| COMM-ORG Papers 2003 |

Blanc et al.: From the Ground Up |

| Preface | Summary | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Appendices | Cited Works and Notes | Acknowledgements and About Authors |

I arrive with the LSNA education organizer to interview the outreach team about the new community survey they are doing for Monroe School Community Learning Center. Six Latinas are sitting in the school's teachers’ lounge. The organizer told me that the mothers had taken it upon themselves to move into the teachers’ lounge, which she perceived as their sense of ownership of the school. When I arrive, each woman has an orange folder in front of her, and they’re looking intently at maps that are blocked off with colored markers to show the different parts of the neighborhood. They’re engaged in animated discussion about who should go where.

We start the focus group, and they agree that everyone on the outreach committee participated in the Community Learning Center last year. Margarita[9] works in the Center. Marisol is on the student council for the Center. Everyone has taken GED or English classes. Someone else jokes, “This is the organization of the Monroe School." Three of the women were parent mentors. Latitia helped recruit parents to run in the most recent Local School Council election and is also the president of the bilingual committee. (RFA researcher's fieldnotes, fall 2000)

As this vignette suggests, parents in Logan Square demonstrate a sense of engagement and ownership unusual in urban schools. In this chapter, we begin with an overview of LSNA's approach to school/community collaboration, provide an analysis of how this collaboration developed, and then discuss LSNA's work in schools through the four lenses of relationship building, leadership development, democratic participation and building powerand changing policy.

LSNA's close collaboration with local schools began in the early 1990s when LSNA’s Education Committee spearheaded a community effort to end school overcrowding. For years, before LSNA's involvement, individual schools in Logan Square had been negotiating with the Chicago Board of Education to end severe overcrowding. During the early 1990s, LSNA played a crucial role in bringing together schools from across the neighborhood to address this common problem. Local School Councils and principals signed on to this campaign, joining the LSNA Education Committee, and schools became members of LSNA. With this campaign, LSNA shifted its strategy from organizing only parents to forming a coalition that also included school staff. Over several years, the campaign resulted in five new annexes and two new middle schools. Just as importantly, the campaign both demonstrated LSNA's power as a community organization and built a foundation of mutual trust and respect among the principals, teachers, parent leaders, and LSNA staff who had been involved in the campaign and witnessed the results. The campaign also established a basic vision for LSNA’s education work.

Joanna Brown, who organized the campaign for the annexes, notes:

By the end of the overcrowding campaign, the entire coalition—principals, parents, and teachers—were speaking with one voice on the need, not only to build the annexes, but to use them in the evening as community centers to serve neighborhood needs. This was a fairly radical demand, as virtually all Chicago public schools up to that point closed their doors by 4 p.m. The coalition also began to talk about how to involve parents more fully in the schools.

Since then, LSNA has deepened and built on this collaboration as it has worked to make the schools centers of community. Two principals, Sally Acker of Funston School and James Menconi of Monroe School, worked with parent leaders and others to write LSNA’s first Holistic Plan in 1994, with its three education resolutions: 1) make schools centers of community life through Community Learning Centers, 2) develop school/community partnerships with parents as leaders, and 3) develop the Parent Teacher Mentor Program to help parents develop their skills, assist teachers, and build strong relationships in the community.

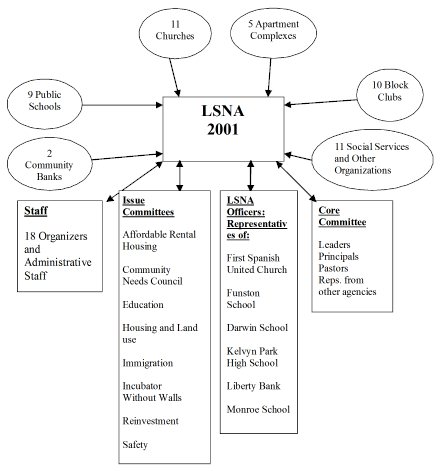

| LSNA Member Organizations and Committees |

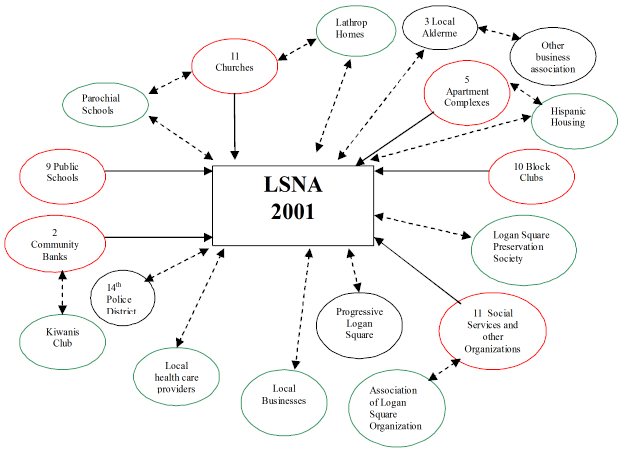

| LSNA's Web of Neighborhood Relations |

Today, LSNA runs Community Learning Centers in six schools, with 1,400 families participating in classes weekly. LSNA runs parent mentor programs in seven schools, and more than 900 parents (mostly mothers) have graduated from the program since it began in 1995. Both of these programs are run in a complex partnership with the schools. These programs involve shared financial and administrative management and shared space, all of which are negotiated school by school. In Joanna's words, "These collaborations are built on trust, but, fraught as they are with potential conflicts, require constant care and feeding." The collaborations are also supported by the fact that LSNA is the lead fundraiser, putting an average of $100,000 to $125,000 into each school yearly, mostly in the form of stipends and salaries to parents and other neighborhood residents working in the schools.

With these programs, LSNA has increased the quality of programming and services available to children and families in Logan Square. These programs impact the educational experience and achievement of Logan Square children and bring significant financial resources into the schools and the neighborhood. The partnership between LSNA and the schools has extended broadly into partnerships between schools and the community, evidenced by collaborations which range from local banks' homeownership programs for teachers in Logan Square schools to intergenerational projects between Logan Square middle schools and nearby senior centers.

