| COMM-ORG Papers 2004 |

http://comm-org.wisc.edu/papers.htm |

Barri E. Tinkler

August 2004

List of Tables

List of Figures

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Abstract

Chapter 1 Introduction

The Response of Higher Education

Purpose Statement

Research Questions

Chapter 2 Literature Review

The Civic Mission of Higher Education

Community-Based Research

Foundations of Community-Based Research

What is Community-Based Research?

Criticisms and Concerns

Benefits

Collaboration

Chapter 3 Research Methods

Methodologic Framework

Types of Case Studies

Methodology of Community-Based Research

Participants and Setting

Data Collection

Observations

Interviews

Documents

Data Analysis

Analytic Framework

Analysis of Contrasting Cases

Validity

Subjectivity

Limitations of This Study

Summary

Chapter 4 The Coalition for Schools

Case Description

Within-Case Analysis

Community

Collaboration

Power

Trust

Communication

Lack of Consideration

Knowledge Creation

Shared Goals

Views About Data

Valuing Knowledge

Timelines

Unrealistic Expectations

Change

Was This CBR?

Implications for the Field of CBR

Chapter 5 Communities in Transition

Case Description

Within-Case Analysis

Community

Collaboration

Roles and Responsibilities

Communication

Trust

Consideration

Knowledge Creation

Shared Goals

Views About Data

Valuing Knowledge

Timelines

Unmet Expectations

Change

Was This CBR?

Implications for the Field of CBR

Chapter 6 Cross-Case Analysis and Interpretation

Cross-Case Analysis

Community

Collaboration

Knowledge Creation

Change

Continuum of CBR

Findings

Issues Arising From Collaboration in CBR

Factors That Facilitate or Hinder Collaboration

Benefits of CBR

Conceptual Model of CBR

Implications of this Study

Recommendations for Further Research

Conclusion

Notes

References

Appendices

Appendix A: List of Meetings and Interviews

Appendix B: Interview Protocols

Appendix C: Document From First Case Study

Appendix D: Documents From Second Case Study

Table 2: Contrasting Cases of CBR

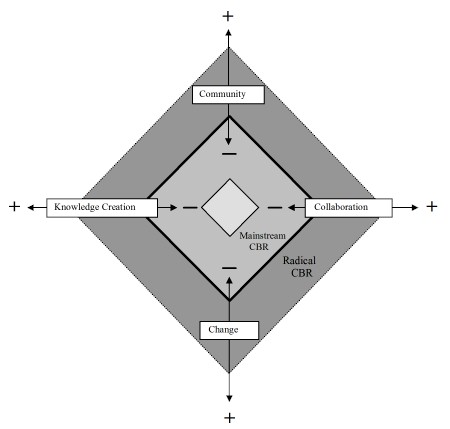

Figure 1: Four Constructs of CBR

Figure 3: Conceptual Model of CBR

First and foremost, I would like to thank my husband Alan Tinkler for his tireless support throughout this process. Through dialogue, he helped me to develop and solidify my findings, and he assisted in developing the conceptual model that I present in this dissertation. He also provided continuous, important editorial advice starting with the proposal and working through the final product. Alan, my family (parents, siblings, nieces, and nephews), and coworkers (Anna Parish-Carmean and Christy Moroye) also provided moral support and continued encouragement as I worked through this process. I would not have made it to this point without all of their support.

I would also like to thank my advisor and dissertation chair, Dr. Nicholas Cutforth. Dr. Cutforth introduced me to community-based research, and I thank him for helping me to find a research venue that is meaningful for me. His passion for this work is contagious. I also thank him for his kindness, support, and consistent thoughtful and timely feedback. His encouragement throughout this process helped me to stick with this project at times when I was wavering.

One of my committee members, Dr. Gary Lichtenstein, also played a significant role as I worked through both of the community-based research projects described in this study. I appreciate the extensive expertise that Dr. Lichtenstein made available to me throughout this work, and I appreciate the contributions that he provided to my thinking about the field of CBR. I would also like to thank another committee member, Dr. Jennifer Whitcomb, for both her support as a colleague and as a friend, as well as her advice in relation to case study design. Her expertise was important in helping determine the structure of my dissertation.

My other committee members also played important roles in this process. Dr. Bruce Uhrmacher assisted in helping me define the topic of my research and in developing my research questions. Dr. Ginger Maloney provided important feedback during both the proposal process and with the final dissertation in challenging me to examine the subjectivities that I carried into this work. Her feedback was important in encouraging me to explore these issues with greater depth. I would also like to thank Dr. Jean East for chairing my oral defense. She added thoughtful contributions to the discussion.

There were several people who provided important information as I was conducting my CBR work. I would like to thank Dr. Randy Stoecker for his advice as well as for the important contributions his writing has had in influencing my views about CBR. There were a number of other people who played important roles in providing information as I completed each CBR project, including: Ethan Hemming, Mike Kromrey, Matt Sura, Luis Ibanez, and Carol Dawson. I would also like to thank my community partners in both CBR projects for their willingness to pursue this work and for allowing me to study my work with them.

Barri Tinkler is an assistant professor in the Department of Secondary Education at Towson University in Towson, Maryland. She has completed a number of community-based research projects, many of which focus on working with immigrant populations. Her research interests include: community-based research, minority parent involvement, and case methods in teacher education.

Traditionally, academic researchers have not involved underserved communities when dealing with and researching difficult social problems. Many universities are now feeling pressure to find ways to work closely with local, disadvantaged communities. Community-based research (CBR) is a new movement in higher education that combines practices from other participatory research models as well as service-learning. CBR requires researchers to work closely with the community to determine a research agenda and to carry out the research to affect change. The goal is to empower disenfranchised and marginalized groups.

The purpose of this study is to explore the process of conducting community-based research from the researcher's perspective. This process study presents contrasting cases of two CBR experiences. One collaboration was conducted with a non-profit educationally oriented organization in a large western city; the other, with community members who provide services to the growing immigrant population in a small, mountain town. The considered issues in both collaborations centered around access to the community, power, communication, shifting research plans, timelines, scope, and the required range of knowledge. There were factors that facilitated or hindered these collaborations-shared goals, defining roles and responsibilities, trust, views about research, rapport, and hidden or fluctuating agendas. Despite these factors, the community benefited from the research process, as did I. The community gained research skills, useful research results, and access to resources. While I gained a sense of purpose, a feeling of engagement, and an expanded knowledge base in relation to research and other peoples.

Based on the findings, I developed a conceptual model organized around the four categories of community, collaboration, knowledge creation, and change. The model presents a way to consider how to increase the value of CBR. In this model, the form of CBR that has the greatest value is radical CBR. Radical CBR requires that the researcher work with grassroots community organizations, share all decision making with community partners, involve community partners in all aspects of the research process, and seek to create change that challenges existing power structures. The model also demonstrates how to add value to more mainstream versions of CBR.

