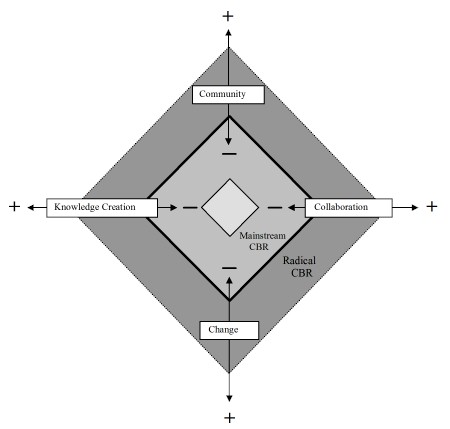

| Figure 2 Continuum of CBR |

||

| Consulting | Mainstream CBR | Radical CBR |

|

|

||

| Tinkler: Establishing a Conceptual Model | COMM-ORG Papers 2004 | http://comm-org.wisc.edu/papers.htm |

|

Contents | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Notes & References | Appendices | ||

If you are here to help me, then you are wasting your time. But if you come because your liberation is bound up in mine, then let us begin (McNicoll, 1999, New Perspective section, para. 5).

According to Creswell (1998), when using a multiple case study design, the usual formula is to "first provide a detailed description of each case and themes within the case, called a within-case analysis, followed by a thematic analysis across the cases, called a cross-case analysis, as well as assertions or an interpretation of the meaning of the case (p. 63). The two previous chapters provided a description of the process of collaborating on community-based research projects in two different settings, addressing the primary question of the study: What is the process of collaborating with a community partner on a community-based research project? Though there were some similarities in these cases, there are considerable differences as well. This chapter provides a cross-case analysis of these two contrasting cases by highlighting the differences between the two cases and comparing data from each case to answer the sub-questions of the study: what are the issues that arise when collaborating on a CBR project, what facilitates or hinders the process of collaboration, and what are the benefits for the researcher and the community. In considering the implications of this study for the field of community-based research, this chapter introduces a conceptual model that was developed based on the insights provided through these experiences. This addresses the final research question of the study: What can we learn from these experiences to inform the field of CBR?

When comparing the two cases, it is interesting to note the differences between the two experiences. From my perspective as the researcher in this process, my collaboration with the Coalition of Schools was not always successful, and in many ways I would not consider this process to be community-based research, rather, as Maguire (2000) would describe it, it was an attempt at community-based research. However, the research that I carried out with John Brewer and Maria Swenson, in relation to the immigrant population in my small town, was a successful collaborative process, and I believe this process was community-based research. In comparing and contrasting these two cases, I return to the four constructs of my analytic framework: community, collaboration, knowledge creation, and change. Considering these four constructs based on the continuums presented in figure 1 (p. 63), you can compare the facets of these two case studies. Table 2 provides this comparison.

Table 2 - Contrasting Cases of CBR

| Community | Collaboration | Knowledge Creation | Change | |

| Coalition for Schools | Mid-Level Organization | Limited Collaboration | Limited Participation | Minimal Programmatic Change |

| ESL Program | Bridge People Working Closely with the Community | Shared Decision Making | Partial Participation | Potential for Substantial Programmatic Change and Structural Change |

In considering how to define community, I work from Stoecker's (2002a) definition that the community is the people who are dealing directly with the problem. Based on this definition, I did not work directly with the community on either of the CBR projects that I completed. However, the two cases present differences in how closely my collaborators worked with the community and how committed they were to seeking community input. My work with the Coalition for Schools was what Strand, Marullo, Cutforth, Stoecker, and Donohue (2003a) would describe as "doing CBR in the middle" (p. 73). The Coalition was a midlevel organization that did have some community grounding, but the organization presented conflicting messages about how much it sought and valued community input. Though they did invite grassroots community organizations to become members of the Coalition, and they did direct some grant funding toward community collaboration, they did not actively seek community input in relation to certain strategic decisions about data, and they did not seek to communicate with all members of the community. Also, during my work with the Coalition, I had fairly limited access to the community.

In working with John Brewer and Maria Swenson, I felt a direct connection to the community. Though John and Maria are not actually the community themselves, as they are not dealing directly with the problems that the immigrant population deals with, they work closely with the community, and they are well aware of the issues that the immigrant community faces on a daily basis. John and Maria are what Stoecker (2002a) describes as bridge people in that they provide a link to the immigrant population and the broader community around them. John and Maria also actively seek community input in their work, and they both realized and supported the idea that community input was integral to our research together; we included community input on the structure and content of surveys, we sought community input through the data collected from the surveys, and we began the process of organizing the community so that the immigrant community can have greater input in city affairs.

