| COMM-ORG Papers 2003 |

http://comm-org.wisc.edu/papers.htm |

The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

&

The Logan Square Neighborhood Association

Prepared by

Suzanne Blanc, Ph.D.

Matthew Goldwasser, Ph.D.

Research for Action

&

Joanna Brown

Logan Square Neighborhood

Association

February 2003

© Copyright 2003 by

Research for Action

3701 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

www.researchforaction.org

Telephone (215) 823-2500

Fax (215) 823-2510

Research for Action (RFA) is a non-profit organization engaged in education research and reform. Founded in 1992, RFA works with educators, students, parents, and community members to improve educational opportunities and outcomes for all students. RFA work falls along a continuum of highly participatory research and evaluation to more traditional policy studies.

(Note: This reflective note was written by Sukey Blanc and Joanna Brown. Sukey is the team leader for the Research for Action (RFA) team that worked with the Logan Square Neighborhood Association (LSNA). She has been involved with this project since the winter of 1999. Joanna Brown is the education organizer at LSNA who coordinated LSNA's participation in the project.)

Introduction

Sukey: I first learned about LSNA in the winter of 1999 from a colleague who told me that LSNA, a multi-issue community organization in Chicago, needed a research group to document their work. She thought that the styles and interests of RFA and LSNA would mesh well together.

Research for Action has a history of, and a commitment to engaging in collaborative, participatory research. By collaborative, participatory research, I mean an approach in which professional researchers and the organization or people being studied jointly construct the research questions, identify appropriate research activities, and work together to interpret and present findings.

During our first phone conversation with LSNA, Nancy Aardema (LSNA’s executive director) and Joanna Brown (the lead education organizer) were clear that the research needed to be a collaborative effort between LSNA and the documenter they selected. The MacArthur Foundation, which funded the project, wanted the research to meet the needs of the community as well as those of the foundation. LSNA’s organizational ethos also steered it toward a collaborative approach.

Much has been written about the value of collaboration and participatory research. Less has been written about the processes involved and the challenges that may arise. I hope that this joint reflection on our process, the benefits for both organizations, and the challenges we encountered will help others who undertake a similar task.

Special thanks to my friend and co-author, Matthew Goldwasser. Matthew joined this project in the winter of 2001. Like me, he is committed to doing collaborative, participatory research. He is also interested in sharing what we have all learned from this experience and therefore spurred Joanna and me to produce this reflective piece. Matthew himself has worked very closely with LSNA's housing leaders, shared their fears and their joys, read their writings, and engaged in extensive dialogue with them about earlier drafts of this report.

Developing a Collaborative Relationship

Sukey: During our first conversation, I found out that Joanna, who was also working on her doctorate, would be playing a central role in the research. Joanna has been a key liaison for RFA—setting up interviews with people who could help us understand LSNA’s foundations and introducing us to everyone as friends of the organization. She has also been involved in every aspect of the project, including working on data analysis and writing.

Others at LSNA have also been consistently friendly and welcoming. It was especially helpful to me that everyone had faith that I could communicate in Spanish, even though my Spanish is far from fluent. Whenever I was in Logan Square, I found myself switching into Spanish, or a combination of Spanish and English, and that was definitely one of the things that made me feel like part of the LSNA community.

Benefits of Collaboration

Joanna: The RFA/LSNA research collaboration was useful to LSNA in a variety of ways. There were a number of things which we, at LSNA, would probably not have done on our own, but which we did do because of our work with RFA.

First, RFA provided some funding for community-based research which made it possible to re-survey the neighborhood about the community learning centers. We were already familiar with this kind of community-based research, as parents had surveyed each school's neighborhood before establishing a community center. But Sukey asked us about what questions we would like to have answered, and encouraged us to do follow-up surveys about the community centers. The information we gathered from these surveys has helped us to keep our centers fresh and to resist the bureaucratization that creeps in as institutions become routinized.

Second, because RFA staff made it clear that they were interested in using the voices of LSNA leaders in their report, LSNA people were prompted to collaborate in a variety of ways, from befriending and educating Sukey and Matthew about LSNA to writing reports on housing meetings and poems about marches.

Third, we ended up with some concrete products that can be used both inside and outside the organization. An outstanding example is the "Real Conditions" booklet written by parent mentors at Mozart School. RFA paid for the writing workshop and the booklets as part of the process of collecting first-person materials for the report. The writers have read their work at school potluck dinners and assemblies. The book has also been used in ESL classes and to help funders and other outsiders understand LSNA's work.

The intermediate products of the research were probably the most useful to the organization – an article that Sukey wrote for our newsletter, the women’s writing project, and the Education Indicators project report on LSNA (a collaboration between RFA and the Cross City Campaign for Urban Education), with its many pictures. It would be useful to mine long research reports for shorter segments that could help publicize the organization.

Joanna: As with any documentation of an organization, this one began at a certain point in LSNA’s history. RFA's willingness to collaborate with us in thinking through the research enabled the RFA team to learn more about and take into consideration the organization's history and the participants' memories. By working closely with LSNA, RFA researchers were able to frame the questions and the report in a way that made sense to us. Because they were open to our perspective and viewed us as colleagues, we were able to help the researchers focus on and adjust the context in which they saw our work, even as they brought a fresh and independent analysis of LSNA's work.

Sukey: Each partner brought perspectives which challenged the other’s way of interpreting LSNA and its work. Creating a sense of shared meaning between RFA and LSNA has been a process of dialogue and struggle. There was always good will and trust, but the researchers often did not see things in the same way that people inside the organization did. It seems like every time we presented data and our analysis to them, they said, "Well, no. Here's a different way of looking at it.” That definitely enriched our understanding.

After we completed our first round of data collection, Joanna visited us in Philadelphia. Our conversation was pretty intense. We kept asking questions like whether LSNA was confronting the culture of the schools. Meanwhile, Joanna was pushing us to have a better understanding of LSNA's approach to relationship-building. When I think about it, we were dealing at that very first meeting with issues that we've continued to deal with. We've talked a lot about issues of power and power inequities, even though we didn’t always refer to it that way.

Joanna: We were

able to help shape the frame through which RFA examined our work. Take Sukey's

appropriate and challenging question: "Is LSNA confronting the culture of

the schools?" It is not that the question was wrong – LSNA needs always to challenge itself

on this question –

but our conversations shifted the framework within which that question was

asked. We were able to bring to this discussion an historical perspective of

how far the schools had moved since LSNA began organizing with parents. When RFA

arrived on the scene, LSNA was already far into a process of transformation

which had shifted, though not revolutionized, the power relationships within

the school and increased the amount of social trust.

Joanna: Because of RFA's commitment to collaborative research, RFA staff insisted on discussing drafts of the report in feedback sessions with a variety of people, from school staff to parents and LSNA housing and education leaders. This led to interesting and lively discussions about LSNA's work with a diverse group of LSNA leaders and staff who normally would not meet for that purpose. These sessions gave leaders a chance to reflect on their work and how it may be perceived by a broader intellectual community. Having a written document to react to provided a focus for the relatively abstract discussion.

Challenges of Collaboration

Sukey: One of the things that I've learned is how hard it is to do participatory research. When I wrote the proposal, I had hoped that the community survey process would lead to community research teams whose questions and findings would intersect with the questions and findings of the outside researchers. What I found was that it was a lot harder than I had anticipated to combine the work of the two organizations – the research approach of outsiders and the inside voice and knowledge of people in the community. Nevertheless, it remained a disappointment to me that the community survey process couldn’t be integrated into the final report in the way that I had envisioned.