Traditionally, there has been a divide between academic research and the needs of communities beset by poverty. Researchers generally carry out research agendas that are influenced by academic disciplines (Ansley & Gaventa, 1997; Greenwood & Levin, 2000) or established within university departments (Checkoway, 2001). Researchers who pursue an agenda that is determined by academic disciplines seek to fill in gaps in the knowledge base to further that particular field of research. As a result, much of the research that is produced is only of interest to a select few within a discipline and rarely of interest to those outside of higher education and the academic arena (Sclove, Scammell, & Holland, 1998). As Robinson (2000) points out, "Too much academic research is focused on advancing knowledge within the discipline itself, and too little is focused on advancing 'social knowledge,' or on how to find practical solutions to social problems" (Introduction section, para. 2). Nyden, Figert, Shibley, and Burrows (1997) introduce the idea of "opposing orientations to research" (p. 3), specifically research that is designed for empowerment versus research that is created to further an academic discipline. These opposing orientations have created a gap between academics and community leaders who otherwise may work together.

In 1988, faculty and students from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign took on a project that involved architecture, landscape architecture, and urban planning working together to revitalize East St. Louis (Reardon, 1995). Two years later, the project team conducted 40 interviews with community leaders in East St. Louis to determine the impact of the project. Responses to the interviews include: "The last damn thing we need is another academic study telling us what any sixth grader in town already knows. Hell, just send us the money and we will take care of our own problems"; "There's not a single improvement that has been made in East St. Louis that came from the efforts of one of these university consultants" (Reardon, 1995, p. 49). These attitudes were partially a response to past experiences that community leaders had with researchers who ignored the knowledge of local residents and business people in relation to the community. Community members also questioned the researchers' commitment to working with the community to carry out proposals the researchers recommended. Finally, the community viewed the researchers as "carpetbaggers" using the community's problems to justify research grants that did not in turn help the community. Based on the insights gleaned from these interviews, the faculty at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign reorganized their efforts into a participatory research process in which the community became a partner in research, planning, and decision making. The project has since received numerous awards for its achievements in grassroots community development efforts (Reardon, 1995). This effort is an example of how the gap between university researchers and communities can be overcome to affect change.

Though some researchers conducting traditional academic research believe that the information they produce will lead to change, generally change is only incremental (Greenwood & Levin, 2000), and it may not be change that benefits underserved communities. As Stoecker (2002a) says, "Being truly useful, and part of real social change, is something too few of us academics get to experience on a regular basis" (p. 2). The resulting disconnect occurs when researchers write studies in inaccessible "academic" language, publish these studies in obscure journals (Sclove, Scammell, & Holland, 1998), and then expect those who need the information to find the information and utilize it. Porpora (1999) calls this "trickle down academics" (p. 123); the idea that knowledge and research will eventually make its way down to the people who need it. Porpora argues that higher education needs to move away from the "production of knowledge that serves society's elites and more toward the production of knowledge that might serve the downtrodden" (p. 122). Nyden et al. (1997) see collaborative, community-based research as a way to "provide a bridge between the more obscure parts of academic research and the practical questions under study" (p. 7), otherwise the research that academics create, which in fact can be relevant to dealing with social problems, may never be utilized and will "continue to gather dust on library shelves, read only by a few graduate students collecting more references for their dissertation bibliographies" (Nyden et al., 1997, p. 7).

Some researchers make the assumption that good research will lead to enhanced practice for everyone, including the underserved and disenfranchised; yet, it is up to those who need to improve their practice to seek out research findings and determine how to apply these findings (Whyte, 1991). Though researchers generally have good intentions, the reality is that traditional academic research brings about change slowly, if at all. In order for research to affect change within communities, there needs to be a mechanism to connect research to action (Whyte, 1991). By creating a closer link between research and action, research can have a greater impact on local communities.

Community-based research establishes this link between research and action, since the purpose of community-based research focuses not on developing knowledge within a discipline but on creating knowledge that "contributes to making a concrete and constructive difference in the world" (Sclove, 1997, p. 542). In order for community-based research to truly become part of the agenda of higher education, particularly the research agenda, academics need to broaden traditional ideas of research and knowledge (Willms, 1997). As Willms says, "Research should be understood as a process of rediscovering and recreating personal and social realities" (p. 7). Therefore, research is not just about creating knowledge for the purpose of expanding academic disciplines but also about allowing individuals to understand their own realities. Though traditional academic research may allow for academicians to pursue this kind of intellectual endeavor, community-based research creates opportunities for marginalized individuals to better understand their own realities and seek to recreate those realities in ways that will benefit them.

The Response of Higher Education

In order to address the disconnect that exists between academic institutions and the communities in which they reside, many institutions of higher education are gradually becoming more involved with their communities (Maurrasse, 2001; Stoecker, 2001; Strand, Marullo, Cutforth, Stoecker, & Donohue, 2003a; Ward, 2003). As Maurrasse (2001) says, "A movement is emerging" (p. 1). This movement is primarily driven by three factors (Strand, Marullo, Cutforth, Stoecker, & Donohue, 2003b): criticism of higher education in relation to insensitivity to solving social problems in surrounding communities, the "perception that the intellectual work of the professorate is unnecessarily narrow and largely irrelevant to societal concerns" (p. 5), and the concern that students are not prepared to participate in civic life because they are not engaged with the community or with learning.

A number of universities have begun implementing service-learning programs or other service related activities to address these concerns (Chopyak & Levesque, 2002; Stanton, Giles, & Cruz, 1999). Though service-learning has the potential to provide resources to the community, its goal is typically service, not change (Stoecker, 2001; Strand et al., 2003a). In fact, some critical theorists have expressed concern that the service-learning paradigm can be oppressive to those being served and may actually reify the status quo (Maybach, 1996). Robinson (2000) has gone as far as describing service-learning as "a glorified welfare system" (Service Learning as Charity section, para. 2). Though this seems a harsh criticism of service-learning, the reality is that service-learning programs, though they may impact students in positive ways, generally do not provide sustainable change for communities (Maybach, 1996).

Marullo and Edwards (2000) have delineated two strands of service-learning: charity service-learning and service-learning for social justice. They point out that some service-learning activities are really charity, which can be helpful, but they are "moral rather than political acts" (p. 900) that are not change oriented. While Marullo and Edwards do not wish to belittle the value of charity work, they do feel that service-learning should move from a focus on charity to a focus on social justice and social change.

One way that institutions of higher education can provide assistance to communities in ways that have the potential to create sustainable change is through community-based research. Strand et al. (2003a) have defined community-based research, or CBR, as "a partnership of students, faculty, and community members who collaboratively engage in research with the purpose of solving a pressing community problem or effecting social change" (p. 3). According to Stoecker (2003), CBR combines the strategies of action research and service-learning. Stoecker says, "CBR is designed to combine community empowerment with student development, to integrate teaching with research and service, and to combine social change with civic engagement" (p. 35). Community-based research, which has its roots in other forms of participatory research (Stoecker, 2001), may provide the opportunity for academic institutions to become true partners with communities in creating and sustaining change. Chopyak and Levesque (2002) point out that community-based collaborative efforts have increased within the last thirty years. And, as Stoecker (2003) indicates, there is growing interest for the newly emerging model of community-based research that is described by Strand, Marullo, Cutforth, Stoecker, and Donohue (2003a) in Community-Based Research and Higher Education: Principles and Practices.