I conceptualize the construct of collaboration as shared decision making (Strand et al., 2003a). The potential to develop a shared decision making process relies on the possibility of developing a relationship (Stoecker, 2002a), and relationships can be impacted by communication, trust, and issues of power. In my work with the Coalition, our initial relationship did encompass some shared decision making. However, this initial collaboration became a situation where decisions were made primarily by Lisa Brown and Marge Bowline. After repositioning my role in my work with the Coalition, I made most of the decisions with only limited input from Lisa and Marge.

Part of the reason that our collaboration was not successful was that we were not able to develop a productive relationship. One of the primary factors that limited the development of a relationship related to issues of power. Since we did not clearly define my roles and responsibilities at the outset, Lisa and Marge viewed me as an employee. I also felt that Lisa was coerced into working with me, and so she also lacked power in this situation. Another factor that limited our potential to cultivate a relationship was the fact that we did not trust each other. Lisa did not trust my work ethic and capabilities, and I did not trust her organizational skills. If we had been able to communicate effectively, it may have alleviated some of these issues; however, an over-reliance on email probably complicated things further. Finally, our relationship was hindered by what I felt to be a lack of consideration for my other obligations and my dissertation research.

My collaboration with John Brewer and Maria Swenson was successful in that decision making was shared throughout our work together. There were no dynamics around power in the collaboration because all of us agreed to work together and no one felt coerced. Also, I made sure that my roles and responsibilities were clear from the outset, and that both John and Maria had a full understanding of the work to which they were committing. Because of the fact that we chose to work together, we were able to develop a productive relationship. This relationship was based on communication, trust, and consideration for each other's needs.

Part of the reason that communication was effective was that I took the time to get to know John and Maria and to understand how they communicated. We primarily met face-to-face and this facilitated more extensive dialogue. Though communication was effective, it was not always perfect. There were times that I felt that John contradicted himself, and there were gaps in communication in keeping me apprised of issues relating to our research and gaps in communication between John and Maria. However, since we had developed a trusting relationship, these issues did not hinder our work together. This trust was based partly in the fact that we had similar life experiences and similar views of the world. And this trust allowed us to work past differences of opinion, particularly in relation to my disagreement with John about the approach to community organizing. Finally, our relationship was strengthened by the fact that we all demonstrated consideration for each other in relation to timelines and other obligations.

One of the goals of community-based research is that the community should participate in all stages of the research process (Strand et al., 2003a). There is a reciprocal process of knowledge sharing between the researcher and the community. Since the knowledge of the community is valued, and the community gains additional knowledge through the research process, this experience can be empowering for the community. This potential for empowerment is an interesting outcome that may be an aspect of the change that can occur through the CBR process.

In my work with the Coalition, the creation of knowledge was not a shared process. The only participation from Lisa Brown and Marge Bowline in the process was to determine what data to collect. Later, after I moved to a consulting position, they did not even have this input. One of the factors that prohibited their participation was the fact that we did not start off our work together by defining goals; instead, I began data collection without a plan. Though both Dr. Green and I pushed for dialogue to define goals, Marge and Lisa did not recognize that this was important. Another factor that limited participation was the fact that we had differing views about the use of data. Though I understood Marge's desire to use data as a means to provoke action, I wanted to pursue a research agenda that encompassed using data in a variety of ways.

Though I did try to work toward a plan for data collection, it was difficult to make progress since I felt that my knowledge was not valued. The work that I carried out was constantly critiqued in a way that was discouraging rather than constructive. Not only did I feel like my work was not valued, I was also held to deadlines that were unrealistic either because of unavailable data or because of lack of timeliness in a response from Marge and Lisa. Finally, Marge and Lisa often held unrealistic expectations of what I would be able to accomplish working part-time. Because of their lack of understanding and knowledge of research, they did not realize the time intensive nature of collecting and analyzing data.

Working with John Brewer and Maria Swenson was a very different experience. John participated in all stages of the research process, and Maria was very active as well. Though John did not participate as extensively with data analysis and with writing the report, he still had input in those stages as well. We also sought input from the community in developing various instruments, and community members helped administer the survey. However, the community was not involved in the other stages of the research process. Though I view it as a success that John and Maria were active participants, it would have been even more successful if we had worked closely with community members to help determine the research focus and in the data analysis and reporting stage.

Part of the reason that John was willing to participate throughout was that we worked together to develop goals to pursue based on John's needs and interests. As I worked with John and Maria, we added additional goals that all related to better serving the needs of the immigrant population. The reason that we were successful in collaborating to develop these goals was that we held similar views about the use of data. John viewed data as a way to obtain feedback that would help improve his program, and Maria viewed data as a way to get information in order to make educated decisions. Also, they both had experience with research so they had reasonable expectations for the work that we would carry out.