Joanna: I think the limits to our collaborative research which Sukey refers to had more to do with the time demands on the staff of our organization than anything else. Everyone is always extremely busy. I was the point person for the collaborative research, was never freed up from other responsibilities to work on research, and was always overextended. Since this will usually be the case with community organizing staff, it is often helpful to have research staff develop the research plan and materials (such as survey instruments) and then ask organization members to implement them.

It is in the nature of community organizing that the practical and immediate demands of our work tend to push aside and overtake the longer-term or more abstract demands. We are very glad that we now have a final product that tells LSNA’s story, but at any particular moment during the research process, data collection usually seemed less urgent than the next issue or meeting.

Sukey: Part of the difficulty of collaborating came from the geographic distance between Chicago and RFA’s home base in Philadelphia.

Joanna: Because of the different time frames that researchers and organizing staff operate under, I would agree with Sukey that it is important to have a local researcher (in addition to someone on staff who is collaborating) to provide structure for the data collection on a day-to-day or week-to-week basis.

Concluding Comments

Sukey: When I think back on the first Congress that I went to, I remember feeling that the event was grounded in people's real lives. It was smaller than the other Congresses I have attended, with about 200 people, and it had an arts emphasis. It felt to me like people in LSNA were engaged in creating a new kind of community. When we met with LSNA to give feedback about the early stages of the affordable housing campaign, we had a similar impression. We could tell that people on the housing committees really cared about each other. The issues were important, but the caring that they had for each other was at least as important.

I think that the biggest thing I learned from this project was thinking about how change looks from the inside, from the perspective of people who are creating that change. Even though I started out with a commitment to collaborative and participatory research, I started out thinking more like a social scientist, assuming that my writing would emphasize the social and economic structures that shape the Logan Square community. Instead, I found that individuals’ stories and their growing sense of ability to take control of their lives seemed to be the central theme of this work.

My hope is that foundations will gain some new ideas from this report about how community organizing can function to build community capacity. Much of what we talk about in the report involves building trust within and across groups, but you can't build trust in poor communities without confronting power inequities. Capacity building thus involves both creating community and addressing power issues.

LSNA’s work over time shows us the challenges of combining relationship-building in a diverse community with addressing issues of power. Nonetheless, it looks to us like LSNA has managed to fulfill both, as we have seen in their work on school reform and affordable housing. I hope that this report gives others some models of how community organizing can both confront power issues and also create community.

Joanna: Collaborative research can take many forms, but in general, whether it be writing and research by community members or discussion and debate over research questions and theoretical framework, research can only benefit from collaboration and respect between researchers and subjects.

Sukey and Matthew took collaboration seriously. And people knew that. They became part of the LSNA family, free to walk in and out of meetings and events without causing a stir. They saw things from the “inside” and saw processes, relationships and strategies develop. I feel that they gave us several years out of their work lives, and thank them for their commitment to telling our story.

Introduction

This report presents a study of the evolution, implementation, and results of the work of the Logan Square Neighborhood Association (LSNA), funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. LSNA, one of the grantees under the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation's Building Community Capacity program, has a 40-year history of mobilizing neighborhood residents to maintain and improve the quality of community life and to bring additional resources and services into the neighborhood. LSNA's work is guided by its Holistic Plan, which includes improving local public schools, developing youth leadership, enhancing neighborhood safety, maintaining affordable housing, and economic revitalization.

Overview of the Study

Between May 1999 and July 2002, Research for Action (RFA), an independent, Philadelphia-based nonprofit, worked in collaboration with LSNA on this documentation project. Over the course of three years, the RFA research team worked with LSNA staff and leaders to collect and analyze data about LSNA’s internal processes, its strategies for neighborhood change, and the impact of engaging with LSNA on participants, especially in the areas of education and housing.

Overview of LSNA

LSNA, an organization with a staff of 18 in 2002 and a yearly budget of approximately $1,000,000, has remained flexible and intimately connected to the community. According to both staff and community leaders, during the past 13 years, LSNA has transformed from an organization made up primarily of white homeowners to a racially, ethnically, and economically integrated organization (reflecting the demographics of the neighborhood). Since 1990, LSNA has developed strong school/community partnerships, created a nationally-recognized affordable homeownership program, and built citywide visibility as a dynamic, community-based organization. Today, as low-income Logan Square residents face the possibility of displacement due to gentrification, LSNA is fighting to maintain the quality and diversity of community life it has helped to create.

LSNA’s executive director of thirteen years, Nancy Aardema, strongly believes that the organization's success has been based on building ongoing relationships of personal trust among individuals and organizations. During these years, the organization has looked hard for ways to nurture numerous and varied types of new social relationships within the Logan Square neighborhood. According to Aardema, these relationships become the foundation for strong neighborhood-based leadership and the capacity to challenge power inequities and bring about social change.

Relationship building is central to all of LSNA’s work. As the organization strives to maintain Logan Square as a neighborhood that is diverse economically, as well as ethnically, linguistically, and racially, Aardema believes that the campaign for affordable housing is worth undertaking only if it fosters creative, meaningful relationships. As Nancy says,

[Any campaign] has to be worthy of our time, both in terms of victory and building relationships. So part of our organizing is always relationship building and making it worth staying in the community because it's deeper than a house. It’s about relationships and creativity.

LSNA's successes in bringing together diverse members of the Logan Square community, mobilizing community members to address shared needs, and accessing outside resources all make it a valuable context for examining how a community organization builds community capacity by creating new sets of relationships, which in turn increase community well-being.

Community Change and Displacement In Logan Square

Logan Square covers 3.6 square miles located north and west of Chicago’s vibrant downtown. Between 1970 and 1990, the demographics of Logan Square shifted from a majority of residents of Eastern European ancestry to a majority population of first and second generation immigrants from Latin America. Today, Logan Square’s population of 83,000 remains a heterogeneous mix of Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, other Latin Americans, recent Polish immigrants, established white residents, and African Americans.

While the neighborhood is racially and ethnically diverse, its potential for maintaining economic diversity is threatened as real estate values and taxes rise, development escalates, and market forces encourage the conversion of affordable housing units into condominiums or luxury townhouses. Since the early 1990s, poor and working class families have had increasingly fewer options for living in Logan Square. Many middle class professionals, both Anglo and Latino, are long-term residents of Logan Square and contribute to the creative mix that makes up LSNA. In contrast, LSNA members often perceive wealthy newcomers as oblivious or scornful of their poorer neighbors who have helped to build the community as they raised families, made friends, and worked to improve neighborhood institutions.

An activist priest in the neighborhood describes the sense of loss experienced by working class residents who no longer feel at home in their own neighborhood.

When the community begins to change, it is not just the houses. Suddenly “we” need more green space, more play space. Each time they go and tear something down, they say drug dealers lived there. There’s a feeling that now “we” deserve a park more than [someone] deserves a home. When the neighborhood begins to change, then the meaning of the neighborhood begins to change. (Father Mike, Catholic priest and housing activist)

In the fall of 2001, an organizer for LSNA’s Parent Mentor program, which trains parents to work in Logan Square schools alongside the classroom teachers, vividly described the heartlessness of incoming developers and the impact that displacement is having on her school and community.