In 2000, LSNA was selected from 187 Chicago-area organizations as winner of the Chicago Community Trust’s Award of Excellence for Outstanding Community Service. LSNA’s vision of its accomplishments was articulated in its successful nomination proposal:

People in Logan Square—parents, principals, teachers, students, neighbors—think differently about education today than they did a decade ago. Parents are welcome in the schools; they are seen as essential to education, not only in their homes, but also in the classrooms. Schools no longer are seen as isolated and gated institutions but as centers of their mini-communities. The chasm between school and home is bridged, as children see their mother and her friends working and studying in the school. The community is seen as a resource for education. Logan Square Neighborhood Association has been an essential and welcomed partner in forging this collaborative.

Since 1996, all LSNA elementary schools have experienced significant increases in student achievement, even while the demographics have remained constant. For example, from 1996 to 2001, the percentage of students at one school reading at or above the national norm on the yearly Iowa Test of Basic Skills rose from 17.5% to 29.3%. In math, the percentage rose from 19.5% to 31.4%. Even more telling are the dramatic shifts in student scores from the lowest to second lowest quartiles. This is noteworthy because parent mentors usually work with the students who are most behind. Other LSNA schools showed similar increases over the same time period. These increases in test scores compare favorably with citywide averages, especially taking into account the relatively higher rate of poverty and higher numbers of non-English speaking students in Logan Square schools.[10]

Principal interviews and parent interviews and focus groups attribute a significant portion of these gains to the regular presence of parents in classrooms through LSNA's Parent Teacher Mentor Program. Teachers, parents, and principals articulate the belief that parent mentors play an important role in improving the climate for learning in classrooms by giving help to individuals and small groups, keeping students on task, and developing close relationships with students. One major impact of the Parent Teacher Mentor Program is that it lowers the student/teacher ratio and gives individual help to some of the children most in need. The following comments, which are typical of those that we heard from teachers and parents, illustrate why the parent mentor program appears to be impacting student achievement, especially for those at the lowest achievement levels.

My parent mentor takes my kids who would be the lowest readers out. Works with them one-on-one (teacher)

We all can use an extra set of hands… [Now] these kids get the help they need (teacher)

The teachers notice how well the students are making progress because they're interested, and I keep the students' interest going (parent).

LSNA has been very active in [making schools] a center of community, not just a place where kids and a group of professionals descend…It is not just a place where you can depend on kids to receive an education, but also the place where you participate in the governance and deciding what goes on there and building it up and helping it grow. (Logan Square minister, spring 2000)

When I came into the school for the first time, it was important for me to understand what was happening, but I was one of those people who were very timid. After three or four years, I got more involved. I don't understand it all yet, but I know the importance of getting involved. I'm new here, but I'm happy to be part of the Local School Council and president of one of the school committees. (Parent Leader, fall 2000)

Parents, teachers, principals, and community members helped to make education one of the major issues in LSNA's first Holistic Plan, which was written in 1995. Working for two years, these different constituencies built on relationships they had developed in the campaign against overcrowding and wrote three education resolutions, which focused on the interdependence of the schools and the community. In its first Holistic Plan,[11] LSNA resolved to:

|

This resolution included support for training for LSC members and a program developed by local banks and LSNA to help Logan Square teachers buy homes in the neighborhood.

Following the adoption of the first Holistic Plan, LSNA received foundation funding to pilot the first Parent Teacher Mentor Program. Local School Council members and other parents worked with LSNA to bring the Parent Teacher Mentor Program into their schools and then to keep their schools open after regular school hours for Community Learning Centers. In addition to working directly with parents, LSNA has continued to involve principals and teachers in LSNA activities such as quarterly principal meetings, the neighborhood-wide Education Committee, and the LSNA Core Committee.

LSNA’s recognition of the interconnections between school and community and the importance of school/community collaboration is well illustrated by its two largest programs. Partnering with the Funston School and a technical assistance consultant (Community Organizing for Family Issues), LSNA developed a program with far-reaching effects—the Parent Teacher Mentor Program, which pays parents a small stipend to attend leadership training and then participate in a minimum of 100 hours of training as they work with children in classrooms. As parent mentors, mothers (and occasionally fathers) increase their understanding of the current culture and expectations of the schools. They take on new roles such as tutoring, reading to children, or coordinating literacy programs. They also learn that the skills honed by “just” being a good parent translate into leadership skills in the larger community.

LSNA’s Community Learning Centers are another major example of school/community collaboration in Logan Square. LSNA and the schools had agreed that the new school annexes would be open for community activities. The first Community Learning Center was created by the first group of graduates from Funston's pilot Parent Teacher Mentor Program. The women developed a community survey and began knocking on doors to find out what the neighborhood wanted in a community center. They then advocated with citywide providers to get the desired programs. Since then, Funston's Community Learning Center and five others, which collectively serve over 1,400 children and adults a week, continue to be guided by the vision and energy of neighborhood residents.

Looking at LSNA’s work through the four lenses of relationship building, leadership development, democratic participation, and building power and changing policy helps us to understand how LSNA has been able to use and maintain community power to create strong, respectful partnerships between the schools and the community. Because LSNA parents, principals, and teachers are all members of a powerful community organization, the campaigns and programs they create are based on parent/professional relationships that are different from those traditionally found in urban schools.

This chapter begins with an examination of LSNA's education work through the lens of building power and changing policy. We begin with this lens for a particular reason. Fundamentally it is because LSNA had a well-developed approach in this area when RFA arrived in 1999 to begin field work. LSNA's power in the arena of education comes from its strength in sustaining campaigns over time and drawing political attention to its education agenda. LSNA's successful campaign to alleviate school overcrowding, which involved gaining political recognition and winning new buildings for neighborhood schools, is one illustration of its power. LSNA's power in the realm of education continues to build as LSNA leaders and members take active roles in their Local School Councils, create school-based programs that are controlled by the community, and successfully advocate for city, state, and national funding for these programs. Within the organization, LSNA's support for grassroots leaders and democratic structures help parents and community members articulate their concerns about schools to principals and teachers.