Based on John and Maria's experience with research, they also had expectations for the quality of the data that we pursued which helped add rigor to the data collection process. As I worked with them, I valued their knowledge of research as well as their knowledge of the community they serve. They also valued my knowledge and expressed appreciation for my work. Because of the fact that I valued their input, I was open to constructive criticism and did not view their criticism as an expression of doubt in relation to my abilities.

Though John and Maria were both timely in working toward the completion of projects, the process of collaboration takes time. Since John had a busy schedule, it was usually up to me to keep the process moving. Regardless of the fact that I did try to keep things moving in relation to the completion of all areas of research, I was unsuccessful in completing a demographic estimate of the immigrant population in town. Though John did not express concern over this, I did feel as if I had not fulfilled all of the expectations for our research.

The ultimate goal of community-based research is social change that leads to social justice (Strand et al., 2003a). In my work with the Coalition, there was only very little change that occurred through my work with them. I did create greater awareness of the work of the Coalition for some teachers and parents that I came into contact with through interviews; however, this was a fairly limited group of people. Lisa stated that some of the work that I completed has provided a foundation for continued work, including the statistical data I collected and the review of literature. However, it seems likely that my work only led to minor programmatic change, if at all.

My work with John Brewer and Maria Swenson was much more successful and has the potential to create greater change. John and Maria both gained research skills through the development of the surveys, and the surveys that we developed will likely lead to programmatic change. This programmatic change will potentially make the English program more accessible for all immigrants as well as prompt revisions to classes so that they better meet the needs of the students currently attending the program. In addition to programmatic change, the groundwork that we laid in initiating the process of community organizing has the potential to even lead to structural change within the community in that the immigrant community may at some point have greater power within the community.

When considering the continuum of CBR in Figure 2, it is interesting to contemplate where each of these cases falls on the continuum.

Based on the four constructs, my work with the Coalition could be characterized initially as mainstream CBR, but when my role was repositioned to allow me to have greater input in decisions about data, the process moved toward consulting. My work with John Brewer and Maria Swenson would be characterized as mainstream CBR, however, we moved toward radical CBR by initiating the process of community organizing.

The within-case descriptions and analysis addressed the overarching research question: What is the process of collaborating with a community partner on a CBR project? The cross-case analysis addresses the sub-questions of the study. Most of the findings presented in this section are themes that emerged in both cases.

The first sub-question of this study is-What kinds of issues arise when collaborating on a community-based research project? I define an issue as a matter of concern that could typically arise in any CBR project. An issue does not have to be a factor that interferes with creating a successful collaboration, but it is something that the researcher needs to consider when carrying out a community-based research project. The primary issues that arose in relation to this study were access to the community, power, communication, shifting research plans, timelines, the scope of work, and the required range of knowledge.

One of the issues which I had to consider with both CBR projects was the issue of whether or not I was truly working with the community. Given that the goal of CBR is social change that leads to social justice, it is important to work as close to the community as possible. This can be difficult to achieve at times since it may be challenging to find a grassroots organization with which to partner. Also, what Strand et al. (2003a) define as mid-level organizations are often better equipped to partner with university researchers. When I was working with John Brewer and Maria Swenson, since I realized that I was not working directly with the community, I did make an effort to bring the community into the research process as often as possible.

Regardless of whether the researcher partners with a mid-level organization or with a grassroots organization, in every CBR process the researcher needs to be aware of the issue of power. It may not always be something that hinders collaboration, but the dynamics of power are always present. In my work with the Coalition, my lack of power interfered with my ability to develop a collaborative relationship. When working with John Brewer and Maria Swenson, as is typically the case with community-based research projects, I had to be more aware of the power I held as a researcher and make sure that our work together was based on shared decision making. As the researcher gets closer to working with the actual community, issues of power become even more significant. If community members are not allowed any power in the CBR process, it is less likely that they will become empowered through the work that is completed.

Communication can be significant in making sure that all participants in the CBR process are being heard. Strand et al. (2003a) point out that in order to communicate effectively, researchers need to make sure that they are not talking in inaccessible jargon and that they are actually listening to the people with whom they are partnering. In my experience during both case studies, communication was the primary issue in determining whether I was able to develop a successful collaboration. When working with the Coalition, it was less an issue of making sure that I listened to my community partners than it was an issue of not feeling heard. However, I was at fault in not establishing a pathway of communication from the beginning so that we could all be heard. When working with John Brewer and Maria Swenson, communication allowed us to create quality work together and work past any disagreements.