I had 6 parent mentors living in one apartment building (it was a 17 unit building) and they got a 30 day notice and they were offered $2000 to be out in 5 days. These people started construction even before the 30 days were up. There were no permits issued, nothing. They were just told to leave. And not one of those families came back to Brentano. So we lost 17. I lost all those parent mentors. I lost a few friends. The fact they were able to do this; they weren’t issued any permits and when they were, they were back-dated. I look at the parent mentors we lost, the children we have lost from the school, the rental units we lost, and the lack of aldermen caring about those people, and even back-dating the permits! That all ties into what we’re up against.

As existing neighborhood bonds are threatened, LSNA struggles to stabilize the diverse community that it has helped to create.

Democratic Participation in Setting the Agenda for LSNA

All of LSNA’s activities are guided by its Holistic Plan, which is revised annually. The initial version of the Holistic Plan, completed in 1994, presented a positive vision of the community and provided a roadmap for all the different activities that started springing up when Aardema became Executive Director. One of the original writers of the plan told us,

As we continued to get victories in different areas, we just began to realize that we couldn't be everything at once…So what we did was, we brought the community together…We finally realized that we were just running all different places at the same time. And we needed some kind of filter.

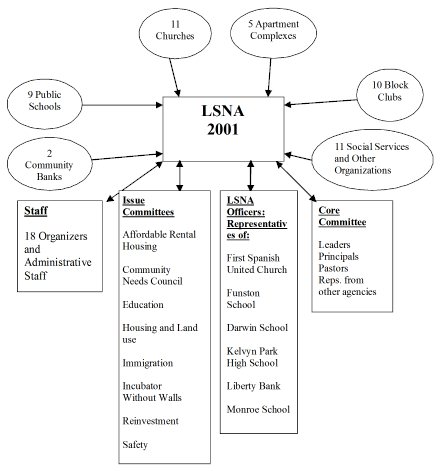

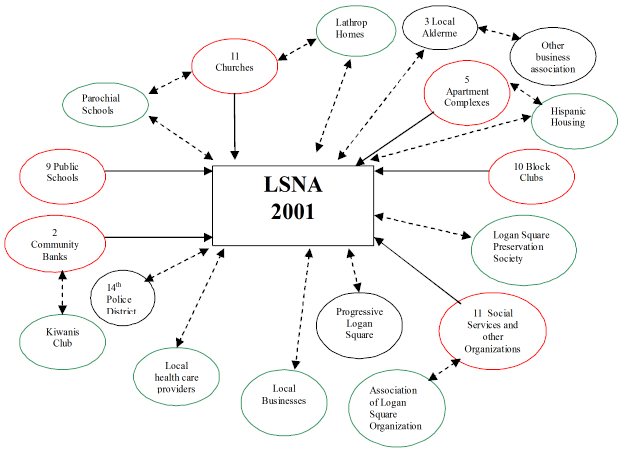

Thirty-four local schools churches, businesses, block clubs, social service agencies—with seniors and youth, parents and teachers, pastors and residents—worked together for over two years in small committees and large groups to set forth a specific agenda for building a healthier and more stable neighborhood. Committees were formed for different issue areas. Each year a “Core Committee,” appointed by LSNA’s elected Executive Board and leaders from each issue committee, engages in a process of brainstorming, visioning, and reflection that leads to an annual revision of the Holistic Plan. At the annual May Congress, the newly-revised Holistic Plan is presented and ratified by LSNA's Board (composed of representatives of LSNA's issue committees and representatives from almost 50 local organizations) and membership.

The elaborate process of holistic planning creates a well-defined democratic process which engages people in a civic arena in ways that many have not previously experienced. It teaches members new skills and provides a model which is replicated in other arenas within the organization. For example, as a Logan Square minister told us,

LSNA has been very active in [making schools] a center of community, not just a place where kids and a group of professionals descend…It is not just a place where you can depend on kids to receive an education, but also the place where you participate in the governance and deciding what goes on there and building it up and helping it grow.

Findings about LSNA’s Organizing Work in Schools and Housing

Finding One: LSNA’s robust school/community partnerships grew out of a sustained, successful campaign against school overcrowding in Logan Square.

During the period that LSNA was writing its first Holistic Plan, it was also leading a campaign against overcrowding in Logan Square schools. A parent and a former president of LSNA explained the hard work of organizing that enabled LSNA parents to win new school facilities for their neighborhood in the early 1990s:

There were many meetings with parents to prepare for going down to the Board of Education. What was funny was that no one would commit in a large group. But we went around and got individual commitments. We had many, many meetings. It was a year and a half of meetings. And then we finally all came together in one big room. You could feel the tension in the room. And once we started the meeting it was like, “Well, you know, so and so, you said that if so and so supported it, you will support it," and we would call on the names, “Well, are you here in support?” It was empowering because you finally beat this huge Board of Ed.

Over several years, the campaign resulted in five new annexes and two new middle schools. Just as importantly, the campaign both demonstrated LSNA's power as a community organization and built a foundation of mutual trust and respect among the principals, teachers, parent leaders and LSNA staff who had been involved in the campaign and witnessed the results.

Finding Two: LSNA’s school-based programs have been successful in helping hundreds of low-income parents take leadership roles in their families, their schools, and their communities.

LSNA’s Parent Mentor program, which trains low-income parents, often Latinas, to work alongside teachers in Logan Square classrooms, was initiated by one of the principals who participated in the campaign against overcrowding and who helped write the first Holistic Plan. Over 900 parents have graduated from the Parent Mentor program and have gone on to attain their G.E.D.’s, seek employment, and become active in the schools and the community.

Isabel, who is now a parent organizer for the program told us,

The program is great because it changes a lot of people's lives. Not only for myself, but when other mothers first get into the program, their self-esteem and everything is so low. When they first started, they were like really quiet; they would keep to themselves. And now you can't get them to shut up sometimes. I mean you see the complete difference, they really change their life. They are more outgoing. They are willing to do more for their kids. It's like night and day, they're so different.

The first group of parent mentor graduates initiated LSNA’s first Community Learning Center. Since then, parent mentor graduates have started five other Community Learning Centers, organized block clubs, and also initiated a health committee and an immigration committee within LSNA. The six community-controlled Community Learning Centers in Logan Square schools provide G.E.D. classes, ESL classes, and cultural and recreational activities for 1,400 adults and children every week. Parent mentor graduates and other community members also attend college classes leading to certification as bilingual teachers. Participants in and graduates of LSNA’s programs make up the backbone of community involvement in local schools, leading activities like principal selection, Local School Councils, and bilingual oversight committees.

Finding Three: Relationships established through LSNA’s school-community partnerships have led to substantial improvements in Logan Square schools.

Through parent participation in LSNA’s work in their children’s schools, parents begin to develop trusting relationships with each other and with school staff. These relationships lead to increased parent engagement in the life of schools.

As parents work closely with teachers, they develop a

better understanding of what actually happens in the classroom and begin to

develop their own educational aspirations. According to LSNA organizers,

school staff, and parents, when parents become more familiar with what is

happening in classrooms, they become more engaged with their children's

homework, reading to their children, and participation in activities like

Family Math and Family Literacy. The presence of parents in the schools also

creates new kinds of relationships between adults and children in classrooms,

leading to greater engagement by students in their classes.

Teachers and parents tell many stories of children developing new interest in

school because of parent mentors in their classrooms, seeing their own parent

in the school, or having the parent pay more attention to their children’s

schoolwork and learning. One parent mentor told us a common variation on this

theme.

