involving change requires preparation, planning and awareness of what to expect and how to negotiate change. Resistance to change is natural and often triggers a response. These responses open gateways for new insights and opportunities. Resistance played an instrumental role in the development of Community Weaving practices. As obstacles were encountered, they were viewed as opportunities to creatively address issues impeding progress. With this in mind, the conditions for success of Community Weaving are:

Communities must be readied to embrace this transformative community-building approach. The keys to community readiness are a desire to change, a willingness to participate, and openness to outcome. Kent Roberts, founder of the Civility Center and author of Community Weaving, offers insight and indicators for community readiness.

If we are serious about improving communities, we must be aware of the local community context and the readiness of that context for change. Even the best strategies will not be successful unless the community environment has a culture of acceptance for new ideas. Conversely, if we have a context of readiness, then anything we do will have a higher probability of success. The correlation between the probability of success and the readiness of the community cannot be over stressed.

In order to assess the readiness of a community, we must determine its ability to confront the conditions that inhibit growth and development. We must ask questions like: Are individuals open to the possibilities of change? What is the relational trust within the community between individuals and its institutions? Do people treat each other with dignity and respect? Where are the opportunities for open, safe and civil dialogue? Can we accept others’ differences and build upon what we share in common? Answers to these questions begin to determine the readiness level of the community. Understanding the concept of readiness is the first step to increasing the collective capital of that community.

Before we start, we must internalize the importance of why we are entering into this complex area of work. We should encourage the community to ask itself: Why must we commit to working together differently? Are things really that much different than in the past? Why can’t we just go our separate ways and still be members of the same community? If a community can’t truthfully answer these questions, it will never succeed. Understanding “the why” is more important than figuring out “the how.” The need to commit to this effort is paramount to the future of the community.

If we want communities and organizations to change their behavior, we must change their context and their readiness level for change. If the contextual culture of the community does not change then nothing really changes. Often we want to implement new ideas but we don’t recognize the level of readiness for them. When our ideas fail, we are discouraged and lose energy. There was nothing wrong with the idea; the community’s level of readiness was not strong enough to support the initiative. As we begin to work together differently, we must recognize the present context and correlate our efforts to fit the degree of readiness for change. You don’t teach a child to run before it can walk. The same principle applies as we start our collective journey in making our communities better places in which to live, learn, work, play and pray.

The burning questions people ask usually are about money and liability. How much does something like this cost? How can it be sustained? Who is liable if someone gets hurt or if property is damaged?

Saving lives is priceless. Initial investment for implementation and training is minimal. The beauty of this approach is existing staff can attend a 3-day training and be certified as Community Weavers to implement the Community Weaving approach in local school, church, business, organization or community. A Community Weaver spends an average of 10 hours a week recruiting, weaving and engaging volunteers using cutting-edge web-based technologies. Due to the wealth of human and tangible resources generated by their activities, the group, organization or company employing them reaps multiple benefits. These benefits include: cross-training and skill-building workshops available to staff and those they serve; a social support system of trained volunteers committed to caring and sharing resources; and a means to self-organize and initiate change initiatives to improve conditions in the workplace and in communities. The result of these benefits increases individual and community capacity, empowers people to act on their own behalf; reduces stress and burnout; and, fosters cooperation, which enhances productivity and improves retention. Community Weaving is sustained as the duties of the Community Weavers are integrated into job descriptions at the various levels of the organization and in diverse community sectors.

The Good Samaritan Law blankets most volunteer activities, as long as there is verbal consent of person receiving services. All participants, whether they are practitioners or receivers, must consent to adhering to policies and procedures, acknowledge the Civility Pledge and agree to release of liability prior to participating in Community Weaving activities.

Theorists Researchers |

Theory |

Key Aspects |

Application |

Outcome |

Margaret |

Self-Organization |

Creating conditions where systems self-organize. |

Creating the space and conditions for self-organizing to occur in many ways on many different levels. |

* Community system reorganization |

David |

Experiential |

Experience as |

Gaining knowledge and experience through interacting with others. |

* Increased knowledge and understanding of self and others. |

Peter Senge |

Learning |

Service combined with learning, adds value to each and transforms both. |

Life-long learning in interactive learning community of people who share common purpose. Dialogues promote inquiry, reflection, & experimentation. |

* Raises awareness of self & others |

Robert Putnam |

Social Capital |

Social interactions build individual and community capacity. |

Engaging participation to create opportunities for civic engagement, social interaction and learning. |

* Individual engagement |

Nan Lin |

Social Networks |

Social networks are fostered by relational ties. |

Creating conditions for social interaction to foster relationships that evolve into social support systems. |

* Face-to-face interactions |

Ken Wilber |

Spiral Dynamics |

Evolution of consciousness. |

Participants experience an increase in understanding of self and their relationship in the world around them. |

* Engage on many different levels |

John McKnight & Jody Kretzman |

Asset-Based Community Development |

Citizen-centered community development based on existence of assets. |

Individual strengths and assets are tapped to grow community capacity and mobilize citizen engagement. |

* Participant driven efforts |

In a time when gauging success is based on measurable outcomes, research is necessary to determine those outcomes. This approach has yet to be scientifically researched to qualify as a best practice and the benefits that come with the distinction.