Communication is also valuable in working through the shifts that are endemic to carrying out this kind of work. Regardless of the plans that are laid out in the beginning, changes will occur. The researcher and community partners need to be fluid and flexible to accept and address these changes. Sometimes, the research cannot be carried out as originally planned for a variety of reasons, and the collaborators will not always able to complete projects as envisioned. This occurred in my work with the Coalition in relation to the community indicators, as well as in my work with John and Maria in relation to the demographic project. In these situations, the researcher will have to work closely with the community partner to determine if there is a way to achieve the same results or access the same information through other means.

Adapting to these shifts in the original research plan can impact the timeline of the research, as can other factors. Dealing with timelines is an issue in any community-based research project. The reality is that a successful collaboration that includes the community in all aspects of the process of creating knowledge takes time. Regardless of how quickly your community partners respond to your request for input, the process is going to take longer than if the researcher is working on his or her own. The timeline can also be impacted by the fact that most community members have other obligations and cannot devote all of their time to the research. In some cases, the researcher is the one who has to keep the research project going and keep the process moving along in a timely manner. In other situations, the community partners may have expectations that the work will be completed sooner than is feasible, particularly if the community partners have not had experience with research.

Community partners who have not had experience with research may also have unrealistic expectations about what the researcher should be able to accomplish. The scope of the work is an issue that the researcher needs to consider carefully when determining the research that will be pursued. My tendency is to over commit and regret it later. The researcher should start small and allow the research to expand if time and resources allow. This issue becomes less of a factor when the community is involved closely in the research process. If the community is also completing the research, they will have greater understanding of the time consuming nature of the work.

Another issue that can impact both timelines and the scope of work is the fact that the community may decide to pursue research in an area with which the researcher is not familiar. According to Strand et al. (2003a),

Researchers often find that they must develop expertise about a range of topics that lie at least somewhat outside their area of training, and in some cases, a project may require technical expertise from a number of different disciplines (p. 78).

An example of this from the research I conducted was the demographic research that I pursued with John and Maria. I knew nothing about demographics and neither did my community partners. I spent a considerable amount of time accessing information about demographics just to get started. Once I had a sense of what I was going to do with the project, I began pursuing the data. At that point, I realized that I would not be able to complete the project as originally envisioned. Because of the fact that I am not familiar with demographics, I have had difficulty conceptualizing how to pursue data in a different way. When researchers pursue research in a new area, they have to learn along with the community, which can take time. In some ways, however, this puts the researcher and the community on the same footing, since the researcher and community partners are both teachers and learners (Strand et al., 2003a). This could potentially make some researchers uncomfortable if they are used to being seen as the expert.

The second sub-question of the study is-What facilitates or hinders the process of collaboration? Most factors that facilitate the process of collaboration can also be hindrances, depending on how they play out. I define a hindrance as a factor that obstructs or impedes the development of an effective collaboration. However, some factors only facilitate collaboration and some factors can only be a hindrance.

One important factor that facilitates collaboration is determining the goals of the research at the beginning of the collaboration through the use of dialogue. According to Verbeke and Richards (2001), "Shared goals are critical to a successful collaboration. Shared goals make it possible for a collaboration to succeed, even under adverse conditions and unlikely pairings" (Shared Goals section, para. 1). If the researcher and the community are not able to agree upon goals, then they will not be able to move into the beginning stages of the research process; that is to develop research questions and a research plan. This factor was a significant hindrance in my work with the Coalition. Since we did not define shared goals at the beginning of our work, we had no direction for our research.

This initial dialogue is not only important for developing shared goals, it is also essential to the process of developing relationships (Reback, Cohen, Freese, & Shoptaw, 2002). As Stoecker (2002a) points out, relationships are integral to collaboration. If there is a relationship between the researcher and community, trust can emerge which will lead to open and honest communication. However, trust is not something that happens quickly or easily. It develops as the relationship continues to grow. The growth of the relationship is strengthened through showing consideration for each other. This signals to the partners that each realizes that the other is an important part of the collaboration.

The development of a relationship is facilitated by taking time at the beginning of the collaboration to define the roles and responsibilities of all the participants. A memorandum of understanding (MOU) that defines these roles can be useful. According to Nyden, Figert, Shibley, and Burrows (1997), "an up-front written agreement can be helpful...to provide an opportunity for both researcher and practitioner to think about and discuss their relationship before a research project is under way" (p. 5). This type of document can help reduce power struggles because it specifies responsibilities (Strand et al., 2003a; Verbeke & Richards, 2001). It also requires that the participants put their shared goals in writing; thus it creates a document that aids in reminding the participants of what they are working towards. Developing this type of document can be useful as well in ensuring that all the participants are choosing to participate in the process. If anyone is feeling coerced into participating, this would probably come forward during the creation of the memorandum of understanding. Using this type of document in my work with John and Maria helped create a more successful collaboration.