Strand et al. (2003a) have outlined three guiding principles for community-based research: 1) collaboration, 2) validation of the knowledge of community members and the multiple ways of collecting and distributing information, and 3) "social action and social change for the purpose of achieving social justice" (p. 8). Since community-based research is a collaborative process that validates the knowledge that community members bring (Strand et al., 2003a), the process allows community members to assist in defining problems and determining solutions that are acceptable to them (Stringer, 1999). This process is inherently democratic and allows for the co-creation of knowledge (Greenwood & Levin, 1998). Unlike other kinds of research, with community-based research, the researcher continues to be a part of the process as solutions are enacted in order to assist in facilitating change (Greenwood & Levin, 1998). As Sclove et al. (1998) point out, "Community-based research is not only usable, it is generally used and, more than that, used to good effect" (p. 67).

When considering the three principles of community-based research, Stoecker (2003) sees some variation in the ways these three constructs can be defined, either conservatively or radically. In relation to the construct of collaboration, Stoecker says, "In its most basic sense, 'collaboration' means that researchers and community members should jointly define the research question, choose the research methods, do the research, analyze the data, construct the report, and use the research for social action" (p. 36). Strand et al. (2003a) agree that "ideally, CBR is fully collaborative, with those in the community working with academics-professors and students-at every stage of the research process" (p. 10). Looking at collaboration more conservatively, at the minimum collaboration means "obtaining approval for a researcher-defined project" (Stoecker, 2003, p. 36). Stoecker points out that defining collaboration in a radical way means "placing researcher resources in the hands of grass-roots community members to control, thereby reversing the usual power relationship between the researcher and the researched" (p. 36). Thus this radical construct of collaboration challenges existing power structures in which the community (most often an underserved and disenfranchised entity) is usually the object of others' research, rather than controlling the research from the inception of the research topic to the action that results from the findings.

When considering validation of knowledge, a conservative characterization of this construct would be limited to incorporating community members' knowledge as data (Stoecker, 2003). Viewed more radically it would mean "using community understandings of social issues to define the project and the theories used in it, undermining the power structure that currently places control of knowledge production in the hands of credentialized experts" (Stoecker, 2003, p. 36). Finally, Stoecker also distinguishes both conservative and radical constructs in relation to social change-conservatively change could mean "restructuring an organization or creating a new program" (p. 36) while radically change would mean "massive structural changes in the distribution of power and resources through far-reaching changes in governmental policy, economic practices, or cultural norms" (p. 36). Though Stoecker positions CBR practices as conservative or radical, he is reluctant to create a narrow definition of CBR, as "[a] definition too narrow would exclude too many" (p. 36).

Though there is increasing interest in community-based research, there has been some criticism of these types of research methodologies from members of the academic community. Kemmis and McTaggart (2000) point out that some critics have made the charge that community-based or participatory research confuses "social activism and community development with research" (p. 568). These critics believe that the traditional academic status quo should be maintained. Creswell (2002) mentions that other critics argue that community-based or participatory research is too informal; as a result, the research design may be altered according to the wishes of community partners. There is concern that because of these fluctuations the method is not scientific or rigorous enough. However, as Greenwood and Levin (1998) point out, the fact that community partners play such an integral role in the decision making process leads to more applicable research results for the community.

Some of the criticism of community-based and participatory research may stem from the fact that many researchers in academic settings have not had experience with this kind of research. Since community-based research has been used across disciplines, including sociology, anthropology, communications, and education, the methodology is not specific to one discipline (Greenwood & Levin, 1998). Though community-based research can be useful in many academic fields, the goals and ideals of community-based research could have a significant impact on the field of educational research in helping to seek solutions to the problems plaguing schools today. In fact, Verbeke and Richards (2001) believe that "[c]ollaboration between schools and universities may be the best hope for education reform" (Conclusion section, para. 5), as many educational reform movements are typically unsuccessful.

Educational researchers should collaborate with K-12 schools and with other youth and educationally oriented institutions. As academics become more knowledgeable about and comfortable with community-based research, they will be more willing to embrace it in their own work. Studies that elucidate the process of working on community-based research projects will be useful in encouraging institutions, faculty members, and graduate students to pursue community-based research. An increase in the use of community-based research could provide unanticipated benefits to institutions and would be particularly beneficial to the communities who partner with academic institutions.

When considering the research that has been carried out in relation to community-based or participatory methods of research, there have been some important case studies that have been conducted that add insight into the process. In relation to participatory research, there have been case studies of the experience of individuals carrying out this kind of work (Kneifel, 2000; Maguire, 1993). The case studies conducted by Kneifel (2000) and Maguire (1993), both doctoral students, are process studies of carrying out participatory research; the studies explore what is learned from that experience. Other case studies have been conducted that focus on collaboration between universities and communities (Benson, Harkavy, & Puckett,1996; Reardon, 1995; Santelli, Singer, & DiVenere, 1998; Savan & Sider, 2003). These studies tend to emphasize the research that was conducted and carried out rather than the process of the collaboration. As has been mentioned, Reardon (1995) has provided a case study of a long-term participatory action research project between the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and East St. Louis; the case study explores different approaches to participatory research and what has been most effective in working with East St. Louis. Benson, Harkavy and Puckett (1996) have produced a case study describing a participatory action research project between the University of Pennsylvania and the community of West Philadelphia aimed at neighborhood and school revitalization, and there are many other case studies that seek to illuminate the field of community-based work (Chataway, 1997; Nyden et al., 1997; Wallerstein,1999)

Though there have been case studies exploring the process of implementing other kinds of participatory research (Kneifel, 2000; Maguire, 1993), there has not been an extensive study written about the researcher's perspective of the experience of participating in a long term community-based research project based on the new model of community-based research that has been provided by Strand et al. (2003a). The literature points to the need for additional case study work to inform the field of community-based research. Israel, Schulz, Parker, and Becker (1998) argue for "in-depth, multiple case study evaluations of the content and processes (as well as outcomes) of community-based research endeavours" (p. 194). Wallerstein (1999) says, "Although there has been an upsurge of interest in community-based research and its methodologic problems, there has been little written about the problematic relationships between communities and evaluators/researchers" (p. 40).

The purpose of the following contrasting case studies (presented in chapters four and five) is to explore the process of collaboration on community-based research projects through my partnership with a non-profit, educationally oriented organization in a western city and through my partnership with various members of the community in a small, western, mountain town who work with the immigrant population. My study adds to the field of community-based research methodology by exploring the process and outcomes of conducting community-based research.

The overarching question the study addresses is-what is the process of collaborating with a community partner on a community-based research project? Additionally, the study looks at four sub-questions:

What kinds of issues arise when collaborating on a community-based research project?

What facilitates or hinders the process of collaboration?

What does the researcher gain through this collaborative process, and what are the benefits for the community?

What can we learn from these experiences to inform the field of community-based research?

This study explores these questions by offering comparisons between two community-based research projects, one which was effective and one which was less effective. I label a project as an effective community-based research project based on four factors: the opportunity to work closely with the community dealing directly with the issues, the ability to develop an effective collaborative relationship with my community partners, the inclusion of the community in creating knowledge throughout the research process, and the creation of change or the potential for change. Through the comparison of these cases, this study provides insight into the difficulties and delights that come with using this research methodology.

This introductory chapter began with an exploration of the disconnect between academic researchers and the community and has introduced newly emerging methodologies to address this disconnect. The next chapter elaborates on the research traditions and philosophies that have joined to create community-based research. Chapter two also discusses the traditions of research and service within higher education and defines many of the constructs that are integral to understanding and carrying out CBR. Chapter three provides a description of the methodology chosen for this study, case study design, as well as providing details on the methodology of community-based research, the participants of the study, data collection and data analysis, and validity procedures. Chapters four, five and six present the findings of the study. Chapters four and five present the within-case descriptions and data analysis for each individual case, while chapter six presents the cross-case analysis and major findings of the study.