Second, the report examines LSNA’s education work through the lens of relationship building. LSNA has worked hard to successfully build relationships among parents, between parents and teachers, among principals, and between schools and other organizations in the neighborhood. In addition, LSNA plays a critical role by building relationships which connect Logan Square schools to funders and other organizations outside the neighborhood and city.

The chapter looks next at LSNA through the lens of leadership development. In this section, we discuss the leadership opportunities created by the education organizing work of LSNA and the ways in which LSNA identifies and trains parents and community members to take on leadership roles. We end by using the lens of democratic participation to explore democratic processes in LSNA’s education work, both in the schools and in the internal processes of LSNA.

Building Power and Changing Policy

Community power is critical to LSNA’s ability to enter into school/community collaborations as a partner, based on relationships of trust and mutual respect. Sustained campaigns and public recognition of LSNA’s education work are both evidence of LSNA's power as a community organization.

After years of meetings with the Board of Education, they finally bought the old Ames property for a new middle school. But that wasn't the end of it. One morning, we got a phone call from one of our leaders saying that the Board of Ed was closing a deal on the sale of the property to a private developer that afternoon. Immediately, the Education Committee and the parent mentors were on the phone to the parents who had been working on the campaign. Two hours later, hundreds of community people were picketing. Later that day, we found out that they had cancelled the deal. Finally, in 1997, after six years of organizing, ground was broken for the Ames Middle School. (Narrative told to RFA researcher by a group of LSNA leaders, May 1999)

LSNA's ability to sustain campaigns over time is one important measure of a strong community base, which contributes to effective school/community collaborations. LSNA's campaign against overcrowding began in the early 1990s and continued for over five years. During our fieldwork, RFA heard many stories of the abysmal conditions in Logan Square schools during those years: 45 children in a classroom; classes meeting in the nurse's office or on the stage and auditorium floor; art and music classes cancelled because the space was needed for regular classroom instruction. During the first phase of the campaign against overcrowding, parents from three elementary schools proved that they could work together to identify a mutually acceptable location for a new middle school.

The first victory spurred parents from five elementary schools to work with LSNA and push for additional space. Together, parents from these schools spent another year and a half preparing to appeal to the Board of Education. They developed a multi-step campaign that began with meeting individually with members of the Board of Education to educate them about the need for new schools. At these meetings, LSNA parents convinced each member of the Board of Education to commit him or herself to supporting new facilities for Logan Square schools. A later step of the campaign was to bring hundreds of Logan Square parents to a Board of Education meeting where the individual members of the Board of Education were asked to publicly affirm the commitments that they had previously made privately. The ability to develop strategies for sustained, multi-step campaigns is an essential element of building power for community groups.

A parent, LSC chair, and former president of LSNA explained how LSNA parents were able to win new buildings for their neighborhood:

There were many meetings with parents to prepare for going down to the Board of Education. What was funny was that no one would commit in a large group. But we went around and got individual commitments. We had many, many meetings. It was a year and a half of meetings. And then we finally all came together in one big room. You could feel the tension in the room. And once we started the meeting it was like, “Well, you know, so and so, you said that if so and so supported it, you will support it," and we would call on the names, “Well, are you here in support?” It was empowering because you finally beat this huge Board of Ed.

After the additions were completed, LSNA began another round of organizing, this time to win construction of the new Ames Middle School and then a role in the selection of its principal. In the words of community organizers, they "gained a seat at the table" for principal selection. Although LSCs have the right and the obligation to hire the principal for an existing school, the CEO of the Chicago Public Schools, Paul Vallas, had insisted on choosing the principal for the new middle school. To convince Vallas of the value of community input, parent mentors and LSC members from two of Ames feeder schools, Mozart and Funston, visited his office to share with him the important work that LSNA was doing in the Logan Square schools. A few days later, Paul Vallas came to Logan Square for a meeting about LSNA’s school-based Community Learning Centers.

According to LSNA's Executive Director,

If you don’t have power, you’re not going to have a meeting with Paul Vallas. We told him he needed to come to the neighborhood and get a sense of how parents, teachers, principals, and pastors were working together. He was trying to change the standards for the Chicago Public Schools then, and LSNA's president at the time told him, “We need you, but you also need us.” He needed the parents; he needed the principals; he needed the teachers. He got the point. At the end of the meeting, Vallas came and said, “We want to see your top education leaders.” That was when he said we could form the committee for the principal selection.

A committee made up of local principals and LSC members selected as principal a local bilingual education coordinator who had been a leader in the fight against overcrowding, had helped to organize the first Parent Mentor program, was at that time LSNA's vice president, and had expressed a strong commitment to making Ames "a community-centered school.” Vallas accepted the selection.

These examples show that LSNA has strong community leaders who can sustain campaigns over the time it takes to develop power and “gain a seat at the table.” The fact that LSNA was able to exert such an influence on Chicago Public Schools’ policy-makers won appreciation of LSNA’s power, and enabled LSNA to enter into school/community collaborations as a respected partner.

In the spring of 2000, LSNA's Education Committee, composed of parent representatives from each of its member schools, began to discuss an issue which they termed "respect for children." After years of classroom-based collaboration between parents and teachers, parent mentors began to act on their concern that too many Logan Square teachers were using negative, rather than positive, approaches to discipline. During the fall of 2000, parents on the Committee met individually with several principals. They also asked to meet as a group with the LSNA principals to discuss the issue, although they were nervous and cautious because they felt the issue was sensitive. As one of the Committee members explained,

We are trying to do something about the respect of teachers for children, and on both sides. We don't want to pick out certain teachers. We don't want to get into arguments. We simply want to say that this is a serious problem.