Through the process of developing a memorandum of understanding, it will become obvious how all of the participants view the use of data. Views about the uses of data can be a significant factor that can either facilitate or hinder the collaboration. The researcher and community partner need to have extensive dialogue as they clarify goals in order to make sure that there is agreement about the purposes of the data that are being collected. The community partner's previous experiences with research can influence how they view the use of data. Though data can be used for many purposes, all parties need to agree on how they will be used in that particular context. Conflicting views about the use of data was a significant impediment to my work with the Coalition. However, when working with John and Maria, our compatible views about research helped to facilitate our work together. Since most researchers are influenced by the paradigm of traditional academic research, those conducting CBR will need to consider how this paradigm can be integrated successfully into CBR work.

The community partner's previous experience with research can also influence the value they place on the researcher's knowledge and vice versa. In my work with John and Maria, the fact that they both understood the research process meant that they had greater appreciation for my skills. I also had greater value for their input since it was based in research experience. However, if the researcher is working closely with the community, it is very likely that most community members will not have had much experience with research, except maybe as the subjects of research. In this case, though the community does not have knowledge of the research process, they do have knowledge of the community (Strand et al., 2003a) which the researcher needs to acknowledge and value.

A factor that impacts the ability to develop regard for each other's knowledge relates to personalities. Personalities can be either a significant help or significant hindrance in developing a successful collaboration. Things work best when the researcher and community partner develop rapport based on compatible ways of interacting and compatible views of the world. However, if there is not this rapport, then it is imperative that the researcher develops the personality traits of patience and flexibility in order to work through difficulties that arise in the relationship. One of the factors that impeded my collaboration with the Coalition was that Lisa and I were not able to develop rapport. I was still in the process of developing the necessary skills to support a successful collaboration and was not competent in overcoming the issues that developed around personalities.

Finally, a factor that is often a hindrance in developing an effective collaboration is the issue of hidden agendas (Verbeke & Richards, 2001) or fluctuating agendas. If there are hidden issues between community members with whom the researcher is collaborating, this undermines the collaboration. In my work with the Coalition, I felt that there were issues relating to Lisa's power in the organization which I became aware of toward the end of our collaboration. If I had been aware of these power issues at the beginning, I would have approached the situation differently. Also, partly because we did not determine shared goals at the beginning of the collaboration, there were constantly fluctuating agendas in relation to the research that we decided to pursue. At the same time I was dealing with hidden agendas and fluctuating agendas, I also had my own agenda which was to complete my dissertation. Since this agenda did not benefit our CBR work, this also impacted our collaboration.

The third sub-question of this study is-What does the researcher gain through this collaborative process, and what are the benefits for the community?

As the researcher in this process, I felt I had gains of both knowledge and other less tangible rewards. One of the reasons that I continue to be interested in pursuing community-based research is that this work provides me with a sense of purpose. I feel that I am doing something beneficial for the community in which I live. This sense of purpose is important for me as a doctoral student, but I think it will be even more important when I begin working as an assistant professor. According to Stoecker (2001), "One of the most important concerns among those in higher education at the dawning of this new millennium is the degree of disenchantment so many academics feel with our institutions and our disciplines" (p. 14). I do not want to be in the position of having worked so hard to get to this destination to find that it has no meaning for me. I feel that participating in the community is something that will provide meaning and a sense of purpose to my work.

Some of the emerging literature about community-based research points to the idea that students gain a sense of empowerment through participating in this kind of work (Willis, Peresie, Waldref, & Stockmann, 2003). I do not know that these experiences empowered me, primarily because I already knew that I have the ability to create change. This knowledge comes from previous experiences in my life as a Peace Corps volunteer and as a teacher. What I am still working on is trying to find my place in the world. What gives meaning to my existence is the potential to make things better for my fellow human beings. I am just trying to determine the best way to do this. Accordingly, carrying out this type of research feels like the right direction for me.

Along with providing a sense of purpose to my research, this kind of work is also engaging for me. I enjoy collaborating with people on projects and I find that I am more fully engaged when I collaborate. As Verbeke and Richards (2001) point out, "One could argue that, as social creatures, human beings are predisposed to collaborate" (Process section, para. 5). When I am collaborating with other individuals, I feel like the work that is produced is always of a better quality than what I could do on my own. This is not an indication of a lack of self confidence in my abilities, but rather a realization that the work that is produced through a collaborative process incorporates the knowledge and expertise of all of those involved and is, by definition, a stronger product.