In order to understand the current model of community-based research that has been described by Strand, Marullo, Cutforth, Stoecker, and Donohue (2003a), it is important to place CBR within the context of the civic mission of higher education and to describe the various theoretical influences that have combined to create this new form of participatory research. This chapter provides an overview of the literature in relation to community-based research and also defines some of the important constructs that relate to this work, such as community and collaboration.

The Civic Mission of Higher Education

When considering the original mission of institutions of higher education in the United States, it is interesting to note how far we have strayed from historical intentions. According to Checkoway (2001), academic institutions were based upon the mission of developing citizenship and community involvement. Because of this mission, universities and colleges were connected to the real world beyond the institution in significant ways (Ward, 2003). The creation of land-grant institutions through the Morrill Act of 1862 created additional opportunities for those other than the wealthy to attend tertiary institutions (Maurrasse, 2001). Maurrasse (2001) and Cordes (1998a) have pointed to the original purposes of these land-grant institutions, one of which was to address community needs. Thus these institutions were inextricably linked to "public service or civic engagement" (Maurrasse, 2001, p. 17). Land-grant institutions provided a link between academic research and communities through the use of extension offices that translated research for the community so that it would be usable (Ward, 2003). Ward points out that the land-grant institutions solidified the idea of the three missions of the university: teaching, research, and service.

If civic engagement was one of the original intentions for institutions of higher education, what happened to create the separation from communities that typifies most institutions? According to Greenwood and Levin (2000), because of fears regarding the influence of religion and politics, institutions of higher education were designed to allow for intellectual autonomy. Since research agendas were determined within the institution, a sort of intellectual insularity began to develop (Greenwood & Levin, 2000). This insularity was deepened by the strictures of departmentalization in institutions (Benson, Harkavy, & Puckett, 1996) and the fact that dialogue tended to exist solely within academic disciplines (Greenwood & Levin, 2000). Academics end up simply talking to each other (Porpora, 1999), providing research that is reviewed and read by each other, and making the argument that "connections to the world beyond the university invade their intellectual autonomy" (Greenwood & Levin, 2000, p. 86). As stated frankly by Benson, Harkavy, and Puckett (1996), "In short, esoterica has triumphed over public philosophy; narrow scholasticism over humane scholarship" (Introduction section, para. 4). This intellectual fragmentation leads to barriers in developing knowledge and understanding that could lead to solutions for difficult social problems (Benson et al., 1996).

This disconnect between universities and communities is ironic if you consider the tripartite mission of research, teaching, and service that most universities espouse (Ansley & Gaventa, 1997; Boyer, 1990; Maurrasse, 2001). Benson et al. (1996) point out that intellectual fragmentation and the strictures of universities have separated these three missions, and they believe that this separation has impoverished all three missions. In looking particularly at the mission of service, Ward (2003) differentiates internal service (university committees and professional associations) and external service (consulting, service-learning, CBR). However, for most institutions service has come to mean professional service within departments or academic disciplines rather than service to the larger community (Checkoway, 1997). Checkoway (1997) argues that we need to redefine service as "work that develops knowledge for the welfare of society" (Introduction section, para. 4).

Though Checkoway (1997) proposes the idea of reconceptualizing service to include community-based work, Ansley and Gaventa (1997) believe that CBR should not just be categorized as service, as it is research. Ansley and Gaventa (1997) state,

Faculty members across the country who are engaging in these new forms of research too often report facing a double bind: their democratic research work may be tolerated and even rewarded, but only if they simultaneously demonstrate excellence and productivity in the traditional ways. Yet working with communities in a democratic and collaborative way takes time and makes demands at least as great as those that traditional researchers face (Reconstructing section, para. 5).

The concern is that if community-based research is only categorized as service, it will not gain status as an accepted research agenda.

Current university reward structures do not typically recognize community participation as important (Boyer, 1990; Reardon, 1995). Most academics gain tenure through a combination of publications, research, and teaching, with publications typically carrying greater weight (Benson et al., 1996; Boyer, 1990). As Ansley and Gaventa (1997) point out, "Scholars reap rewards not for contributions to community or civic life but for contributions to an expert knowledge base" (Introduction section, para. 3). With concerns over gaining tenure (Boyer, 1990), most professors are reluctant to venture in new directions.

As Lisman (1997) states, professors involved in community-based activities may be bypassed for tenure in favor of "professors [who] maintain their elite positions through conspiring with a research and publication reward system that produces countless articles and books of self-serving theory of limited use that often is only intelligible to scholars within one's own circle" (p. 84). Though there are new venues emerging in which to publish accounts of community-based or participatory research, there is still concern that this kind of work leads to limited publications (Reardon, 1995). This emphasis on publication has been partially responsible for the separation of the three missions espoused within higher education. Even after professors have gained tenure, once they have been acculturated into the academic environment and have developed a demanding traditional research agenda (Reardon, 1995), it can be difficult to break out of the mold.

There are important reasons, however, for universities to break the mold. There is growing concern in the United States about seemingly intractable social problems plaguing our cities (Chopyak & Levesque, 2002; Marlow & Nass-Fukai, 2000). Many universities, particularly those in urban areas, are surrounded by communities with significant and very real social problems (Benson et al., 1996; Greenwood & Levin, 2000; Maurrasse, 2001; Strand et al., 2003a). As stated by Benson et al. (1996), "For an urban university, it is difficult to be triumphant as its neighborhood collapses around it-untenable to be an island of affluence in a sea of raging and deepening despair" (Introduction section, para. 5). It is incongruous that many prestigious urban universities are surrounded not only by poverty and crime but also by walls (Maurrasse, 2001). Checkoway (1997) points out that some of the most esteemed research universities in America "have some of the greatest intellectual resources in the world, but they are not readily accessible to the community" (Introduction section, para. 3). If the intellectual capacity of these institutions were focused toward seeking solutions in the community around them, there would be the potential for significant change. Institutions of higher education have the choice to remain fortressed, insulated from these problems, or they can move out into the world and redefine the mission of service.

Some academics make the argument that universities do provide research for the community. Though it is true that academic institutions often conduct research in the community, it is typically research on the community, not for the community (Sclove, 1997). Many community organizations have negative perceptions of academic researchers because of the experiences they have had (Nyden, Figert, Shibley, & Burrows,1997). Most contact with researchers is usually through one of two venues: evaluation research, where organizations are judged and critiqued in ways that can impact their funding, or hit and run research where researchers venture into the community to collect data, then leave without sharing the results (Nyden et al., 1997). Because of these experiences, community members often "talk about feeling exploited by researchers" (Reback, Cohen, Freese, & Shoptaw, 2002, Historical Problems section, para. 1).