LSNA has received much public recognition for its education work from political leaders, funders, and the media. Evidence of LSNA's political recognition in the arena of education includes:

|

Other examples of public recognition during the period of this research include the Chicago Community Trust's 2001 James Brown Award for Outstanding Community Service to LSNA, extensive radio and television coverage of LSNA's Parent Teacher Mentor Program, and LSNA's hosting a site visit from a national consortium of education funders. Funding is also evidence of public respect for LSNA's ability to create school/community partnerships. LSNA's education organizing and school-based programs are funded through many sources, including: the John T. and Catherine D. John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; the Chicago Board of Education; the Chicago Department of Human Services; the Chicago Annenberg Challenge (a major school reform initiative that supported LSNA as an external partner to five Logan Square schools); the Polk Brothers Foundation and several other smaller Chicago foundations; the Illinois State Board of Education; the Illinois Department of Commerce and Community Affairs; the Illinois Community College Board; and the U.S. Department of Education’s 21st Century and Title VII career ladder grant. These multiple sources of funding enhance LSNA’s power within school/community collaborations.

LSNA’s sustained campaigns, successful programs, and the public recognition granted its work in schools have all contributed to building power for LSNA in the sphere of education. This power has made possible LSNA’s collaborative partnerships with the schools and motivated school personnel to become active members of LSNA and the Logan Square community.

LSNA serves its goal of linking schools and communities by developing webs of relationships among parents, between parents and school staff, among schools, between school staff and LSNA, and among schools and other institutions in the community.

|

Creating

Schools as Centers of Community

(an excerpt from “The Whisper of Revolution: Logan Square Schools as

Centers of Change”)

Another resolution of the Holistic Plan came from

LSNA's and the school's fight for the school annexes. In a neighborhood with

very few public spaces, it seemed a crime that the schools sat empty 75% of the

time. So when the annexes were built, it was with the idea that they would

become community centers outside of regular school hours. This idea was also

incorporated into the Holistic Plan and was met so enthusiastically that even

schools that didn't have the new annexes, such as Brentano, were on board for

creating new community centers.

Many of the parent mentors had set personal goals

around obtaining their GEDs or learning English. However, they were finding it

very difficult to achieve their goals. Places that offered GED classes were

too far to walk to or entailed complicated public transportation routes;

childcare wasn't offered, or was an additional charge, or had a mile-long waiting

list. A group of seven Funston parent mentors dreamed of having adult

education classes right in their school, with convenient hours and free

childcare. The Logan Square Neighborhood Association was right there with

them. Coming from a community organizing rather than a social service

perspective, they realized that in order to create a successful community

center with programs that people really wanted to attend, they had to find out

what people in the neighborhood really wanted. They began knocking on people's

doors. They talked to people about their goals, their needs, and their

obstacles. They learned a lot about the neighborhood and the people who shaped

it. "It was a life-changing experience

for me," says Funston parent and community center coordinator

Ada Ayala.

Ayala and the

other parents were true to their goals. After talking to about 700 people in

the neighborhood and in the school, they set out to find free programs that

would address the top priorities named in the survey: GED classes in English

and Spanish, English as a Second Language classes, and affordable childcare.

Another concern that was brought out in the interviews and surveys was the need

for security in and around the building so people would feel secure going there

at night. The group had a shoestring budget for security and childcare but did

not have money for classes. They negotiated with Malcolm X College for over

six months and finally managed to bring in the classes for free. |

The importance of building relationships is especially evident as parents begin to develop trusting relationships with each other and with school staff. These relationships lead to increased parent engagement in the life of schools, which often leads to involvement with other community issues through participation in LSNA. Trust is also evident in the relationships that school principals in Logan Square have developed with LSNA and with each other through LSNA's principals group meetings. In this section, we begin by looking at new relationships of trust developed among community members as they become involved with the Parent Teacher Mentor Program and the Community Learning Centers. We then look at enhanced levels of communication between parents and teachers. We conclude by looking at new networks that link LSNA schools to each other and to other organizations in the neighborhood and city.

Building on the relationships developed during the campaign against overcrowding, LSNA organizers have also continued to bring LSNA principals together for quarterly meetings. These meetings provide an unusual opportunity for principals to share problems and strategies with each other, as well as providing a forum for developing new initiatives. According to one principal, "There's a level of trust that we can be honest. …We realize we're all in the same boat." Another explains,

We talk about what was successful, what wasn’t successful from a previous year. And then maybe we talk about some new ideas, some new initiatives that are coming out.…We didn’t do this before LSNA got us together.

This group provides an opportunity for principals to collaborate on implementing their schools' Parent Teacher Mentor Programs and Community Learning Centers.

One initiative endorsed by the principals' group is a yearly neighborhood-wide reading celebration, which serves as a year-end culmination to the Links to Literacy campaigns used in the schools. Links to Literacy encourages students across all the LSNA schools to read more and LSNA has brought together the Links’ coordinators from 12 schools and the local library to exchange ideas and plan a joint outdoor celebration as a reward for the best 600 readers. Students in the participating schools read more than 150,000 books last year.

In addition to valuing the partnership among schools that is promoted by LSNA, principals also value the support of LSNA itself. As one principal told us,

It was absolutely mandatory that they were there for us because we could not possibly have done [these programs] on our own.…Having someone who functions outside the system actually helps bring resources.

As the schools became more involved with LSNA through developing the Holistic Plan, developing new school/community programs, and participating in other LSNA organizational activities, other community institutions also became interested in supporting the schools. One major connection has been with community banks, which decided that they wanted to identify a way that their programs could also enhance the Logan Square schools. Out of this, a special homeownership program for teachers was developed, which facilitated homeownership in Logan Square for teachers in the schools. Pastors also supported the schools through working with parent mentors on creating and implementing a Character Education program in the public schools. The YMCA and the local park also work with the Ames Middle School and the Ames Community Center to coordinate recreation, social services, and cultural activities. Like the relationships between the banks and the schools, the relationships between other organizations and the schools were mediated through shared participation in LSNA.

Both parent mentors and school staff have described the dramatic personal transformation and newfound sense of trust and sense of connection for parents who participate in parent mentor training or do outreach for community centers (for the story of how LSNA started these programs, please see the box “Creating Schools as Centers of Community” on 30). The programs create "bonding social capital" (relationships of trust among people who are similar in terms of race, class, ethnicity, or social roles).

Typically the parents most involved in LSNA's programs are low-income women who have not been actively involved in their children's schools, in neighborhood organizations, or in the formal job market. Over and over, in interviews, focus groups, and public presentations, we heard stories of social isolation and lack of personal direction, as exemplified in the words of Isabel, a Puerto Rican who grew up on the mainland and attended college for a time.