To me, being a parent mentor means being able to communicate with the students as well as the teachers. And when you're able to share some of the things that you know about the subjects, it seems to bring out a lot of good in a kid. I've noticed that in certain classrooms that I go to, the kids, they want to participate even more, even the ones that weren't even really doing well. The teachers notice how well they're making progress because they're interested, and I keep their interest going.

Since 1996, all LSNA elementary schools have experienced significant increases in student achievement, even while the demographics remained constant. For example, from 1996 to 2001, the percentage of students at one school reading at, or above, the national norm on the yearly Iowa Test of Basic Skills rose from 17.5% to 29.3%. In math, the scores rose from 19.5% to 31.4%. Even more dramatic are the gains which occurred in the movement of student scores from the lowest to second lowest quartiles, a telling change because parent mentors usually work with the students who are most behind. These increases in test scores compare favorably with citywide averages, especially given the relatively higher rate of poverty and higher numbers of non-English speaking students in Logan Square schools.

Finding Four: During the three years of the documentation study, LSNA was able to develop a coherent and sustained organizing campaign for affordable housing.

As part of a citywide Balanced Development Coalition, LSNA asks elected officials to endorse a platform that would require all developers to set aside 30% of new housing units as affordable housing. Although few low- and moderate-income residents in Logan Square would benefit directly from the set-asides, LSNA supports this platform in the context of a broader campaign which includes new affordable homeownership programs, support for rental subsidies, property tax abatements, and advocacy for public housing residents. Participation in the citywide Balanced Development Coalition is a way for LSNA to strategize with people from across the city and produce public actions that challenge public officials and private developers to take a stance against rampant displacement.

Many other efforts by LSNA helped move this campaign forward between 1999 and 2002. These included: meeting with city officials to convince them to continue providing funds to subsidy rents for low-income families; holding public meetings to successfully block several undesirable zoning changes in Logan Square; bringing 500 community members together for a Housing Summit; and staging a mock funeral procession of several hundred people for lost housing in Logan Square.

In May 2002, we observed over 1,000 people at LSNA’s 40th Annual Congress loudly respond “Yes” to a speaker asking if they wanted to keep living in Logan Square and if they wanted to keep working for affordable rents. At the same event, school district administrators and state politicians publicly supported the need for affordable housing in Logan Square and the citywide balanced development platform. Most striking, LSNA’s newest alderman spoke about affordable housing on behalf of his fellow aldermen, promising to work closely with LSNA to ensure affordable housing in the neighborhood. This event contrasted sharply with the initial phase of the affordable housing campaign which RFA had observed three years earlier at the onset of our documentation project.

Finding Five: During the course of this study, a group of grassroots housing leaders emerged and coalesced to coordinate LSNA’s affordable housing campaign.

Many of the current leaders of the affordable housing campaign had originally approached LSNA to address their own immediate housing needs. As they developed relationships with LSNA staff and leaders, many newcomers to the organization began to connect their individual issues to a community-wide vision for affordable housing.

One example was Dawn, a recently separated mother who faced being forced out of Logan Square due to rising rents, but was able to qualify for a rental subsidy with LSNA’s help. Drawing on her anger over the injustice of unfair housing costs and policies, Dawn now speaks out for others who are struggling to find and keep affordable rents. Dawn told us,

When I first became involved with LSNA, I was a single mom and was suddenly going to have to pay the rent on my own. I was the last person to receive [the subsidy from the Low Income Housing Trust Fund] because the funds were used up. Knowing how much it would help me and other people who were in need of it, I agreed to work to keep the fund going. There is a subtle “class” intimidation out there that says, “If you’re on a subsidy, you have no right to speak for yourself.” Keeping involved was easy because [the housing organizer] treated me as her equal and we learned from each other.

Another housing leader, Roxanne, once homeless and a former resident of public housing, was able to buy half of a two-flat home for herself and her children through LSNA’s affordable homeownership. Roxanne now faces rising taxes and pressures from developers and is fighting to maintain her house and her identity as a homeowner. She sees this as part of a larger struggle for the community as she knows it,

It’s not about me trying to save my house. It’s about the numbers, about the energy. It’s about unity, about bringing people together. It’s about people just being able to be–and not [having to] defend themselves.

In addition to community members like Dawn and Roxanne, LSNA has other leaders who bring a strong sense of social justice along with institutional connections. For example, Father Mike is a Catholic priest who deliberately chose a parish in Logan Square because part of his mission included wanting to fight for affordable housing and social justice for low-income and minority citizens. As Father Mike told us, he takes a strong moral stand against displacement and encourages others in the community to take public action: “Because of my role as a leader and a religious leader in the community, I am very much a person of action.”

Finding Six: LSNA’s advocacy and organizing work on the issue of affordable housing is embedded in a multi-pronged approach that includes programs and services for renters and homeowners.

In 1994, LSNA and local banks lobbied state policy makers to modify the existing affordable homeownership program to make it accessible to people who could not buy an entire building. Forty-five families bought houses through this program. Approximately 50 more families bought houses through similar programs, and 16 have enrolled in a new plan to buy apartments in a cooperatively-owned building. The neighborhood banks continue to work together to hold housing fairs and provide seminars on homeownership issues. LSNA’s housing counselor estimates that, during the period of our research, hundreds of people have participated in counseling, workshops, and fairs about home equity conversions, default/foreclosures, pre-purchase concerns, and challenging tax assessments. In addition, LSNA has conducted outreach to hundreds of renters and has attained rental subsidies for 64 units by enrolling landlords in Chicago's Low Income Housing Trust Fund which provides rental subsidies to qualified landlords and tenants.

Recommendations for Building Community Capacity

Based upon our study of LSNA, Research for Action offers the following straightforward recommend-ations to community organizations and funders who would like to learn from the example of LSNA. While these recommendations may appear simple, they constitute a complex set of guidelines for building a community in which people both care about each other and are able to act on their own behalf.

|

Concluding Comments

As RFA completes our study of LSNA, we have several remaining questions about the future direction of the organization’s work. First, we wonder whether the organizational culture and values fostered by the current Executive Director are embedded deeply enough to outlast her tenure at the organization. Second, we wonder if LSNA’s growing involvement in the arena of citywide policy advocacy and organizing will alter its current approaches to relationship building, leadership development, and democratic participation on the neighborhood level. Finally, we wonder how LSNA will change as the Logan Square neighborhood itself continues to change.

These questions merely underscore the vitality and dynamism that LSNA embodies in its approach to building community capacity. LSNA’s successful approach to building community capacity is evidenced by its ability to integrate multiple voices, to draw on many skill-sets in the neighborhood, and to access many different types of resources. The organization’s program and strategies are deeply connected to the lives and realities of low- and moderate-income Logan Square residents, who describe profound changes in their self-esteem and self-confidence resulting from their involvement with LSNA. Finally, LSNA is composed of individuals who care about each other and who respond thoughtfully to shifting pressures and opportunities in the external environment.