There are several reasons why many university academics have not become involved in participatory forms of research. Research agendas are typically determined by academics who are focused on adding to the knowledge base within their discipline (Siedman, 1998; Wallerstein, 1999), while other academics are concerned with maintaining scientific integrity (Greenwood & Levin, 2000). Research agendas are also influenced by sources of funding. Universities often receive funding from private corporations and the government. As Sclove (1997) points out, "Presently, across the world most research is conducted on behalf of private enterprise, the military, national governments, or in pursuit of the scientific community's intellectual interests" (p. 542). Not surprisingly, those that provide the funding influence the research (Ansley & Gaventa, 1997; Greenwood & Levin, 2000), and "very little research is conducted directly on behalf of citizens or communities" (Sclove, 1997, p. 542). Impoverished and disenfranchised communities typically have little influence (Greenwood & Levin, 2000) and, as a result, these communities have nowhere to turn for help in seeking ways to understand and alleviate social problems (Checkoway, 2001). As stated by Greenwood and Levin (2000), "The majority of people cannot look to universities for assistance with solutions to their most pressing problems" (p. 90).

The encouraging news is that many universities are now in the process of making renewed commitments to the communities around them (Checkoway, 2001; Maurrasse, 2001; Stoecker, 2001; Strand et al., 2003a). There are various reasons for this shift. Wallerstein (1999) points out that not only have communities pushed for greater participation, but also the government and private foundations, which underwrite many research initiatives, are pushing for greater community collaboration and participation. According to Cordes (1998a) "With universities under pressure to prove a public payoff for the vast sums of federal and state funds they spend, advocates say community-based research should be part of the answer" (A Minute section, para. 1). Chopyak and Levesque (2002) concur that institutions of higher education are "feeling pressure from financial backers to demonstrate how their universities are contributing to the communities in which they reside" (p. 204). Because of this pressure, many universities are seeking to integrate the three missions of research, teaching, and service (Maurrasse, 2001) in ways that are beneficial to both the institution and the surrounding communities, including instituting service-learning programs (Stanton, Giles, Cruz, 1999). Some are even taking things a step further by allowing the community to have input into the service or research provided (Maurrasse, 2001).

Many institutions are realizing that community involvement not only benefits the community, it also provides many benefits to the university. Communities receive educated manpower, resources, and expertise (Checkoway, 2001; Marlow & Nass-Fukai, 2000) while the university receives benefits as well through improvements in research. Researchers are provided with fresh perspectives which can dramatically improve the quality of their research (Checkoway, 2001). Researchers also have the opportunity to test research theories if carried out in community sensitive ways (Checkoway, 2001). Of course, for the students involved, community experiences can provide substantial gains in learning and growth (Benson et al., 1996; Checkoway, 2001). Universities are beginning to realize that community-based research, and others forms of community participation, has the potential to "unite all three academic missions-research, teaching, and service-in creative ways that enliven each other" (Cordes, 1998a, Balancing section, para. 4).

There are some difficulties that will need to be overcome in the process of renewing the civic mission of institutions of higher education. Many community organizations are distrustful of university researchers (Checkoway, 2001; Sclove, Scammell, Holland, 1998) because of past research situations where communities were studied and written about but left unchanged (Benson et al., 1996). As Maurrasse (2001) points out, "A lot of bitterness remains in local communities after decades of mistreatment from some universities or colleges" (p. 5). Academic institutions will have to prove themselves in order to develop effective working relationships with their communities. There are also existing structures within universities that inhibit community involvement that will have to be overcome (Checkoway, 2001), such as departmentalization (Maurrasse, 2001). New interdisciplinary structures will have to be created to allow collaboration across departments and disciplines (Greenwood & Levin, 2000). Though changes will have to be made in order to facilitate greater community involvement, the resulting benefits will make the effort worthwhile.

Though community-based research has been described by some as a new research movement (Cordes, 1998a), Stoecker (2001) has pointed out that it is not a new movement per se but rather a confluence of other existing participatory research models that have developed both inside and outside academia (Stoecker, 2002b). As a result, there is a confusing mix of nomenclature used to describe this kind of research: participatory research, action research, participatory action research, collaborative action research, community based inquiry, and the list goes on (Ansley & Gaventa, 1997; Creswell, 2002). A common theme to these various forms of research is that they "emerged as resistance to conventional research practices" (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2001, p. 572), and most of them include a collaborative component between the researcher and the community or organization participating in the research (Fals-Borda & Rahman, 1991; Greenwood & Levin, 1998; Kemmis & McTaggart, 2001; Stringer, 1999; Whyte, 1991).

Strand (2000) describes two alternatives to the positivist research paradigm: interpretive research and critical research. Community-based research is located within the paradigm of critical research. Critical research, which has its roots in Marxism, focuses on issues of power and inequality. According to Strand (2000),

Critical researchers are less concerned with questions of how to do social research than with questions of why to do it and who is entitled to shape and control the research process. The purpose of all social inquiry, they argue, should not simply be to describe the world, but to change it (p. 92).

Therefore, CBR differs from traditional academic research in two ways. First of all, CBR is conducted "with rather than on the community" (Strand, 2000, p. 85). Though it does not always happen, the goal is to involve community members in every stage of the research process. The research problem is defined by the community and not by the researcher. It is a democratic process that values the knowledge of powerless people. The second primary difference between CBR and traditional academic research relates to purposes. The primary purpose of CBR is to create change; the focus is on social change (Strand, 2000).

The two research models that have had the greatest influence on the development of community-based research are action research and participatory research (Stoecker, 2001; Strand et al., 2003a). Action research, also called industrial action research (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2000), came about through the work of Kurt Lewin, a social psychologist who did pioneering work in the field of industry during the 1940s (Ansley & Gaventa, 1997; Greenwood & Levin, 1998; Reason & Bradbury, 2001). Action research was originally developed as a methodology to deal with social concerns (Creswell, 2002). Greenwood and Levin (1998) define action research as "social research carried out by a team encompassing a professional action researcher and members of an organization or community seeking to improve their situation" (p. 4).

Stoecker (2001), though recognizing the pioneering efforts of action research in the field of participatory methods, criticizes the fact that the movement did not challenge existing power structures. As stated by Stoecker (2003), "Action research values useful knowledge, developmental change, the centrality of individuals, and consensus social theories...Action research does not address power differences but seeks to resolve conflicts between groups" (p. 37). Stoecker (2003) points out that action research is based on the sociological theory called functionalist theory which argues that "society tends toward natural equilibrium and its division of labor develops through an almost natural matching of individual talents and societal needs" (p. 40). People end up in whatever role they are supposed to be in-thus the poor are playing their role of being poor. Functionalist theory views the idea of rapid change as unhealthy in that it upsets balance and instead promotes the idea of steady change through cooperation (Stoecker, 2003). Stringer's (1996) description of action research concurs with Stoecker's (2001) argument. Stringer (1996) says,

[Action research] is fundamentally a consensual approach to inquiry and works from the assumption that cooperation and consensus making should be the primary orientation of research activity. It seeks to link groups that are potentially in conflict so that they may attain viable, sustainable, and effective solutions to their common problems through dialogue and negotiation (p. 19).

However, Stringer's consensual approach to action research is not mirrored by all of those who work in the field of action research. Greenwood and Levin (1998), for example, do not promote a consensual approach to action research.

Though the term action research has traditionally been associated with industrial settings, action research took on a different form in the 1970s as a method that was modified by teachers to improve their teaching practices (Creswell, 2002). This form of action research is also called practical action research (Creswell, 2002) or classroom action research (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2000). With practical action research, teachers research their own teaching practices to determine improvements that could be made (Creswell, 2002). This research may be done by individual teachers working alone or with the collaboration of research experts (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2000).