I used to be one of those moms who just dropped their kids off at the school, but the first week we had the Parent Mentor training program it opened my eyes a lot, because you are so used to thinking about your kids, the house and everybody else, that you are never thinking about yourself.

Many of the parent mentor participants are either recent immigrants who don’t speak English or women who have limited social contacts outside of their kinship networks. U.S.-born women, as well as immigrants from Latin America, vividly described how they learned new ways of connecting with other adults as well as with their own children through their participation in the Parent Teacher Mentor Program. Isabel, who is now a parent organizer for the program, told us,

The program is great because it changes a lot of people's lives. Not only for myself, but when other mothers first get into the program, their self-esteem and everything is so low. When they first started, they were like really quiet; they would keep to themselves. And now you can't get them to shut up sometimes. I mean you see the complete difference, they really change their life. They are more outgoing. They are willing to do more for their kids. It's like night and day, they're so different.

Another mother described a similar experience of connection with the larger community while working with students, teachers, and other parents on outreach for the new Ames Community Learning Center.

The Community Center has made us. I have been married for 15 years and I had never had a job. In the beginning, I had some problems with my husband because he didn't want me to go out. And I told him, really–what I need is to go out, to know, to talk. And here I learned to talk because before my world was my daughter and my husband. And now I feel different. I'm a different person.

|

Shy No More I remember a child that started in first grade. This child did not know how to write his name so they assigned him to me. I worked with him for three months. Within those three months this child learned how to write and read. The teacher told me that this was a miracle. Working with students has been very rewarding for me. It has also helped me help my son in his schoolwork. What have all these experiences done for me? Well, let me tell you. I was a very shy person. I was afraid to talk to other people. I was always in the house. I did not go anywhere but to take my son to school. Becoming a Parent Mentor has helped me to socialize with other people. It has helped me to become involved with the school and with the community. It has helped me build up my self-esteem. I was able to go to school and study to get my G.E.D. Now I am studying Bilingual Education. Before, I didn’t have the courage to do any of these things. Ya no soy tímida Recuerdo a un alumno que iniciaba el primer grado. Como no sabía escribir su nombre me lo asignaron a mí. Trabajé con el durante tres meses y en ese tiempo aprendió a leer y escribir. La maestra me dijo que era un milagro. Para mí ha sido muy grato trabajar con los estudiantes. Me siento muy especial cuando me brindan su confianza. Adamás, el trabajo me ha preparado para ayudarle a mi hijo con sus tareas, lo cual ha significado mucho para él. Quiero contarles lo que estas experiencias me han brindado. Yo antes era una persona muy tímida. Tenía miedo de hablar con la gente y me quedaba siempre en mi casa. No salía más que para llevar a mi hijo a la escuela. El trabajo como Padre Mentor me ha ayudado a tener una vida social y conocer a otra gente. Me ha ayudado a involucrarme en la escuela y en la comunidad. Me ha ayudado a mejorar mi autoestima. Fui a la escuela y estudié para sacar mi preparatoria. Ahora estoy estudiando educación bilingüe. Antes no tenía el valor para hacer todas estas cosas. Conchita Perez |

The coordinator of the Funston Community Center also described the creation of new relationships among parents:

The fact that parents have more roles in the school is important. We communicate a lot among ourselves. The parents know and support one another more. So, for example, if one parent cannot pick up her child, then that parent calls another parent to do it and it is done. I have also seen parents wanting to work for other parents. They are more interested in the Center and how everyone is developing their skills…When the Center first started, I thought it will not last because the community was not going to respond. And I was wrong. We have seen an overwhelming response from the community.

Enhanced Communication between Parents, Teachers, and Students

Improved relationships between parents and teachers, known as “bridging social capital,”[12]are another result of school/community partnerships in Logan Square classrooms. This evolving sense of trust is critical for schools in low-income communities and communities of color where parents and school staff tend to blame each other for children's lack of progress.

The presence of parents in the schools also creates new kinds of relationships between adults and children in classrooms, contributing to more constructive student engagement with their classes and subject matter. According to one parent,

To me being a parent mentor means being able to communicate with the students as well as the teachers. And when you're able to share some of the things that you know about the subjects, it seems to bring out a lot of good in a kid. I've noticed that in certain classrooms that I go to, the kids, they want to participate even more, even the ones that weren't even really doing well. The teachers notice how well they're making progress because they're interested, and I keep their interest going.

As parents work closely with teachers, they develop an understanding of what actually happens in the classrooms and learn how they can help their own children.

This leads to increased parent involvement with homework, in reading to their children, and in leading activities such as Family Math and Family Literacy. Having parents in the classrooms through the Parent Teacher Mentor Program also creates a more intimate environment for students, which is reflected in a decrease in discipline referrals.

Parent mentors universally attest that working directly with teachers helps them understand how important it is to support the teachers and help their own children meet the requirements for success in school. As one parent said,

Being here has helped me work more with my children. I pay attention to the work that is assigned to them. I know how they work and how to help them improve.”

During focus groups conducted during the Winter of 2002, parents told us that the skills that they learned by watching teachers translated immediately into skills that they could use with their own children, such as asking questions, playing more games, and becoming more patient.

|

“Este trabajo

es para tí” En mi vida han pasado muchas cosas, pero hubo un acontecimiento que ha sido muy importante para mí. Ocurrió en octubre de 1999 cuando mi niño llegó a mi hogar con una aplicación para el programa de Padres Mentores. Yo pensaba que era encapáz de realizar este tipo de trabajo, pero mi hijo me dijo, “Mami, este trabajo es para tí.” Bueno, pues me decidí a tomarlo y en noviembre del mismo año commencé a trabajar como Padre Mentor en la Escuela Mozart. En ese momento comprendí que nada es imposible cuando estamos dispuestos a lograrlo. Ahora me siento realizada como madre, como ser humano…He vivido muchas experiencias en el salón de clases, pero sobre todo la confianza que los niños me han demostrado me llena de mucha satisfacción…Eso me llena de orgullo porque veo qui mi esfuerzo está dando fruto. “This Job Is for You” Many things have happened in my life, but there one event has been very important for me. It happened in October 1999, when my child arrived from school with an application for the Parent Mentor program. I thought that I was incapable of carrying out a job like that, but my son said to me, “Mami, this job is for you.” So I decided to go ahead and take it, and in November of that same year I began working as a Parent Mentor at Mozart School. That is when I learned that nothing is impossible when we are determined to achieve it. Now I feel fulfilled as a mother and as a human being…I have had many experiences in the classroom. The thing that gives me the most satisfaction is the trust that the children place in me…That makes me very proud because I see that my efforts are bearing fruit. Marisol Torres |