Logan Square Neighborhood Association (LSNA), one of the grantees under the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation's Building Community Capacity program, is a forty-year community organization with a long history of mobilizing neighborhood residents to maintain and improve the quality of community life and to bring additional resources and services into the Logan Square neighborhood. Since May 1999, Research for Action (RFA), an independent Philadelphia-based nonprofit, and LSNA have been working together to document LSNA’s approach, activities, and the results of LSNA's organizing through qualitative, collaborative research. The focus of this study is on LSNA’s work since 1989 when its current director, Nancy Aardema, took over, with an emphasis on the years 1999-2002, when Research for Action conducted its research. This report documents LSNA’s approach and achievements in linking community organizing to the building of community capacity, tracing the similarities and differences in LSNA's methods, strategies, and successes in two different issue areas—education and housing.

Currently, LSNA has an annual budget of over one million dollars and an office-based staff of eighteen. Logan Square is a mixed income community with a large low-income Latino population. LSNA defines itself as an inclusive community-based organization with a commitment to organizing low- and moderate-income neighborhood residents. RFA's analysis shows that LSNA prioritizes the needs of these residents, many of them first or second-generation immigrants from Latin America. At the same time, the organization has an inclusive definition of "the community," and the membership includes a wide range of individuals and organizations: principals and parents; Latinos, Anglos, and African Americans; English and Spanish speakers; landlords and tenants; as well as churches, block clubs, social service agencies, and several community banks.

Like other initiatives committed to building capacity in low-income communities, LSNA has the goal of increasing the community's "ability to mobilize and use the resources of its members, along with outside resources, to foster individual growth and community development" (MacArthur, 1999). LSNA's approach is based on mobilizing and empowering community residents who have previously been excluded from positions of power. We believe that LSNA's approach has the potential to provide valuable lessons for funders and community organizers about relationships between the development and exercise of individuals’ capacities, on one hand, and achieving outcomes which benefit an entire community, on the other hand. LSNA sees a direct link between the building of civic engagement and leadership among the poorest residents of Logan Square and the community’s ability to develop programs and obtain resources which will support economic revitalization.

LSNA's work is guided by its Holistic Plan. This is essentially a detailed and continually evolving mission statement, which includes a series of objectives with which to assess its effectiveness each year. The Holistic Plan sets goals for key areas of action, such as improving local public schools, developing youth leadership, enhancing neighborhood safety, maintaining affordable housing, and revitalizing the local economy.

LSNA's executive director of thirteen years, Nancy Aardema, strongly believes that the organization is successful because it bases its work on building relationships of personal trust among individuals and organizations in order to act on community goals. During the past thirteen years, the organization has looked hard for ways to nurture diverse new social relationships within the Logan Square neighborhood. According to Aardema, LSNA draws on these relationships in developing a strong base of leaders from the neighborhood who can speak for the community and work effectively for social change.

LSNA's focus on relationship building makes it an especially appropriate site for exploring how low-income communities build their own capacity, an issue in which the John D. and Catherine C. MacArthur Foundation, other foundations, and policy makers on the federal, state, and city levels, as well as private businesses and scholars, are increasingly interested. Community capacity can undoubtedly be enhanced through external policies and resources, such as a regional transportation policy, tax policies that support urban business development, and subsidies for low-income housing. However, as necessary as these may be, they are not sufficient for creating healthy urban communities. Individuals and institutions in neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty also need to be able to work together to secure and utilize resources. This priority is reflected in the goal of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation: "The Foundation is committed to building the capacity of communities and helping them gain the ability to solve their own problems" (www.macfound.org).

RFA's research suggests that the creation of trust among community residents, between residents and institutions, and among community institutions has been key to LSNA’s successes in identifying and solving problems in Logan Square. RFA has been able to observe the ways in which LSNA's approach to relationship building intersects with issues of changing power and policy in the arenas of education and housing. Because LSNA’s work in schools and in housing are in different phases of an organizing campaign, we have also had the opportunity to observe different phases of the relationship building work.

LSNA's current work in schools demonstrates its approach to relationship building in a context in which it has already developed substantial power through a sustained organizing campaign. In observing LSNA's work with schools, we saw stable, active communities of parents and teachers that grew out of ten years of leadership development and community-initiated programming in the schools. LSNA's schools show consistent gains in test scores. These gains compare favorably with citywide gains, even though public school students in Logan Square are among the poorest in the city and are among the least likely to speak English.

LSNA's school/community partnerships, which many observers describe as an important contributor to school improvement in the neighborhood, are based on relationships of mutual respect that began developing over ten years ago as the community mounted a sustained and successful campaign against overcrowding. The success of this campaign stemmed from mobilizing the community, collaborating with principals and teachers in local schools, and developing relationships with public officials in order to hold them accountable to community needs. The successful school/community partnerships that now exist in Logan Square are based on the power of LSNA as a community organization.

LSNA's successful involvement with local schools developed, in part, because LSNA was able to take advantage of statewide legislation passed in 1988, which provided substantial power to parents and community members through the creation of elected Local School Councils (LSCs). LSNA was very active in recruiting and campaigning for the election of LSNA parents and other community residents to the LSCs. The power which LSNA gained from this organizing effort underlies its current success in implementing school-based programs.

In contrast to observing a set of school-based relationships that are the outcomes of a sustained organizing campaign, our observations of LSNA's housing work shows relationship building underway as it is central to the process of developing a campaign. As part of this campaign, we saw the slow process of relationship building among organizers and community members as well as the evolution of strategies for developing the community's power and holding public officials accountable to the interests of low- and moderate-income people. As this campaign evolves, it draws together people whose concerns range from very localized, block-level issues, to neighborhood-wide, and citywide issues. In its struggles at all these levels, LSNA is working to develop both relationships and accountability among elected officials, administrators in city government, and private development and financial interests.

In earlier phases of its housing work, LSNA was able to use legislative and judicial tools such as the Community Reinvestment Act and the Chicago Housing Court as levers for developing community power to address the needs of renters and families interested in becoming homeowners. Currently, as one part of the affordable housing campaign, LSNA is working to change citywide policy to slow down private housing development and maintain affordable housing units. In this campaign, LSNA is faced with the challenges of creating strong relationships within the neighborhood at the same time that it must counter citywide political and economic forces pushing many low- and middle-income residents out of Logan Square. From the perspective of members and leaders within the LSNA, the hard work they have done creating social ties and responsive institutions locally can easily be undone by economic and political forces originating at the city or state levels.

The issue of residential displacement of low- and moderate-income community members frames a new set of issues for those who are interested in building the capacity of urban communities. Even if capacity is developed around one set of institutions, for example, the capacity of the type that we will discuss in our chapter on schools in Logan Square, low- and moderate-income communities always face the potential of destabilization and/or disinvestment by business interests, developers, and their political allies. The threat of displacement in Logan Square helps us realize that although low- and moderate-income urban residents often need to develop new forms of social trust, they may already have, in addition, existing bonds that are threatened by forces from outside their communities. Countering these threats requires not only trust and skill, but also the development of power and public accountability.

As a neighborhood priest in Logan Square told us in discussing gentrification,

When the community begins to change, it is not just the houses. Suddenly we need more green space, more play space. Each time they go and tear something down, they say drug dealers lived there. There’s a feeling that now we deserve a park more than [someone] deserves a home. When the neighborhood begins to change, then the meaning of the neighborhood begins to change. (Father Mike, Catholic priest and housing activist)

A neighborhood housing leader, Roxanne Tyler,[1]also vividly described the social ruptures that occur during the process of gentrification. According to Roxanne,

Wherever you [once] lived, you had people and friends and support and [now] you have to move out to the suburbs, you might as well move to another country because you’re that far away.

Even when lower-income neighborhood residents may benefit from increasing property values, according to Roxanne, they are often critical of the lack of respect for the existing community among affluent newcomers.