The second research model that has had a direct impact on the development of community-based research is participatory research. Participatory research developed as a research movement in third world countries during the 1960s and has its roots "in liberation theology and neo-Marxist approaches to community development" (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2000, p. 568). "In Latin America, Paulo Freire and Orlando Fals-Borda and other activist educators and researchers used what they called 'participatory research' as an organizing and transformative strategy for the disenfranchised" (Strand, 2000, p. 86). The original purpose behind the movement was to give third world farmers leverage in resisting exploitation from large agricultural corporations (Stoecker, 2001). It also appeared in Europe and North America in the 1960s and 1970s "during an era of challenge to the dominant positivist paradigm" (Strand, 2000, p. 86).

The basic attributes of participatory research are "shared ownership of research projects, community-based analysis of social problems, and an orientation toward community action" (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2000, p. 568).

The work of Paulo Freire has had an important influence on the field of participatory research (Stoecker, 2001). Freire's (1970) ideas about shared control and shared creation of knowledge as the means of empowerment have played an important role in developing the ideology of participatory research and other forms of alternative research (Greenwood & Levin, 1998). Participatory research was promoted in the U.S. through the Highlander Research and Education Center (Stoecker, 2003). The founder of Highlander, Myles Horton, a subsequent director, John Gaventa, and Paulo Freire provide the philosophical foundation of what is called the population education model. Stoecker (2002a) defines popular education as "a participatory approach to learning that makes participatory research a central part of the learning process. Research is not done just to generate facts, but to develop understanding of one's self and one's context" (p. 9). Unlike action research, participatory research does not shy from conflict. In fact, participatory research "emphasizes the centrality of social conflict and collective action, and the necessity of changing social structures" (Stoecker, 2003, p. 37). Stoecker (2003) states that participatory research is based on conflict theory. Conflict theory purports that society is in constant conflict over limited resources, and stability only happens rarely when "one group dominates the other groups" (p. 41).

The terms participatory research and participatory action research are used by some researchers interchangeably (Fals-Borda, 2001; Greenwood & Levin, 1998). Kemmis and McTaggart (2000), however, see participatory action research as the overlap between action research and participatory research. According to Wallerstein (1999), "While both action- and participatory-research traditions remain partially separate in their goals and change theory, they share enough commonality so that some researchers have begun to use the term participatory action research" (p. 41). According to Soltis-Jarrett (1997), however, there are both philosophical and methodological differences between participatory action research and social action research. Soltis-Jarrett states,

Simply put, social action research is a study designed by a researcher who is interested in the identification and solving of problems in a specific group of individuals. Change is usually the intended outcome of the study. Participatory action research, on the other hand, is a study designed by a group of participants (researcher-facilitator included) that focuses on the identification of concerns that become apparent through the critical process of observation, reflection, and transformation. It is through this process that the group can then collectively seek to uncover the possibilities for their actions so that they may be freed to implement changes in their lives (Introduction section, para. 3).

According to Soltis-Jarrett, though both research models are intended to create change, participatory research focuses on empowerment as part of this change process.

However, there is a strand of action research, called emancipatory action research, that does focus on empowerment as part of the research process. Carr and Kemmis (1986) are advocates for this version of action research. Though the goal of emancipatory action research is to create change, it also focuses on the learning that groups of research participants obtain through the collaborative process of exploring issues. Carr and Kemmis believe that it is through this critical process that the research participants recognize their ability to become agents of change and are thus empowered.

Another important influence on community-based research is the service-learning movement in higher education. Stoecker (2001) points out that much of the current involvement in community-based research stems from involvement with the service-learning movement. Though service-learning has the potential to provide interesting opportunities for students, it does not necessarily encompass an agenda of change for the community (Stoecker, 2001; Strand et al., 2003a). Though students may grow through the process of providing service to community partners, there is some concern about the lasting impact of the service on community organizations (Maybach, 1996).

As mentioned in chapter one, there are two models of service-learning that have surfaced, charity service-learning and social justice service-learning (Marullo & Edwards, 2000). Charity service-learning is linked to the philosophy of Dewey (Stoecker, 2003). Stoecker describes Dewey's "approach to change as one of mediation and gradual reform" (p. 38). Therefore, traditional service-learning (charity service-learning) is more compatible with action research as it does not challenge power structures (Stoecker, 2002a). Social justice service-learning focuses on creating social change and is linked closely to the popular education model of Freire. The goal is to use education as resistance against power structures that maintain domination of the elite. Thus social justice service-learning is more closely aligned with participatory research methods (Stoecker, 2003). In determining which type of service-learning approach individual institutions will pursue, it will be important to consider not only student learning, but also the needs of the community (Strand, 2000). As Strand (2000) says, "we should do more to ensure that our students' service-learning efforts are truly beneficial to the communities where they work" (p. 95)

Some academics who recognize the benefits of service-learning, but would like to create a more extensive impact, are turning to community-based research as a vehicle for change (Stoecker, 2001). In fact, Porpora (1999) has argued that community-based action research might be considered "a higher stage of service-learning" (p. 121) in that it combines service, teaching, and research.

Willis, Peresie, Waldref, & Stockmann (2003) describe CBR as "an intensive form of service learning" (p. 36). As Strand (2000) points out, researchers and community activists have been participating for decades in a range of action and participatory research methods. However, it is only recently that community-based research has been described as a form of service-learning.

Though community-based research has it roots in other methods of participatory research, the form of community-based research utilized in this study is more directly linked to universities (Strand et al., 2003a). As stated by Stoecker (2001), the current community-based research movement is a "uniquely academic version of community-based research" (p. 3). This movement has come about partly because of the recognition from members of academic institutions as to the importance of the university's role in assisting communities but also because of public demands for universities to provide a return for the investment of federal and state funds (Cordes, 1998a). Whatever the impetus, this new research movement has the potential to connect academic institutions to communities in many beneficial ways.

Stoecker (2003) has recently delineated two streams of community-based research, radical CBR and mainstream CBR. Mainstream CBR combines the philosophy of Dewey, the traditional charity service-learning approach, action research methodology, and functionalist sociological theory. Stoecker states,

[Mainstream CBR] sees reform as a gradual, peaceful, linear process...[and] attempts to mediate divisions across social structural boundaries, implicitly reflecting that common interests between the rich and the poor, for example, are more powerful than their differences. All follow an expert model, either through choosing agencies rather than grassroots groups as partners, or through professional control over both the research and teaching processes (p.39).