Parents' respect for teachers increases as they see the challenges of teaching in the overcrowded Chicago schools. According to one parent mentor,

At first I was so nervous and did not really trust the teachers, but all that changed once I worked in the classroom. Now we trust each other. At first, I thought that teachers did not do their work or that they really did not want to work with children. Once I started to work here, I have learned that the teachers work a lot and that with so many children in the classroom it is very difficult to work alone.

From the teachers' perspective, parents become valued partners in the classrooms. As one teacher says,

At this school, we have seen [the Parent Teacher Mentor Program] work very well. Those teachers who have parents in the classroom do not get tired of praising them. They really see them as essential to their teaching…And believe me, teachers who have parent mentors in their classes see them as more than a mentee. They see them as partners and friends.

One teacher explained,

Before, parents were seen as disciplinarians at home and teachers were the educators at the school. Now parents are seen as partners in educating the children in the school and in the home.

According to another teacher, “When I came here [7 years ago], I don't remember seeing that many parents in the programs. Now it's parents everywhere."

According to some parents, as teachers become accustomed to having parents in the school as parent mentors, the overall respect for parents increases. According to one,

Now teachers have a need for parents in their classrooms. Before teachers did not want a parent in their room working with them. Maybe teachers thought the parents did not have the ability to work in the classroom and now they have seen that parents can.

The LSNA Education Committee's “Respect for Children” campaign, (previously mentioned in this chapter's sub-section on sustained campaigns), shows that LSNA is continuing to work with teachers and schools to fully develop a culture that respects the class, language, and cultural attributes of students in urban schools in low-income neighborhoods.

LSNA’s Lead Education Organizer, Joanna Brown, wrote the following narrative that tells what happened when the parents on LSNA's Education Committee met with principals during the winter of 2001,

One by one the principals responded to the question: “What do you do if you find out a teacher is speaking inappropriately to students?” The committee felt the meeting was useful, although one principal called LSNA and said, “We need to find better answers.” One concrete suggestion that came out of the discussion was a joint parent/teacher professional development session on creating a positive climate for learning.

Eighty people, about half teachers and half parents, attended the Saturday morning workshop at a local hotel. After being served a lovely breakfast, they were asked to leave the room. When they returned, the tables had been pushed to the wall and they couldn’t find their belongings. “Hurry up, hurry up, you’re late,” yelled presenter Elena Diaz, a Mexican educator and actress. A principal who attended described how some teachers, insulted, were ready to walk out, until they realized they were being asked to experience being a second grader on a day their teacher is frustrated about something.

In the fall of 2002, the Education Committee hired Elena to work with both parents and teachers about issues of positive discipline and teaching and learning. She has conducted workshops that opened discussion of school climate and the classroom physical environment; teachers began to communicate their deep frustrations but gradually began to give each other support; mothers practiced dramatized reading, learned to become more sensitive to the impact of their voices and body language on children.

One group of six mothers with whom Elena worked developed a skit called “Supermama,” which they then performed for other mothers in the Bilingual Committee meetings of neighborhood schools. The heroine is busy cooking, cleaning, ironing and generally taking care of her husband and children. The teacher calls her in for a meeting because her child is not doing his homework. As responsibilities pile up, she becomes more and more frustrated, until in comes….Supermama! There is song and a dance and then the audience tries to help the mother with their suggestions – she must teach her children to help, her husband should help, she needs time and space for herself, a vacation…. It ends on a positive note.

In this document Joanna reflected,

We are trying to build respect through practice. In a sense, all our work is about “respect.” As teachers and parents work together, they learn to respect each other. We—and I mean all of us, organizers, teachers, parents, principals—are working to change the culture of urban schools, to value families and what they know, making school a more and more positive, affirming experience for the children. This is not a quick or simple task. It means no less than changing the paradigm of schooling.

As LSNA works to change the culture of schools, it also has fostered the growth of a network that links the local schools to each other and to other local and citywide organizations. Relationships among the participating schools make possible the ongoing creation and implementation of LSNA's school-based programs on a neighborhood-wide basis. For example, lead teachers in charge of the Parent Mentor program in each of the seven schools have met monthly with LSNA since 1996.

Opportunities for leadership and leadership development characterize all aspects of LSNA's work in schools. One aspect of leadership development in LSNA consists of the extensive opportunities for individual and family empowerment within LSNA's programs. A second aspect of leadership development is LSNA's work in identifying and training parents and community members to take on leadership roles within the schools and LSNA.

At a meeting held in the fall of 2000, Research for Action asked members of the LSNA Education Committee how they saw the connection between personal empowerment and community change. According to one mother, who is now on Local School Councils in three schools which her children attend:

When we get parents participating, it increases their self-esteem. They were very timid. Now they have more self-confidence after participating in the programs. They come out of the programs with much more self-esteem. Many of the people who were in the parent mentor program, they didn’t leave their houses and now, they’re ahead of me, they’re driving.

Another mother who now works on LSNA's outreach committee told us,

There are people who are working in the office on the issue of real estate taxes. They’re dealing with the taxes, and they’re working on outreach. All this came out of the parent mentor program. And it started with the schools, but it moved. Change for the children. Personal change. Change for all. But it all came from the parent mentor program.