Along with the relational rewards of conducting community-based research, there are also other more concrete benefits. Through conducting both of these case studies, I significantly expanded my knowledge base. I developed knowledge in research areas which I knew nothing about, such as demographics, and I also developed additional research skills. In my work with John and Maria in designing surveys, I gained significant knowledge about how to construct an effective survey. Also through my work with the Coalition, I gained knowledge about urban education, and I also developed the skills for designing an evaluation plan. Though the course work that I completed through my doctoral program provided a foundation for this work, the actual experience of carrying out research has provided the greatest learning opportunities for me.

In my work with both projects, I developed greater knowledge of different peoples. When working with the Coalition, I was exposed to the inner workings of the non-profit world and got a view into the dynamics of working with these kinds of organizations. When working with John and Maria, I developed greater knowledge and understanding of the issues that immigrants deal with along with learning cultural knowledge about the two primary immigrant populations with which John and Maria work. I think these experiences helped add to my ability to work well with different people.

Along with the benefits that the researcher gains through conducting community-based research, it is also important that the community benefits as well. One thing that the community gains is research skills. According to Hills and Mullett (2000), "Effective community-based research focuses on gains to the community through both the results and the research process itself" (p. 3). Through the work that I carried out with John and Maria, they gained knowledge of how to design surveys, and John gained knowledge of how to use SPSS, how to analyze survey data, and how to structure the information in a report. They will be able to use this knowledge to conduct research on their own in the future.

In addition to gaining research skills, the community also gains useful research results that they do not always have the time or expertise to collect on their own. These research results might be used to improve a program, to seek out funding, or to provide evidence to funders that a program is providing the services it is required to provide. As Stoecker (2002a) points out,

They need research, whether it is for a grant proposal or a court case or a policy proposal down at city hall. Sometimes it is research they are perfectly capable of doing themselves except that they don't have time. Sometimes it is highly technical research they don't have the time to learn or the equipment to carry out. Sometimes they just need a document that has a 'PhD' on it (p. 2).

In my work with the Coalition, I provided information that helped lay a foundation for subsequent work. However, when working with John and Maria, I provided information that they can use now to improve the program and potentially access resources.

Another benefit that the researcher can provide is access to resources and expertise. Since both my advisor, Dr. Darby, and Dr. Green were supervising me in both of these projects, I had access to their knowledge in completing this work. I called upon their knowledge frequently during both projects. I also connected John and Maria to resources in relation to community organizing. They now have a contact, Manuel Alvarez, whom they can call on to assist in continuing the process. Manuel has already agreed to come out for several days in the summer to continue working with the community. I also connected John and Maria to some financial resources as well. I applied for and received a scholarship to help fund some of our work, and my advisor also provided financial support through a grant that he had that was directed toward community-based research.

Finally, the most important benefit that the community can gain through the process of CBR is change. Though the work I completed with the Coalition did not lead to any change that I am aware of, the work that I completed with John and Maria has the potential to lead to significant change both within the English program and within the community as a whole.

When considering the final research question of the study-What can we learn from these experiences to inform the field of community-based research?-the most significant thing that I have to offer is a way to conceptualize how to get the most value from a CBR project. The conceptual model of CBR that I have designed is based on the analytic framework that was introduced in chapter three and incorporates the continuums included in Figure 1 (p. 63). As you move out toward the positive on each point of the continuum, the work has greater value. When I say that the work has greater value, I mean that it has greater value for the community. I define value as the potential to empower community members who are participating in the research process as well as the potential to bring about beneficial change for the community. I position Stoecker's (2003) construct of radical CBR as the form of CBR that has the most value in that it has the greatest potential to empower community members, and it has the greatest potential to create substantial change. Mainstream CBR also has value, but has less potential for significant change. As you move toward the center of the model, the value of the work decreases. See Figure 3.

Figure 3 Conceptual Model of CBR

Though Stoecker (2003) points out that the underlying theoretical foundations of mainstream CBR and radical CBR are in some ways contradictory, in my conceptual model, mainstream CBR is imbedded within radical CBR. I see CBR as a continuum of practices with radical CBR as the goal, as it has the greatest potential for empowerment and change. This model provides a way to conceptualize the things that need to be in place to support greater value in CBR work. For each continuum within the model, the researcher must make a decision about how to create the most value for the work being conducted. In order to understand the model more fully, it is important to consider the four continuums that are incorporated in the model.