Alternately, radical CBR combines the popular education model of Freire, the social justice service-learning model, participatory research methodology, and conflict sociological theory (Stocker, 2002a; Stoecker, 2003). According to Stoecker (2002a), "popular education and participatory research, because of their mutual emphasis on structural change, collective action, and a conflict worldview, are beginning to form a radical version of CBR" (p. 9). Within this radical model of CBR, research partnerships are usually developed with grassroots organizations versus social service agencies. Table 1 provides a comparison of these two models of CBR.

| Educational Philosophy | Sociological Theory | Community Partners | Model of Service-Learning | Research Base | |

| Mainstream CBR | Dewey | Functionalist | Social Service Agencies | Charity SL | Action Research |

| Radical CBR | Freire | Conflict | Grassroots Organizations | Social Justice SL | Participatory Research |

Stoecker (2002a) expresses the concern that it is more likely that proponents of CBR will adopt the mainstream approach versus the radical approach. If so, "The question arises whether our distaste for conflict situations, and conflict groups, and our gravitation toward safe 'middle' service organizations may be making it difficult to achieve the third principle of CBR, which is social change for social justice" (p. 9)

The danger in moving closer to the mainstream version of CBR is that at some point, the research is no longer community-based research; it becomes simply consulting based on the traditional expert model or possibly a collaborative form of consulting. What is the difference between consulting and CBR? What Whyte (1991) calls the professional expert model is in reality consulting. Whyte (1991) states, with the professional expert model:

The professional researcher is called in by a client organization-or talks his or her way in-to study a situation and a set of problems, to determine what the facts are, and to recommend a course of action...the professional researcher is completely in control of the research process except to the extent that the client organization limits some of the research options (pp. 8-9).

The consultant views him or herself as the expert who explores problems or conducts evaluations and recommends solutions or new avenues. Bentley (1998) describes this role as the "non-involved and confidential advisor" (Introduction section, para. 1).

Consultants are hired for various reasons, usually to "fix" issues. "In this role consultants are expected to diagnose what is wrong and to put forward the appropriate prescription for a cure" (Bentley, 1998, Providing section, para. 1). Though the consulting process may follow many of the same research stages of CBR-defining the problem, developing a research question, collecting data, analyzing data and communicating the results (Nyquist and Wulff, 2001), the difference is the client's (community's) input in the process. The consultant is not really concerned with collaborating with the client on all stages of the research process. The consultant is viewed as the expert uncovering issues and often providing training to address issues revealed in the research process (Dallimore & Souza, 2003). Organizations usually use information or products developed by the consultant to inform decision making or make new policy (Seargeant & Steele, 1998). Stoecker (1999) points out that in many situations where academic researchers are attempting to create a participatory research process, they in fact "find themselves consulting with community groups" (p. 844). In this scenario, the researcher carries out research but is accountable to the community (Stoecker, 1999). Though this form of consulting may be more collaborative than traditional consulting, it is not truly CBR.

Strand et al. (2003a) describe community-based research as the "next important stage of service-learning and engaged scholarship" (p. xxi), but what exactly is CBR? Stated simply by Sclove et al. (1998), "Community-based research is research that is conducted by, with, or for communities" (p. ii). It is a collaborative form of inquiry between academic institutions and community members (Strand et al., 2003a) that seeks to offset the prevalence of traditional academic research by acknowledging the expertise that community members contribute to the research equation (Hills & Mullett, 2000). Community organizations or members are involved with the research process from the beginning, helping to determine the direction of the research, providing community knowledge, and assisting in the research process (Hills & Mullett, 2000). This process is conducted with the goal of solving problems or creating change (Hills & Mullett, 2000; Strand et al., 2003a) that leads to social justice. Stoecker (2003) says, "In the most concrete sense, CBR involves students and faculty working with a community organization on a research project serving the organization's goals" (p. 35).

Though qualitative research methods are more closely aligned with this kind of process, quantitative methods may be used as well (Strand, 2000). As Hills and Mullett (2000) point out, CBR "is more concerned with methodology than it is with method" (p. 1). Strand (2000) mentions that regardless of the fact that students may use quantitative methodology (usually surveys), the content of the instrument is developed through a collaborative process with members of the community "who have a stake in the information they yield" (p. 90). And, "they are compiling, interpreting, and presenting data imbued with meaning far beyond mere numbers and with potential to bring about needed social changes consistent with the students' own values" (p. 90). Strand also makes the point that combining quantitative data with qualitative data can sometimes be more persuasive for community organizations who are seeking funding or support for their position. The researcher assists in designing a study that will provide the most benefit to the community in contributing the information they will need to assess options or access resources (Greenwood & Levin, 2000).

Community-based research is opposed to the idea of forcing research on people (Greenwood & Levin, 1998); instead it seeks to empower community members through valuing their knowledge (Hills & Mullett, 2000; Strand et al., 2003a) and helping them find solutions that work for them (Stringer, 1999). As Sclove et al. (1998) point out, "community-based research is intended to empower communities and to give everyday people influence over the direction of research and enable them to be a part of decision making processes affecting them" (p. 1); empowerment is an important aspect of this process. Though community members may gain research skills through this collaborative process (Hills & Mullett, 2000), it is a sense of empowerment that creates the realization of the possibility for change. In defining empowerment, Perkins and Zimmerman (1995) state,

[Empowerment is] an intentional ongoing process centered in the local community, involving mutual respect, critical reflection, caring, and group participation, through which people lacking an equal share of valued resources gain greater access to and control over these resources (p. 570).

It is through the combination of assisting the community in seeking information and allowing for the possibility of empowerment that creates the potential for sustainable change in the community.

Though constructing a definition for community can be difficult, when considering community-based research, it is important to define or determine what is meant by community. Checkoway (1997) defines community as "people acting collaboratively with others who share some common concerns, whether on the basis of a place where they live, of interests or interest groups that are similar, or of relationships that have some cohesion or continuity" (Community Needs section, para. 5). Though Checkoway uses the terms common and cohesion, it is also important to realize that communities consist of multiple voices (Wallerstein, 1999). So who is the community in community-based research? Stoecker (2001) points to grassroots community members and community organizations, though research tends to be carried out with organizations. These organizations may include "social service organizations, community development corporations, and government agencies" (Stoecker, 2001, p. 15). Strand et al. (2003a) also include educational institutions. Though community can mean any number of various groups or organizations, the communities targeted for community-based research are essentially any group of people who are subjugated and powerless (Strand et al., 2003a).

Stoecker (2002b) expresses concern that researchers carrying out CBR projects do not always end up truly working with the community. Ideally CBR projects would be carried out with grassroots organizations (Stocker, 2002b); however, the reality is that many CBR projects are carried out with what Stoecker calls "mid-range organizations" (p. 232). The concern is that some of these organizations may be too far removed from the communities they purport to represent and therefore do not truly act in the community's best interests (Stoecker, 2002b). Since the purpose of CBR is empowerment as well as social change, involving those people who are dealing with the issues directly provides greater potential to create effective change (Stocker, 2003).

Though community-based research has the potential to provide useful benefits to community members, there has been criticism directed at this kind of research. The typical concerns that some academics have about qualitative research in general are intensified in relation to community-based research. Cordes (1998a) and Stringer (1999) point out that some critics decry that it is not genuine research because it is not scientific, and Creswell (2002) points to the critique that the research is too changeable. Others express concerns about validity. Greenwood and Levin (2000) prefer the terminology of credibility versus validity. When addressing concerns about internal credibility, Greenwood and Levin (1998) feel that the research results are credible if they are credible to the group that creates or evaluates them. The true test of credibility is whether the research is successful in bringing about substantive change that benefits the community (Greenwood & Levin, 2000). When considering external credibility, Greenwood and Levin (1998) purport that "only knowledge generated and tested in practice is credible" (p. 81) and therefore generalizable. Though research resulting from this kind of work is very contextual (Greenwood & Levin, 2000) that is not to say that the knowledge gained through this kind of research cannot be what Eisner (1998) describes as transferable to other situations.