One [condo owner] said to me in a meeting, “just think of all the money you’re going to make.” And I just looked at him and said, "You know I don’t want to make any money. I just want to live. I just want to live with my kids in my house… I think you have a right to profit, but when you come into my neighborhood, you’re supposed to respect me, and you don’t respect me when you come in here doing what you’re doing. First and foremost, it’s people like us who have stabilized this community so you felt safe enough to come in.

Until recently, discussions of urban poverty have largely focused on the need to bring additional resources into urban neighborhoods. However, as some American cities attract new investment, new jobs, and younger, more affluent residents, community capacity also becomes an issue of community identity and distribution of the power to allocate and access resources as well as the existence of material resources themselves. LSNA draws on a rich history of community organizing as it faces the challenge of maintaining a diverse, multi-income community in the face of new wealth coming into the neighborhood. While the threat of displacement makes the rupture of existing social relationships particularly vivid in Logan Square, LSNA's approach provides more general lessons about how low- and moderate-income residents can go about building and maintaining a vital urban community.

To a large extent, capacity building efforts to date in low-income communities nationwide have concentrated on Community Development Corporations (CDCs) and Comprehensive Community Initiatives (CCIs), with organizations like the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) and the Enterprise Foundation acting as funding intermediaries (Keating and Krumholtz, 1999). CDCs (neighborhood-based, non-profit business ventures) and especially CCIs (long-term efforts to coordinate planning and funding among a wide range of community organizations and agencies in low-income neighborhoods) require robust community leadership, as well as technical expertise and access to funding. However, CDCs and CCIs tend to prioritize the development of technical expertise and the formal involvement of institutional leaders, rather than mobilizing low-income community residents to identify and address their own needs (Hess, 1999; Keating and Krumholtz, 1999; Stoeker, 1999).

In contrast to CDCs and CCIs, grassroots community organizers base their work on the premise that poor and working class people can, and must, mobilize and build power to address their own needs and concerns (Alinsky, 1971; Delgado, 1986). In addition, contemporary community organizing often incorporates insights derived from feminist thought, including the importance of focusing on interpersonal relationships and dynamics and the connections between personal and political issues (Gittell et al., 2001; O'Donnell and Schumer, 1996).

Styles of community organizing vary across organizations and individuals, but current community organizing groups share a commitment to building leadership among their members, mobilizing their constituencies, and developing mutually beneficial relationships with elected officials and others in more traditional positions of power (Gold, Simon and Blanc, 2002). In addition, grassroots community organizations traditionally work hard with neighborhood leaders to identify winnable issues, build strategic alliances, and maintain long-term campaigns for attaining the community's strategic goals. The examples of LSNA and other community-based groups around the country suggest that approaches to leadership and community mobilization that characterize grassroots organizing can be useful to organizations that also have characteristics of CDCs and CCIs, even though there is some debate about whether the organizational structures and philosophies of community organizing and community development are compatible (e.g., Hess 1999; Stoecker 1999).

This study of the work of LSNA provides an opportunity to observe the processes of community capacity building within a specific context. Our aim is to represent and give voice to the attempts of one experienced community-based organization to mediate larger economic and political forces and play a significant role in shaping the future of its neighborhood. In the report, we have also tried to capture the complexity of the work of LSNA to make clear that none of this work happens without considerable difficulty involving challenges from external obstacles and the need to deal with internal differences in point of view.

RFA's research about building community capacity in Logan Square, conducted between May 1999 and January 2002, documents the ways that LSNA's organizational structure brings together numerous groups and interests within the Logan Square neighborhood. In addition, case studies of LSNA's work with schools and housing demonstrate how the organization's relational approach to community organizing plays out in two different issue areas. The two areas of focused research, schools and housing, were chosen in conjunction with LSNA organizers who were interested in documenting both LSNA's extensive impact on school improvement and the nascent campaign to maintain affordable housing in the community. In this work, we have looked carefully at the structures and processes that LSNA uses to strengthen the Logan Square community. In addition, we look at the ways that the Logan Square community and LSNA interact with broader social, economic, and political forces that impact the organization's ability to build internal community capacity.

RFA's research about LSNA has been guided by the following questions, developed in conjunction with LSNA staff members:

|

LSNA's noteworthy accomplishments in the realm of building community capacity include:

|

In order to understand how LSNA accomplishes these capacity-building activities, we look at LSNA's activities through four different lenses: relationship building, leadership development, democratic participation, and building power and changing policy. LSNA’s approach to dealing with community issues is indeed multi-dimensional. The four lenses provide a framework for describing and analyzing LSNA's philosophy and practice without prioritizing one dimension of its approach. We believe that these lenses can be used to look at both aspects of LSNA’s work that relate to the internal dynamics of the Logan Square neighborhood and those which relate to broader social, economic and political forces and institutions.

This framework allows us to see that a certain aspect of LSNA's approach may be particularly important to the organization's work on a given issue at a particular moment in time. Additionally, the framework helps us to examine LSNA as a whole. Looking through the various lenses permits us to view and understand that LSNA’s strength grows out of its ability to simultaneously build relationships, develop leaders, encourage democratic participation, and build power to change policies in ways that will support a strong, diverse, urban neighborhood.

As a conceptual framework, we see these four lenses corresponding well with the thinking of the Aspen Institute. In a 1996 paper entitled “Measuring Community Capacity Building,” the Institute identified eight outcomes. These include: growing diverse, inclusive citizenship participation; expanding a leadership base; strengthening individual skills; developing a widely shared vision; forming a strategic community agenda (including a plan); evidencing consistent, tangible progress toward goals; producing more effective community organizations and institutions; and better resource utilization by the community. We see evidence of all eight of these outcomes when we look at LSNA’s work over the course of our fieldwork through the four lenses we have defined.

Looking through the Lens of Relationship Building

Using the lens of relationship building, we see that LSNA has been able to develop a campaign for affordable housing based on relationships and common interests among low- and moderate-income renters, homeowners, and public housing residents, as well as community banks in Logan Square, even though this campaign challenges the interests of powerful real estate developers and some middle class and more affluent newcomers to the neighborhood.

The creation of new relationships is fundamental to all processes of community change. Relationships create new forms of friendship and support within the neighborhood. Relationship building, sometimes referred to as the creation of "social capital," leads to networks of mutual obligation and trust, both interpersonal and inter-group, relationships which can be called on to leverage resources for addressing community concerns.

LSNA builds relationships gradually and deliberately. One key component of relationship building takes place as LSNA organizers meet individually with community members in their homes, schools, churches, and the LSNA offices. At these meetings, organizers and community members discuss their lives, their community and what is happening to and around them. These “one-on-ones” are key to developing new community leaders. In LSNA's Parent Mentor program, parents also work together in groups to identify their concerns, goals, and dreams, as well as the strengths they bring to their families, schools, and community. Whether relationship building begins with individual conversations or in group discussions, it takes time to learn about individuals’ goals for both personal growth and neighborhood improvement.

Like many other community organizing groups, LSNA brings people together who might not otherwise associate with each other, either because of cultural and language barriers (e.g., Latinos and African Americans) or because of their different roles and positions, such as teacher and parents or renters and homeowners. Given LSNA’s goals of functioning democratically and representing a diverse community, relationship building across differences in race, ethnicity, income, and status is essential.