Special thanks to Kirk Gardner for his devotion as my mentor; John Burbidge for the hours spent editing this chapter; Max M. Stalnaker and Daniel Crawford for the cutting-edge web-based technology, Christine Valenza for her amazing illustrations; Harrison Owen for paving the way to Open Space; and especially Peggy Holman for opening the door to limitless possibility.

Fisher, Robert. (1994). Let the People Decide: Neighborhood Organizing in America, Updated ed. New York. McMillan Publishing

Follett, M. (1920), The New State. New York, NY: Longmans, Green and Co.

Follett. M (1930), Creative Experience, New York. NY: Longsmans, Green and Co.

Granovetter, M. (1982). The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited. P. 105-130 in Social Structure and Network Analysis, edited by Peter V. Marsden and Nan Lin. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Kolb, D.A., Rubin, I.M., and Osland, J. (1991) Organizational Behavior. An Experiential Approach to Human Behavior in Organizations (5th ed.) Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall

Kolb, D.A. (1984) Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NY: Prentice-Hall.

Lin, N. & Cook, K & Burt, R. (2001). Social Capital: Theory and Research. New York, NY: Walter de Gruyter, Inc.

Kretzman, J. & McKnight, J. (1993). Building Communities from the Inside Out. Chicago. IL: ACTA Publications.

McKnight, John (1995). The Careless Society: Community and its Counterfeits. New York: Basic Books/HarperCollins.

McKnight, J. and Kretzman, J. (1996), Guide to Capacity Building. Chicago. IL: ACTA Publications.

Putnam, Robert (1993). Making Democracy Work. Princeton. NJ: Princeton University Press.

Roberts, K. and Newman, J. (2003), Community Weaving, Muscatine, IA: The National Civility Center.

Senge, Peter (1990) The Fifth Discipline: The art and practice of community organizations, New York: Doubleday

The Seattle Times (1996) "A substitute for welfare: Is volunteerism a

better way?" March 2,

http://archives.seattletimes.nwsource.com/cgi-bin/texis.cgi/web/vortex/display?slug=2316872&date=19960302&query=A+substitute+for+welfare%3F+Volunteer+help+a+better+way%3F

The Seattle Times (1997) "Bothell volunteer grew her group into 800

pairs of helping hands" by Jack Broom, February 8,

http://archives.seattletimes.nwsource.com/cgi-bin/texis.cgi/web/vortex/display?slug=2522877&date=19970208&query=Bothell+volunteer+grew+her+group+into+800+pairs+of+helping+hands

Wheatley, M. (2002), Turning to One Another: Simple conversations to restore hope to the future. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers

Wilber, Ken, “An Approach to Integral Psychology,” Journal of Transpersonal Psychology. Vol. 31, No. 2 109-133 (1999)

Community Works: The Revival of Civil Society in America (1998) pg. 81-87

E.J. Dionne Jr. editor

www.brookings.nap.edu/books/0815718675/html/81.html

Beyond Theory: Civil Society in Action by Pam Solo

The Brookings Review, Fall 1997, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 8

http://www.brookings.edu/press/REVIEW/FALL97/SOLO.HTM

“FSN approach recognized as Promising Practice”

Center for Effective Collaboration and Practice

http://www.air.org/cecp/teams/prospectors/bothell_washington_individualized.htm

“Parent’s Leading the Way”

National Family Resource Coalition Publication (1996)

Cheryl Honey, cheryl@communityweaving.com, C.P.P., President, Excel Strategies, Inc. pioneered Community Weaving practices from her grassroots experience growing the Family Support Network, International. She received recognition from the Asset-Based Community Development Institute and the Institute for Civil Society for her innovative approach to building individual and community capacity. Cheryl graduated from Antioch University-Seattle in Transformative Community Building and Human Services. She is a Daily Points of Light Honoree; the recipient of the Giraffe Award; Ambassador for Peace and Excellence in Leadership Awards from the International and Interreligious Federation for World Peace; and 2007 Jefferson Award recipient, http://seattlepi.nwsource.com/local/310305_honey05.html.

Special thanks to Kent Roberts who kindly lent his expertise and the notion of community weaving to this methodology. Kent is the executive director of the National Civility Center. He spent 25 years as a teacher and coach in the public school system and devotes his efforts to community improvement projects. Kent and his colleague Jay Newman, consult with communities around the country developing effective community building approaches and engaging corporations in community improvement projects. They co-authored a community-building handbook entitled Community Weaving.

For more information:

Cheryl Honey, C.P.P. cheryl@familynetwork.org

Family Support Network, International http://www.familynetwork.org

14316 75th Ave. NE

http://www.communityweaving.org

Bothell, WA 98011

(206) 240-2241

“The more resourceful we are among ourselves, the more valuable a resource we become to our families, our communities and our world.”