Other concerns about participatory methods of research relate to concerns about influences on the research. Some critics point to the possibility that if the researcher becomes too involved with the lives of the participants the research results may be impacted by these relationships (Cordes, 1998a). Stoecker (2002a) argues that researchers who do not have a relationship with the community do not get good results because community members will not be open and truthful because of a lack of trust. It is through developing a relationship that the researcher is able to gain more accurate results. Cordes (1998a) also points out that if researchers come to care about the people they are working with, they will be more focused on making sure that they are producing credible research results. And, as Strand (2000) says, "community members expect research that is rigorous and of high quality...communities want results, after all, that are credible and persuasive" (p. 94). Another concern that has been expressed by some researchers is the potential for a small, but vocal, minority to set itself up to speak for the whole group (Cordes, 1998a). This concern can be sidestepped fairly easily if the researcher takes the time to get to know the community and seeks multiple sources of knowledge within that community rather than aligning him or herself with one faction of the community.

Along with criticism relating to credibility, there are also concerns about the process of doing this kind of research and the difficulties it can create for faculty and students. Time is often a primary concern. Engaging in collaborative research can be a time intensive endeavor for faculty, students, and community members (Ansley & Gaventa, 1997; Sclove et al., 1998; Stoecker, 2001). Just the process of negotiating the research question alone can take a significant amount of work. Time is particularly an issue when professors try to include community-based research as a component of a course, as the timetables of semesters and quarters are not typically conducive to the completion of these kinds of projects (McNicoll, 1999; Sclove et al., 1998). Other concerns relate to writing up the data. Attempting to write up research results from this kind of work into a publishable article can be difficult (Cordes, 1998a), and professors concerned about gaining tenure may feel it is too risky (Sclove et al., 1998). There is also the issue of who owns the data. Cordes (1998b) says that both the researcher and the community own the data. However, Stoecker (2001) states that "an increasing number of community organizations make academics sign agreements to not write about the research without community permission" (p. 9). Since this may limit the possibility of publishing an article around the work, this places another obstacle in the path of pursuing publications for tenure.

Despite concerns relating to community-based research, there are many benefits for academic institutions and students as well as community members. One potential benefit for universities is that this kind of research creates the possibility for collaboration across disciplines (Greenwood & Levin, 1998). Since community-based research is not specific to one academic discipline, there is the potential for greater cooperation across departments and between colleges (Greenwood & Levin, 2000; Reardon, 1995). When divisions within a university work together for the betterment of the university and for students, positive results tend to occur. Not only will students benefit from a more cohesive institution, they also have the opportunity to be involved in hands-on learning experiences (Stoecker, 2001; Strand, 2000) that can be very meaningful (Cordes, 1998a). Students also gain valuable research skills from participating in community-based research projects (Benson et al., 1996; Reardon, 1995; Strand, 2000).

Faculty who have designed courses around community-based research projects believe that CBR greatly enriches the skills that students develop in relation to research as well as other areas (Strand, 2000). Willis, Peresie, Waldref, and Stockmann (2003), students who participated in community-based research projects at Georgetown University, outline four areas in which they believe CBR positively impacts students. These include: "enrichment of traditional academic coursework, increased sense of empowerment, greater understanding of social problems, and integration of academics and service" (p. 40). Strand (2000) also points to the relational skills that students develop such as tact, perseverance, and tolerance for ambiguity. These skills that students develop are desirable to employers who prefer to hire "graduates with 'real-world' experience behind their degrees" (Chopyak & Levesque, 2002, p. 204). However, CBR experiences are not only important to students because of the skills they develop, they are also important in that they are typically meaningful, and they provide a sense of purpose to schooling (Strand, 2000). Also, the fact that students are working and providing research for real people pushes them to produce top quality work, which makes the learning process more fulfilling (Strand, 2000).

Finally, the community itself benefits through this kind of research, primarily because the community is provided with research results that are both applicable and useful (Sclove et al., 1998). According to Ansley and Gaventa (1997), both the university and the community gain social capital. Through CBR work, each develops a network of resources and knowledge that provides advantages for both. It is also important that those who are dealing with the problem are allowed to help seek solutions to these problems. As stated by a community member who participated in a community-based research project, "We have to involve the people whose lives are involved" (Cordes, 1998a, Conclusion section, para. 5).

Since collaboration is such an essential component of community-based research, it is important to explore the construct of collaboration. I will begin with providing a definition for collaboration. According to Seaburn, Lorenz, Gunn, Gawinski, and Mauksch (1996),

To collaborate is to create conversations in which people are joined together, meanings are fashioned, purposes are defined, roles are clarified, goals are established, and action is taken. Together the participants create a...culture in which the whole is greater than the sum of parts (p. 9).

A simpler definition is that it is a shared decision making process (Marlow & Nass-Fukai, 2000). Traditionally, the process of collaboration has been described as a linear process (Bradley, 1999). However, those who practice and write about collaboration, whether in the field of education or in other fields, are questioning this linear model. Some are pointing to chaos theory as a model for representing the complexity of the collaborative process (Bradley, 1999; Goff, 1998), as collaboration is often difficult and chaotic (Christenson, Eldredge, & Ibom, 1996; Marlow & Nass-Fukai, 2000; Solomon et al., 2001).

The reason that collaboration can be difficult is because it deals with relationships between individuals (Christenson et al., 1996). Developing and maintaining these relationships is typically an ongoing and multi-layered process (Solomon et al., 2001). Though this process is not always linear, there are phases or stages that typify collaborative endeavors. According to Seaburn et al. (1996), the process begins with an "initial period of self disclosure, checking each other out, and building trust" (p. 47). As the relationship develops and confidence increases, the collaborators begin to consider each other and grow together. Carter (1998) describes the collaborative process in less relational terms. Carter delineates the phases of collaboration as problem setting, direction setting, and implementation. Whatever the process, the reality is that collaborations are founded on relationships (Christenson et al., 1996; Seaburn et al., 1996).

The first step in developing collaborative relationships is to identify the stakeholders who are in play (Bradley, 1999). According to Goff (1998),

Identifying stakeholders begins with an analysis of the perspectives necessary for defining problems and solutions, not with the names of powerful individuals of organizations that need to be represented. The perspectives of those affected by problems or solutions and those who may be part of the cause of problems are especially important. Everyone involved in the problem needs to be involved in the solution (Development section, para. 9).

It is also important to realize there are often differing agendas among the stakeholders (Solomon et al., 2001; Verbeke & Richards, 2001), as well as differing agendas between stakeholders and researchers (Wallerstein, 1999). An important part of the interpersonal work at the beginning of the process is to negotiate these differences (Solomon et al., 2001), as the process is most effective when all of the collaborators have a stake in the project through common goals (Seaburn et al., 1996; Solomon et al., 2001; Verbeke & Richards, 2001). Dialogue is imperative in this process of negotiation and goal identification (Marlow & Nass-Fukai, 2000; Seaburn et al., 1996). The willingness to communicate is a sign of mutual respect (Seaburn et al., 1996) among the parties involved and assists in the process of identifying strengths. When identifying strengths it is important to realize that "[a]ll of the participants play vital roles. Each brings experiences, knowledge, skills, beliefs, and wisdom to bear on the task of resolving problems, stimulating change, and alleviating suffering" (Seaburn et al., 1996, p. 9).