Relationship building also extends outside of the neighborhood and involves developing connections with funding sources, elected officials, and community groups in other neighborhoods. As we show in the following chapters, in its work with schools, LSNA has developed an extensive network of relationships with school administrators, politicians, and foundations inside and outside of Chicago. In its current housing campaign, LSNA is developing a new set of relationships with public officials and policy makers. Also of great significance in the housing campaign is LSNA’s building of alliances with other grassroots community organizations interested in working collaboratively for affordable housing in many parts of the city.

Looking through the Lens of Leadership Development

LSNA’s leadership is diverse and represents the broad spectrum of community residents, including both lower-income, often Spanish-speaking individuals and higher-income professionals (bankers, lawyers, teachers, etc.). In recent years, the proportion of lower-income leaders has increased. With the guidance of LSNA’s executive director, Nancy Aardema, the organization works to maintain a culture of mutual respect and shared authority among people with different education and employment histories, priorities, and beliefs about their right and capacity to exert influence.

Different aspects of LSNA’s work may involve different degrees of interaction and collaboration among individuals of different ethnicity and income-level or social class. The groups of LSNA members and leaders working on targeted projects, such as the Parent Mentor program or Community Centers in schools, may be relatively homogeneous, whereas the governance of LSNA and its subcommittees is likely to be more multi-class. It is in these situations that Nancy exercises her interpersonal skills—encouraging the participation of those with less experience in the public forums and modeling an attitude of equal respect for all—to help maintain a truly democratic environment and process.

Much of what leadership means in LSNA reflects the literature on community organizing, including the tradition of Alinsky-style organizing, with its historical roots in Chicago[2]and its emphasis on the idea that poor and working class people can, and must, provide leadership to a grassroots movement to address the needs and concerns of their own communities. Leadership in LSNA also incorporates contemporary thought on collaborative leadership which stresses the value of broadly-based and distributed leadership within an organization, rather than the value of a smaller, stronger leadership group.[3]

In our research protocols, we asked LSNA members directly what the term “leadership” meant to them and how one becomes a leader in LSNA. Community members and LSNA organizers describe a gradual process of leadership development that helps people to clarify their own beliefs and become comfortable with expressing their views in ways that link their own experiences to those of the people they represent. LSNA members said that leadership development encourages individuals, especially women, to challenge traditional power relationships in their own lives. Leadership development helps community residents to sharpen their skills for civic engagement through opportunities to speak publicly, lead meetings, interview public officials, and negotiate with those in positions of power. While leadership development has to do with enhancing the scope and nature of the work performed, it also has to do with the way an individual becomes accountable in public to others. As leaders develop a stronger sense of connection with their community, their willingness to be publicly accountable begins to unfold.

One important way that grassroots leaders develop is through becoming involved in the organization from the bottom up, in arenas like the Parent Mentor program, which pays parents small stipends to participate in leadership training and work in Logan Square classrooms. This program, which is designed to attract community members, places them in a program which trains them to become engaged in a public institution, and develops a large base of support composed primarily of women who would not otherwise be active in their community. In the area of housing, community members have been recruited to become leaders through their involvement with the Low Income Housing Trust Fund, a program which provides rental subsidies to low-income renters. LSNA's affordable rent committee actively mobilized community residents to advocate for the maintenance and expansion of this Fund.

Looking through the Lens of Democratic Participation

LSNA embodies more than one avenue for democratic participation. LSNA's power to change policy depends on its ability to mobilize the community to apply pressure on elected officials and others in power, whether through lobbying efforts or through more activist forms of organization, such as large-scale demonstrations. In addition, LSNA also encourages community members to participate in internal democratic processes which bring community members together to make shared decisions about community needs, strategies, and priorities. Democratic participation in the annual process of publicly evaluating and revising LSNA’s Holistic Plan is key to debating and articulating a shared vision for Logan Square.

Logan Square is far from a unitary community, and LSNA includes many of the neighborhood’s different social, economic, ethnic, national, and political groupings. While many people move in and out of the organization, there is a core who strongly identify with LSNA and with the Logan Square neighborhood and who provide stability to LSNA. Through the relationships developed and through the process of discussion and dialogue, LSNA provides a vehicle for identifying shared interests and creating a sense of community, thus bringing together people who might otherwise see themselves as having little in common. The process in LSNA can be characterized as highly interpersonal, relationship-oriented, trust-based, and situated within a democratic structure.

It is important to underscore that many of LSNA’s members and leaders do not have prior experience with holding positions of power or being able to control the conditions of their lives. For these individuals, democratic participation is an expression of their emerging sense of political and social entitlement. Our final lens, building power and influencing policies, grows out of this sense of entitlement, made visible in democratic participation.

Looking through the Lens of Building Power and Changing Policy

People who have been excluded from power can gain power by participating in public dialogue, developing shared visions and strategies, community mobilization, and gaining recognition and response from public and private officials. Methods of organizing for power include operating through formal political channels (e.g., petitions, meetings with elected and city officials) as well as grassroots actions that galvanize people’s outrage and sense of injustice in public protest. LSNA's sustained campaigns over time, its clear organizational identity, and its success in gaining political recognition for its agendas in education and affordable housing are all evidence of the community power that LSNA is using to make Logan Square schools into responsive, high quality institutions and to ensure the future of Logan Square as a stable, economically diverse neighborhood.

While community power is crucial to LSNA's work in the areas of both housing and schools, the role community power plays in these two arenas is somewhat different. In its work with schools, community power is critical because it allows LSNA to enter into school/community partnerships, based on relationships of trust and mutual respect. In contrast, in its work to maintain affordable housing, community power is critical to LSNA in order to challenge the interests of established power and money that currently dominate the real estate market, both in Logan Square and more broadly in Chicago.

In part this contrast is due to the different impacts of policies that shape schools and housing in Chicago. In the area of education, LSNA was able to take advantage of IL85-1418, a 1988 state law which decentralized the Chicago school system, giving substantial power to Local School Councils (LSCs), a majority of whose members are elected parent representatives. The 1988 education law, which was enacted in response to grassroots organizing by a broad citywide coalition of community organizations, parent and education policy groups, and corporations, establishes the power of LSC to hire and fire principals and make key budget decisions. The implementation of this legislation, which was supported by a simultaneous interest on the part of foundations, provided an important opening to create partnerships with neighborhood schools, develop schools as centers of community, and build new community leadership for LSNA’s work in other issue areas. As we show in our case study of LSNA’s work with schools, LSNA’s success in this work is based on its power to mobilize community members, the specific policy context affecting Chicago schools has also provided avenues for LSNA to develop and maintain its power as a community group.

In contrast, the area of affordable housing offers few

existing policy levers for community activism. An important focus of LSNA's

current housing work involves mobilizing its local constituency to develop a

citywide coalition with enough power to counterbalance market-driven

development policies. In the current environment, local aldermen hold enormous

power to support or deny zoning changes that builders need to establish new

housing developments in their wards; the aldermen are extremely responsive to

campaign contributions and political pressures applied by powerful real estate

developers. The lack of a robust public policy supporting affordable housing

in Chicago is particularly problematic for neighborhoods like Logan Square,

where many low- and moderate-income community members have already been forced

to leave by increases in housing costs. As we show in our case study of

housing, LSNA's housing work is proceeding on many fronts, but a major thrust

of the affordable housing campaign is building the power of low- and

moderate-income communities to challenge existing housing policies.