A third agreed:

When I became a parent mentor many years ago, I was one of those people who were very shy, but after 3 or 4 years, it ended up that I am doing many more things. For me it was a very large experience, to participate in the school. I am still a baby in LSNA, but the most important thing is to get involved. I am learning a lot from my own experience. I'm not only involved in LSNA, I'm involved in the school: in the council… as president of a committee…and I like it.

Individual and Family Empowerment

All parent mentors set personal goals for themselves as part of their participation in the program. Often these include getting a GED, learning English, getting a job, or attending college. Most of the 840 parent mentor graduates over the years have gone on to job training programs, adult education classes, volunteer activities, or leadership roles in the school. Most of the teaching assistants and other paraprofessionals hired in LSNA schools in the past several years have been parent mentor graduates. As discussed above, parents consistently tell a story of personal transformation through their involvement in the Parent Teacher Mentor Program.

As the teacher who coordinated the program at one school explained,

The parent organizer does all things to have well-informed parents in the school. She works with them in all areas—political, emotional, economic."

The assistant principal at the same school commented, “I just can't tell you what a difference it has made in the lives of our parents.”

LSNA’s Community Learning Centers create a safe and accessible environment for entire families to participate in educational and recreational programs. The centers offer a variety of programs determined locally, including homework assistance, adult education, cultural programming, and family counseling, after school and in the evenings. The first center to open, Funston, graduates approximately fifty Spanish GED students a year. LSNA has the highest graduation rate for Spanish GED of all off-campus programs run by the Chicago City Colleges.

In 2000, LSNA also partnered with Chicago State University to offer full scholarships and a bilingual teacher certification program for forty-five parent mentors, teacher aides, and other Logan Square community members. Classes are held in one of LSNA’s community centers, and the program was funded by a grant proposal written jointly by LSNA and Chicago State.

We went looking for a program like this because so many of the parent mentors just did not want to leave the schools. They had the teaching bug. So many had stories of how they had changed some child’s life, gotten them interested in school for the first time, taught them to read. They didn’t want to go back home, or to a factory, to a clerical job, or to clean houses. They wanted to teach. They decided to call their program, ‘Nueva Generacion,’ or New Generation. They bonded closely as a cohort. It’s a difficult program, and everyone has busy lives, but they don’t let each other drop out.. Two and a half years into the program, 41 of the students are still enrolled, a remarkable retention rate. [Joanna Brown, 2002]

This is an important extension of LSNA's work with parents, many of whom see the bilingual teacher certification program as an opportunity to extend their skills, interests, and commitment to improving the educational experience of Latino children that they first identified when they were parent mentors. LSNA is looking for ways to start a second cohort and to promote this as a successful model for teacher preparation that would provide committed teachers for low-income neighborhoods.

| Number of Parent Mentors, Spring 2001: n=114 |

| 75% of parent mentors are immigrants |

| 44% have GEDs or high school degrees (US or foreign) |

| 23% are in ESL classes |

| 22% are in GED classes |

| 10% are enrolled in college classes |

Often the first leadership role that parents take on in the school is around safety issues. Parents in all the schools have formed patrols to ensure safety around the perimeter of the schools. Parent mentors have been a major source for volunteers for the schools’ safety patrols and played important roles in organizing many of them. Other safety issues that parents have taken on include getting rid of prostitution around one school, closing down drug houses near schools, organizing neighbors to stay outside while children are going to and from school, and organizing campaigns for traffic safety.

Parent mentor graduates commonly take leadership roles on LSCs and other legally-mandated committees such as the bilingual and principal selection committees. LSNA is active in recruiting and training parents for LSCs; LSNA schools typically have full slates or contested elections and high levels of voter turnout compared with the turnout at many other schools in Chicago. For example, in the last two elections one LSNA school had the highest number of LSC contestants in its region. Parent mentor graduates have been instrumental in conducting community surveys to help get new community centers started. They also staff community centers and participate on the governing bodies of LSNA's six school-based community centers. In addition, parent mentor graduates and other LSNA leaders coordinate many literacy activities at their schools, including reading with children, conducting library card drives, and creating lending libraries for parents. Principals and parent organizers consistently report that parent mentors and parent mentor graduates form the majority of active parents in their schools.

As parents become involved in their schools, they seek out new ways to remain active and build their leadership skills. An organizer’s written reports tell how this happened at one school.

At Mozart, the parents who surveyed residents for the Community Learning Center planning process came back from door-knocking excited, energized, frustrated, and with many stories to tell. Angry homeowners had complained of dirty alleys, disorderly empty lots, and unruly teens. Old ladies had invited them in for tea and unburdened themselves of their life stories. Strangers had offered to share their knowledge in the community center. Out of many such demands for reconnection, the idea of block organizing was reborn. (Joanna Brown, LSNA report to MacArthur, 1999)

About ten women who participated in the CLC survey developed into a paid block club organizing team which still exists, though new members have been added as old ones got jobs or moved. This “Outreach Team” spent the first two years organizing block clubs and working on block issues (safety, rats) in the Mozart area. More recently, they have worked for LSNA on a variety of issues more widely in the neighborhood —passing out flyers for real estate tax workshops and zoning meetings, collecting 5,000 signatures on a petition for an immigration amnesty and 2,200 signatures for a campaign to expand family health insurance to low-income families. Most recently, they have become an expert team in signing up uninsured families for state-provided children’s health insurance and low-cost non-profit clinics. (Joanna Brown, manuscript for the MacArthur Documentation Project, 2001)

LSNA’s involvement in neighborhood schools provides an important setting for the growth of community leaders. During the period of RFA's research, we have observed a new set of education leaders, following in the footsteps of a former generation of parent leaders who led the struggle for new buildings and brought the Parent Teacher Mentor Programs and Community Learning Centers to their schools. Many of the earlier education leaders are still involved with LSNA, but now have staff positions with LSNA or other community organizations.

Mildred Reyes, a key leader in the fight for Ames School and now an LSNA health organizer, described her evolution as a leader in the Mozart School. She began coming into the school because she wanted to help with her daughter, who was in a special education class. The LSC president, who was also the chair of LSNA's Education Committee, “saw me there everyday and pulled me into more activities,” she explained. “I ran for the LSC because I wanted more money for special education. We had to fight for it.” Mildred worked with LSNA leaders and organizers to develop her skills in chairing meetings, speaking in public, analyzing school budgets, and advocating for special education services. She told us, “We brought in a nurse and three therapists. I also learned that the teachers have to take workshops in Special Ed.”