In relation to the construct of community, the goal is to work with those who are marginalized or disenfranchised. This typically means collaborating with a grassroots organization. If the researcher is unable to locate a grassroots organization, the options are to assist in the process of creating a grassroots organization or to partner with a mid-level organization. Working with a mid-level organization means that you move inward on the continuum toward mainstream CBR, and the work has less value; however, this can be counteracted somewhat by using the mid-level organization as a means to facilitate community involvement in decision making during the research process (Strand et al., 2003a).

The goal of collaboration is shared decision making throughout the CBR process which leads to the development of lasting and positive relationships between university partners and the community. These relationships are developed through communication and can be hindered by issues around power and lack of trust. If the collaboration is not successful, there is less potential for change, and the work therefore has less value.

One of the most challenging goals to achieve in pursuing the radical model of CBR relates to the creation of knowledge. The goal is full participation of the community in all aspects of knowledge creation. As Stoecker (2002a) points out, "The highest form of participatory research is seen as research completely controlled and conducted by the community" (p. 9). This can lead to empowerment for the community through the democratization of knowledge. However, full participation can be difficult to achieve, particularly if community members do not have the time to participate in all aspects of the research. The greater the participation of the community in creating knowledge, the greater the potential for empowerment. Therefore, the researcher is obligated "to do whatever is possible to enhance participation" (Greenwood, Whyte, & Harkavy, 1993, Our View section, para. 8).

The further the researcher moves toward the positive on the continuums of community, collaboration, and knowledge creation, the greater potential there is for change. The goal for change is change that "transforms the structure of power relations so that those without power gain power" (Stoecker, 2002b, p. 232). If the researcher is partnering with a mid-level organization, it is more likely that the change that will be accomplished will be primarily programmatic change. Though any change is important in that consistent small changes can lead to greater overall change, limited programmatic change has less value within an individual CBR project.

It is important to consider why it is essential to reach for the radical model of CBR since this model may not be as compatible with higher education as is the mainstream model of CBR (Stoecker, 2003). If the goal of CBR is truly social action and social change that lead to social justice, then it is imperative that we pursue the radical model. As Freire (1970) states,

The radical, committed to human liberation, does not become the prisoner of a 'circle of certainty' within which reality is also imprisoned. On the contrary, the more radical the person is, the more fully he or she enters into reality so that, knowing it better, he or she can better transform it (p. 21).

Existing realities point to the need for significant changes in our society. As Stoecker (2003) points out, the gap between the wealthy and the poor is continuing to widen, and economic and political decisions are being made primarily by the wealthy. As Stoecker says, "The only way for the poor to gain a seat at the table, then, is for them to counter the power of money with the power of numbers" (p. 43). If we want to expand democratic participation to include those individuals who have been excluded because of lack of economic and social capital, we need to push for radical changes. These kinds of radical changes call for a radical model of research.

If we push for a radical model of CBR, some faculty and students who are interested in pursuing CBR projects may feel that it is impossible to achieve this goal and thus decide not to pursue community-based research at all. As Strand et al. (2003a) point out,

We caution the current or would-be practitioner against becoming paralyzed by imperfections from these ideal principles, acknowledging that no CBR practice is perfect in its design and execution and that at some level, we need to do the best we can under our current circumstances (p. 74).

I agree with this statement, and I feel that conducting mainstream CBR is better than not pursuing CBR at all. However, I do think that those who carry out community-based research should consistently seek to pursue a more radical form of CBR that has the potential to bring about greater change.

This study has several implications for the field of CBR. First of all, it provides a view into the process of conducting this kind of work. It allows the reader to vicariously experience the issues that arise when conducting community-based research and the factors that facilitate or hinder a successful collaboration. By exploring the missteps I made during the first case study and how I addressed some of these missteps during the second case study, a research practitioner who is considering the use of CBR may be able to learn from my experiences.

This study also demonstrates the importance of developing interpersonal skills that relate specifically to this work. As a student practitioner conducting CBR, I lacked the requisite skills in my work with the Coalition to establish a relationship at the outset of our work, and I also lacked the requisite skills to deal with the issues that arose in order to address these conflicts. My experience points to the need to develop course work for students who plan to participate in CBR projects that focuses on strategies that can be used to deal with the interpersonal dynamics that can arise in CBR work.

Though Strand, Marullo, Cutforth, Stoecker, and Donohue (2003a) have laid out the beginnings of an epistemology of practice in relation to CBR, there is a need for more clearly identified standards within the discipline. These standards could include offering more clearly delineated guidelines for the stages of the CBR process and what the researcher should do to make each stage successful. These standards could also address the issue of how to pursue data that are considered valid and reliable by traditional academic standards yet at the same time still serve the needs of the community. Another area that needs to be addressed that was present in both CBR projects that I carried out was the idea of subjectivity within CBR projects. Since CBR work is inherently a subjective process, the field should begin to develop an epistemology of subjectivity in order to address the role of subjectivity in CBR work.