LSNA's goals are to build the strength of its community and to gain and maintain resources and policy changes that will support the diverse families of Logan Square. Some political theorists (e.g., Gaventa 1980; Lukes 1974) argue that low-income or minority communities that are shut out of traditional decision-making processes need opportunities to envision their own political agendas and often must mobilize outside of the traditional political system. In our observations of LSNA, we have seen a well- developed partnership with schools and an evolving campaign for affordable housing. In both arenas, LSNA's ability to gain attention for community issues and get a seat at the table is the result of its capacity to develop relationships and leaders, to identify community needs through broad participation in the organization, and to develop strategic plans for constructive, collective action.

Chapter II provides an historic overview of LSNA and an analysis of its current structure and overall processes. Chapters III and IV are analytic case studies which look at LSNA’s work in the areas of reforming schools and organizing for affordable housing through the lenses of relationship building, leadership development, democratic participation, and building power and changing policy. Chapter V, the concluding chapter, presents an overall analysis of how these processes are realized differently in LSNA's work with schools and housing. We also consider what foundations and other community organizations can learn from LSNA's approach to community change. In the appendices, we present detailed information about the project’s research methods and activities.

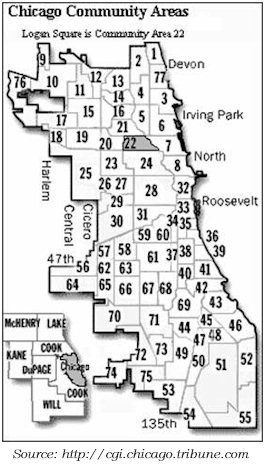

Located

on the northwest side of Chicago, Logan Square, Chicago Community Area 22, is a

neighborhood of roughly 83,000 inhabitants. Logan Square’s political boundaries

include portions of the 26th, 31st,

35th,

and with recent redistricting, 1st Wards. According

to 2000 census data, 66% of the population is Latino, 27% is non-Latino whites,

5% is non-Latino African Americans, 1.5 % Asian and Pacific Islander, and .19%

Native American (Census 2000 at www.suntimes.com). The community area includes

a wide range of housing stock and economic groups. Household income census

data available at the time of this writing shows that in 2000 Logan Square, the

median household income was $36,245. Seventeen percent of the total population

received public assistance in the form of Aid for Dependent Children, Medicaid,

or other forms of assistance.

Located

on the northwest side of Chicago, Logan Square, Chicago Community Area 22, is a

neighborhood of roughly 83,000 inhabitants. Logan Square’s political boundaries

include portions of the 26th, 31st,

35th,

and with recent redistricting, 1st Wards. According

to 2000 census data, 66% of the population is Latino, 27% is non-Latino whites,

5% is non-Latino African Americans, 1.5 % Asian and Pacific Islander, and .19%

Native American (Census 2000 at www.suntimes.com). The community area includes

a wide range of housing stock and economic groups. Household income census

data available at the time of this writing shows that in 2000 Logan Square, the

median household income was $36,245. Seventeen percent of the total population

received public assistance in the form of Aid for Dependent Children, Medicaid,

or other forms of assistance.

From outward appearances, Chicago looks to non-residents like a thriving multicultural city but it is in fact among the most segregated of American cities and can be mapped out as a series of neighborhood pockets divided by race and social class. Logan Square is one of the very few Chicago neighborhoods that is both multi-racial and multi-class and has been for decades. LSNA has been successful in bringing into its membership Anglos, Latinos, and African Americans, young people as well as seniors. LSNA's membership includes some people who live in the historic greystone mansions along Logan Boulevard and others who live in Lathrop Homes, the public housing units just across the river in the adjacent neighborhood of Lakeview. Members of the Logan Square Neighborhood Association are wrestling with how to find a way to preserve the economic and multicultural diversity that is still a part of their neighborhood even as the surge of townhouse construction and condo conversion continues to roll through their community.

Logan Square Neighborhood Association is a well-established community organization that was started in the early 1960s by a group of local churches, businesses, and homeowners to address neighborhood concerns arising from rapid suburbanization and deindustrialization in the Chicago metropolitan area. Around the time of LSNA's formation, longtime residents of Logan Square, primarily working-class families of European descent, were leaving Logan Square and new residents were moving into the area, many of them Cuban and Puerto Rican families coming from poorer neighborhoods. Although residents organized in the 1960s to fight community deterioration when long-term residents and businesses began to leave, incoming Latino families moving into Logan Square in the 1970s perceived “living in Logan Square...as a measure of social prosperity and achievement” (Padilla, 1993:134).

Padilla's valuable study of Puerto Ricans in Logan Square portrays Logan Square as a place of "second settlement" that attracted many upwardly mobile Latinos who viewed the neighborhood as a “serene and tranquil neighborhood, a place with safe streets and good public schools” during the 1970s. To meet the growing demand of Latinos for food and other specialty items, Latino businessmen developed the commercial streets into a Latino-dominated shopping area that included Puerto Rican, Mexican American, and Cuban food stores, restaurants, and jewelry stores. In addition, Latino professionals established other small businesses such as travel agencies, law firms, realtors, and accountants to meet the special needs of the immigrant community. Beginning in the 1980s, several non-profit organizations, including Aspira, the Boys and Girls Club, and Hispanic Housing, also focused on the educational and housing needs of Latinos in Logan Square.

In addition to several active commercial strips and community banks, the attractive housing stock, good public transportation, and geographical accessibility from the neighborhood to downtown Chicago and O’Hare airport have continued to attract middle-class professionals of all races since the 1970s. Thus, the neighborhood did not face the degree of financial disinvestments and racial segregation common to many low-income Latino and African American neighborhoods.

Since its inception in 1962, Logan Square Neighborhood Association has worked to maintain the financial stability of the neighborhood and has grappled with how to position itself relative to the differing interests of working-class and middle-class constituencies within the neighborhood's geographic boundaries. LSNA's membership has consistently included community residents who represent the interests of a range of economic and ethnic groups.

Source: LSNA Holistic Plan-2002 |

LSNA and Chicago Public Schools

In 1988, Illinois enacted legislation that mandated local community control of Chicago public schools. It is possible to analyze the 1988 reform as meeting a wide variety of agendas. For business interests, the reform was seen as a means of fixing schools, a necessity for attracting investment, supporting the development of up-scale neighborhoods, and promoting Chicago as a global city. The school reformers saw decentralization of school control as a vital strategy to democratize control of schools and promote innovation. Some social justice activists saw it as an opportunity for grassroots organizing and grassroots community power.

Shipps (1997) argues that the decentralization plan was primarily a business initiative to reform the schools in the interest of larger development plans. Business interests promoted a decentralized management style popular with major corporations to increase innovation and efficiency by reducing bureaucracy. On the other hand, Designs for Change, one of the architects of the plan, saw the reform as a grassroots strategy to democratize schools and give more power to parents and communities. Prior to 1988, a series of teachers’ strikes led to widespread public protests and grassroots mobilization for improvements in public education. Mayor Harold Washington initiated an Education Summit (actually taking place after his death), which brought the school reformers together with the business interests to fashion the outlines of the 1988 reform.

For Washington, the school reform fit with his plan for economic development that focused on keeping industries in the communities and promoting development in neighborhoods as well as downtown. It also fit with the politics of the Washington administration, which was rooted in grassroots community support and an effort to break from Democratic machine politics. Local school organizing was a piece of that strategy.