Mildred continued her involvement, working closely with the principal, other parents, and the school/ community coordinator on a wide range of activities, including instituting the Parent Teacher Mentor Program, securing funding for a lending library for parents, doing outreach for a community center, and continuing to advocate for students. Like many other parents who are active in their schools, Mildred has also become a leader within LSNA.

Rose Becerra, a participant in Brentano school’s first parent mentor program in 1996, ran the Brentano parent mentor program and is now an LSNA housing organizer. She describes how her involvement with the parent mentors motivated her to organize around housing issues.

The one [story] that makes me feel really bad, and it might not mean anything [but] I had 6 parent mentors living in one apartment building (it was a 17 unit building) and they got a 30 day notice and they were offered $2000 to be out in 5 days. These people started construction even before the 30 days were up. There were no permits issued, nothing. They were just told to leave. And not one of those families came back to Brentano. So we lost 17. I lost all those parent mentors. I lost a few friends. The fact they were able to do this; they weren’t issued any permits and when they were they were back-dated. To me, I look at the parent mentors we lost, the children we have lost from the school, the rental units we lost, and the lack of aldermen caring about those people; and even back-dating the permits! That all ties into what we’re up against.

Because building power, creating relationships, and developing leadership are central to the organization, LSNA's school-based programs are very different than those of traditional social-service agencies within schools. Structures and processes for democratic participation are essential for ensuring that LSNA's school-based programs are responsive to the needs of the community. In addition, the democratic structures and processes within LSNA allow parent leaders who emerge through LSNA’s work in schools to have input into the direction of the organization as a whole.

As spelled out in our overview of LSNA, organizational priorities are identified by issue committees, the Executive Board, and the Core Committee. Leadership by low- and moderate-income residents, as well as involvement of middle-class community residents and professionals who work in local institutions, is evident on all of these key governing bodies. Parents from LSNA schools play strong leadership roles in all of these arenas. The democratic structures within LSNA provide vital opportunities for discussions of differences, as well as development of collaborative relationships and shared agendas, across the different groups which make up Logan Square. One illustration of this kind of democratic participation within LSNA is the previously described situation in which parents on the LSNA education committee identified "respect for children" in LSNA schools as an ongoing concern. Reaching out to teachers and principals, the committee implemented a campaign to keep exploring this and other challenging issues related to teaching and learning in Logan Square schools.

Community advisory boards established for LSNA's community centers are also important democratic structures that mediate the different interests of parents, classroom teachers, and school principals. Each advisory board includes community center teachers, community center students, and other community representatives. It also includes classroom teachers and the school principal. At the time that RFA began our research, LSNA organizers expressed concern that community centers were losing their vitality and connection to neighborhood needs due to school staff's hesitation to share space with community members. Rather than develop new programs in response to articulated concerns, the regular school staff would have been content to continue to offer classes like GED and ESL that had already been very successful.

During this period, LSNA, as part of the participatory research for this study, conducted new surveys of community needs, trained community center staff in organizing techniques to encourage leadership development among community members, and trained the advisory boards in how to develop relationships with the daytime staff. By the end of RFA's research, community members on the advisory boards were using survey data to advocate for new programming, including children's activities and cultural activities. Community members on the advisory boards have successfully advocated for community needs and new programs while maintaining and strengthening their relationships with school staff. For example, community center boards have asked for more activities for the community, but have also initiated special events to recognize and thank regular classroom teachers for sharing their rooms and resources with the evening students.

LSNA's democratic processes and structures also create arenas in which low-income parents in LSNA schools are able to identify and act on community issues which have not been previously identified by the organization, and which may not have been identified by more middle-class members of the Logan Square community. During the past two years, former parent mentors, with the support of organizers, initiated two new committees and issue areas within the Holistic Plan: immigration and health care. When a group of former parent mentors expressed an interest in immigrant rights, the organizer encouraged them to meet with local pastors and arranged to provide information and workshops about immigrant rights and upcoming changes in immigration law to their congregations. Based on the success of this effort, the same group of women wrote and presented a proposal to the Core Committee for a new immigration committee; the immigration resolution was approved for inclusion in the Holistic Plan. Similarly, the following year, through opportunities identified by an LSNA organizer, LSNA’s Outreach Team, composed of current and former parent mentors, began working with a statewide campaign for increasing health care to the uninsured and then wrote and presented a health care resolution to the Core Committee.

In this chapter, we have examined how LSNA's relational approach to grassroots organizing plays out and builds community capacity in the organization's work with schools. Beginning with the lens of power and policy, we demonstrated that LSNA mobilized the community in a sustained and successful campaign for new school facilities. Based on the power LSNA demonstrated during the campaign against overcrowding and on the relationships built with schools during the same campaign, LSNA was able to develop a school/community partnership based on mutual trust and respect.

Using the lens of relationship building, we looked at the relationships developed through the school/ community partnership and the programs developed through this partnership. LSNA's parent mentor program and Community Learning Centers foster new relationships of trust among community members and between parents and school staff. Looking at leadership development, we see that parents, especially mothers, who are involved with LSNA programs, make a strong connection between personal empowerment and community leadership.

The democratic processes and structures of LSNA are key to maintaining relationships across different constituencies within Logan Square and maintaining the organization's ability to focus on the needs of low- and moderate-income community members, while creating relationships that cross over boundaries of class and status.

The relationship between LSNA's work in schools and its evolving campaign to maintain affordable housing in the neighborhood is particularly important to understand. Through its school/community partnerships, LSNA developed programs that reach out to poor and moderate-income residents of Logan Square, groups who feel that they are being pushed out of the neighborhood. LSNA's school/community partnership has produced a strong base of leaders from the same constituency. At the same time, the success of its programs has built LSNA's visibility and legitimacy within the neighborhood and the city. Together, these factors provide a strong commitment within LSNA to support affordable housing.