One of the issues that arose in my work with the Coalition was conflicting views about the use of data. Part of this conflict stems from the fact that my background in research is traditional academic research. I recognize the value of traditional academic research in providing standards of quality for research and I also recognize the importance of this type of research as a resource for CBR practitioners in the field. However, in my CBR work, there were times that my views of research conflicted with those of my community partners. The field of CBR needs to determine how these two research paradigms can coexist within CBR work. This is an issue that will need to be addressed within individual CBR projects as well as within the university. CBR practitioners will need to begin to define their place within the academic community.

As G. Lichtenstein (personal communication, June 8, 2004) pointed out, there are three possible approaches that CBR practitioners could pursue in seeking to make a place for CBR in the academic community. The first approach is a competing paradigm: CBR versus traditional academic research. In this approach, CBR researchers seek to position CBR work as the principal form of research within the university and shift the focus of the university toward social change. The second approach is a coexisting paradigm. In this paradigm, CBR work has more of a subsidiary role in the university. The results of the work are valued, but the methodology is not considered to be academically rigorous. The third potential approach is an integrated paradigm. Lichtenstein says that within an integrated paradigm,

CBR strives to integrate traditional research goals and goals of community change. CBR relies on traditional methodology (quantitative and qualitative), but also rejects assumptions of objectivity leading to its own epistomology and methodological discipline and safeguards. CBR faculty seek to expand academic notions of what constitutes effective research.

As more faculty begin to consider implementing CBR projects, it will be important for faculty members and universities to determine the role of CBR within the institution.

Finally, this study provides a way to conceptualize CBR work so that the researcher can work toward a collaboration that has the potential to create the greatest value based on the goals of empowerment and change. The conceptual model that I designed, based on the current literature about CBR (Stoecker, 2003; Strand et al., 2003a), provides one way to consider how to design and evaluate CBR work. Like any model, it is not perfect, but it is the best explanatory model that I can provide at this point based on the research that I have done.

Based on some of the questions that arose when I was conducting my research and some of the limitations of my study, I have four recommendations for further research. First of all, it would be beneficial to conduct research that explores the experience of conducting community-based research through the eyes of the community. Though I interviewed my community partners and tried to incorporate their insights into my study, my study primarily focuses on the researcher's perspective of this experience. Community members who participate in CBR projects may have different ideas about the issues surrounding this kind of work, and greater perspective on the community's experience would assist in developing an epistemology of practice for CBR.

One of the concerns that was raised by my community partners John Brewer and Maria Swenson related to the quality of the data. I believe it would be beneficial for a researcher to explore the research that is produced in multiple CBR projects and determine whether the work is quality work based on both the traditional standards of quality (in relation to validity and reliability) as well as the perceptions of the community as to what they consider to be quality work. If community-based researchers can demonstrate to the academic community that community-based research produces quality research, it is more likely that CBR will become widely accepted within the academic arena.

Along with exploring the quality of data, it would be interesting to conduct long-term case studies to explore the impact of CBR projects over a period of time. I was able to do this somewhat with the first case study I pursued; however, that research project appears at this point in time to have had minimal impact. It would be more interesting to study the long-term impacts of my work with John Brewer and Maria Swenson, particularly in relation to the community organizing piece. Again, if researchers can demonstrate that CBR work does bring about important change, it may convince some academics to pursue this work.

Finally, the case studies that I presented here were case studies of conducting mainstream community-based research. It would be interesting to read about the experience of conducting radical community-based research. Though it seems likely that many of the same issues would arise in this work, there may be other interesting issues that would emerge that would lead to a different conceptual model of CBR.

As I carried out both of these CBR projects, I continued to ask myself why I should pursue this work. The answer lies with the fact that I believe that my role in the world is to make life more livable for the human beings that surround me. My life has meaning through what I am able to give to others. I also believe that my liberation is bound up in the liberation of everyone around me who is marginalized and excluded from living a life of opportunity. My goal is to be able to carry this personal philosophy into the career that I pursue.

I believe that we, as the "educational elite" of this country, cannot allow injustice to run ramshackle around us without some attempt to create equity. In order to be able to do this, there needs to be a place for CBR work in the university setting. Though traditional academic research will always play a role in academia, I believe that universities need to recognize their role in becoming agents of change versus agents of esoterica. In the end, what matters is the difference we all make in the world.

|

Contents | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Notes & References | Appendices |